Overview – Applied Ethics

Applied ethics takes the ethical theories we studied previously and applies them to practical moral issues. You may also be asked to apply metaethical theories to these issues.

The syllabus looks at 4 possible ethical applications:

Stealing

It’s pretty obvious what stealing is. But to frame it in a philosophical way, people often say that individuals have property rights – i.e. that they have rights over certain things. To steal is to violate these property rights.

Utilitarianism

For act utilitarianism, whether or not it is acceptable to steal something will depend on the situation. There is no moral right to property over and above its utilitarian benefits and so if an act of stealing results in a greater good then it would be morally acceptable to steal.

For example, act utilitarianism would say it is acceptable for a starving person to steal food if it saves their life, because the victim’s loss is outweighed by the thief’s benefit. Similarly, an act utilitarian could argue that it’s morally acceptable for very poor people to steal from very rich people (like Robin Hood), because the rich person’s loss is insignificant compared to the thief’s gain.

For example, act utilitarianism would say it is acceptable for a starving person to steal food if it saves their life, because the victim’s loss is outweighed by the thief’s benefit. Similarly, an act utilitarian could argue that it’s morally acceptable for very poor people to steal from very rich people (like Robin Hood), because the rich person’s loss is insignificant compared to the thief’s gain.

However, rule utilitarianism could argue that although there may be individual instances where stealing leads to greater happiness, having a rule of “don’t steal” leads to greater happiness overall. John Stuart Mill (the rule utilitarian person) makes a similar argument in his discussion of justice and property rights.

For example, a society that permitted stealing would be one in which no one could trust anyone. Everyone would live in constant fear of being robbed by someone who had convinced himself that stealing from them would lead to greater happiness. This distrust and fear would lead to a less happy society than one in which stealing isn’t allowed, and so a rule utilitarian could argue that we should follow the “don’t steal” rule.

In short: Depends on act/rule. Act would say stealing is sometimes morally acceptable (depending on the specifics of the situation). Rule may say stealing is always wrong.

Kant’s deontological ethics

Kant would argue that a maxim/rule that allowed stealing would fail the first test of the categorical imperative because it would lead to a contradiction in conception:

- The categorical imperative says: “act only according to maxims you can will would become a universal law“

- My maxim is: “I want to steal this thing”

- If I will stealing to be a universal law, then anyone could steal whenever they wanted

- But if anyone could steal whenever they wanted, the very concept of personal property wouldn’t exist (because if anyone is entitled to just take my property from me in what sense is it mine?)

- And if there is no such thing as personal property, the very concept of stealing doesn’t make sense (because you can’t steal something from someone if it isn’t theirs to begin with)

- Therefore, willing that “I want to steal this thing” leads to a contradiction in conception

- Therefore, stealing violates the categorical imperative

- Therefore, stealing is wrong

In short: Stealing is always wrong: It leads to a contradiction in conception and violates the humanity formula.

Aristotle’s virtue theory

Aristotle says there are some actions that never fall within the golden mean – and stealing is one of them. According to Aristotle, stealing is an injustice because it deprives a person what is justly and fairly theirs.

Even in extreme cases, such as stealing £1 from a billionaire to buy bread to save a starving child who will otherwise die, Aristotle would still likely say that stealing is wrong.

The reason for this is that Aristotle distinguishes between unjust actions and unjust states of affairs. A starving child may very well be an unjust state of affairs – an unfortunate situation – but that’s just the way the world is sometimes. According to Aristotle, it is much worse to deliberately and freely choose to commit unjust actions – even if you are committing these unjust actions to counteract unjust states of affairs.

In short: Aristotle seems to say stealing is always wrong. But virtue ethics (more generally) could argue that stealing may fall within the golden mean in extreme circumstances (e.g. to avoid starving to death).

Metaethics

- Moral realism:

- Naturalism: “Stealing is wrong” is true if stealing has the natural property of wrongness (e.g. because it causes sadness, and sadness is a natural property)

- Non-naturalism: “Stealing is wrong” is true if stealing has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Moral anti-realism:

- Error theory: “Stealing is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Non-cognitivism:

- Emotivism: “Stealing is wrong” just means “Boo! Stealing!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Stealing is wrong” means “Don’t steal!” and so is not capable of being true or false

Simulated killing

Simulated killing is about fictional death and murder, such as in video games and films. It’s not about actually killing people (which is more obviously wrong).

This might seem like a non-issue at first – how can just watching or pretending to kill someone be bad? But there are all sorts of moral dimensions you can discuss. For example:

- The difference between watching a killing (e.g. in a film) and playing the role of the killer (e.g. in a video game)

- The effects simulated killing has on a person’s character (e.g. whether exposure to simulated killing makes them more violent)

- Whether simulated killing is wrong in itself (in the UK, for example, video games involving rape and paedophilia are illegal even though they’re just simulations – why not murder too?)

Utilitarianism

The obvious response of act utilitarianism would be that simulated killing is morally acceptable. After all, the person watching the film or playing the video game gets some enjoyment from the simulated killing, and the person being killed doesn’t actually suffer because it’s only fictional. In this situation, simulated killing results in a net gain of happiness.

But from a wider perspective, there are ways simulated killing could possibly decrease happiness. For example, if exposure to simulated killing makes a person more likely to kill someone for real, then maybe this pain would outweigh the happiness? Maybe simulated killing makes people more violent in general?

There are all sorts of studies on this topic, often with conflicting conclusions. If nothing else, these considerations support the difficult to apply objection to utilitarianism. However, if there was an obvious and irrefutable study that showed simulated killing makes people significantly more likely to murder in real life, then rule utilitarianism could say simulated killing is wrong.

In short: Utilitarianism would mostly be fine with simulated killing. Act utilitarianism would say there is no actual suffering involved, only the pleasure of the person engaging in the simulation. Rule could potentially argue simulated killing is wrong, but would have to make the case that it leads to less pleasure overall.

Kant’s deontological ethics

Kant would most likely have no major objection to simulated killing. Murdering people in video games does not lead to a contradiction in conception, or a contradiction in will, or violate the humanity formula. In other words, simulated killing does not go against the categorical imperative.

However, Kant’s remarks on animal cruelty may be relevant here: He argues we have an imperfect duty to develop morally, which means cultivating feelings of compassion towards others. Simulated killing, like being cruel to animals, may weaken these feelings of compassion and so Kant could potentially argue we have a duty not to engage in simulated killing.

In short: Kant would probably be fine with simulated killing. However, although simulated killing does not directly violate any of our duties, Kant could potentially argue we have duties with regards to simulated killing (see Kant on animal cruelty for more).

Aristotle’s virtue theory

A key idea of Aristotle’s ethics is that virtue is a kind of practical wisdom (phronesis). According to Aristotle, being a good person is not just about knowing what the virtues are, it’s about acting on them until the virtues become habits.

So, Aristotle might argue that if someone spends a lot of time playing video games that involve simulated killing then they may develop bad habits (or at least not develop good habits/virtues). For example, repeatedly killing fictional innocent people in a game may make someone increasingly unkind or unjust.

On the other hand, Aristotle might argue that killing fictional people is not actually unjust or unkind. After all, they’re not real, and so there’s no real injustice. Doing unjust acts develops the vice of injustice, but simulated killing is technically not an unjust act. Also, Aristotle’s comments on tragedies – e.g. simulated killing in plays – might be relevant here: Watching plays (potentially involving simulated killing) can help cultivate appropriate emotional responses. For example, watching a courageous soldier act bravely in the face of death may provide moral insights and emotional engagement that encourages courageous character.

In short: Like with any application of Aristotle’s ethics, you have to consider the context – there are no ‘one size fits all’ rules. A virtuous person might partake in simulated killing in moderation as a form of entertainment and because they enjoy the competitive challenge of gaming. In that context, simulated killing might not be unvirtuous. But doing nothing with your life except killing people in video games just because you love killing people is almost definitely not virtuous.

Metaethics

- Moral realism:

- Naturalism: “Simulated killing is wrong” is true if simulated killing has the natural property of wrongness

- Non-naturalism: “Simulated killing is wrong” is true if simulated killing has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Moral anti-realism:

- Error theory: “Simulated killing is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Non-cognitivism:

- Emotivism: “Simulated killing is wrong” just means “Boo! Simulated killing!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Simulated killing is wrong” means “Don’t do simulated killing!” and so is not capable of being true or false

Eating animals

Utilitarianism

A conclusion of Bentham’s view that good = happiness is that utilitarian principles must be extended to animals (because animals can feel pleasure and pain just as humans can). Bentham says:

“The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being?”

– An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation

Peter Singer, another utilitarian philosopher, develops this line of thinking further. To privilege human pain and pleasure over animals is speciesist, he says (in a similar way to how privileging men over women, say, is sexist).

And so, since killing an animal to eat it likely causes more pain to the animal (and deprives it of future pleasures) than it causes pleasure for the human eating it, utilitarians would likely argue that eating animals is wrong.

There are, however, ways utilitarianism could potentially justify eating animals. For example, if you find an animal that’s already dead and eat that, then there’s no increase in pain. So eating animals in that situation would be acceptable.

Or you could argue that, if it wasn’t for farming animals for food, many animals would never have existed and so would never have been able to experience pleasure and pain in the first place. So, if the animals farmed for food have an overall happy life and a painless death, then eating animals is morally justifiable because it results in a net increase of pleasure. An implication of this view is that farming conditions and practices are important: Farming animals in cramped or uncomfortable conditions where they have unhappy lives, say, would be morally wrong according to utilitarianism.

In short: A straightforward interpretation of utilitarianism says eating animals is wrong because pain and pleasure are all that matter (regardless of species) and killing an animal to eat it causes more pain to the animal (and deprives it of future pleasures) than pleasure for the human eating it. But the answer differs depending on situation and different forms of utilitarianism may have different takes too.

Kant’s deontological ethics

Kant’s categorical imperative is only intended to apply to rational beings. Animals, Kant would say, do not have rational will and so are excluded from the categorical imperative.

Kant would say there is no contradiction in conception and no contradiction in will that results from the maxim “to eat animals”. And the humanity formula only says don’t treat humanity as a means to an end. Humans have a rational will and so are ends in themselves and should be treated as such. But animals, Kant would say, do not have a rational will and so can be treated solely as means. We thus do not have any duties towards animals.

However, Kant does argue that being cruel to animals violates a duty we have towards ourselves – the duty to develop morally:

“violent and cruel treatment of animals is far more intimately opposed to a human being’s duty to himself… and he has a duty to refrain from this; for it dulls his shared feeling of their suffering and so weakens and gradually uproots a natural predisposition that is very serviceable to morality”

– Metaphysics of Morals

According to Kant, Moral development involves developing compassion for other human beings but being cruel to animals weakens these feelings. So, even though we don’t have any duties directly towards animals, we do have duties in regards to them. As such, Kant might morally object to cruel farming practices but would not object to eating animals in principle.

In short: Eating animals is consistent with the categorical imperative and so is morally acceptable. We have no duties towards animals (though we need to be mindful of duties with regards to them).

Aristotle’s virtue theory

Aristotle’s discussion of eudaimonia is concerned with the good life for human beings specifically. Animals, unlike humans, are not capable of reason and so eudaimonia doesn’t apply to them. So, Aristotle would likely not see any issue with eating animals.

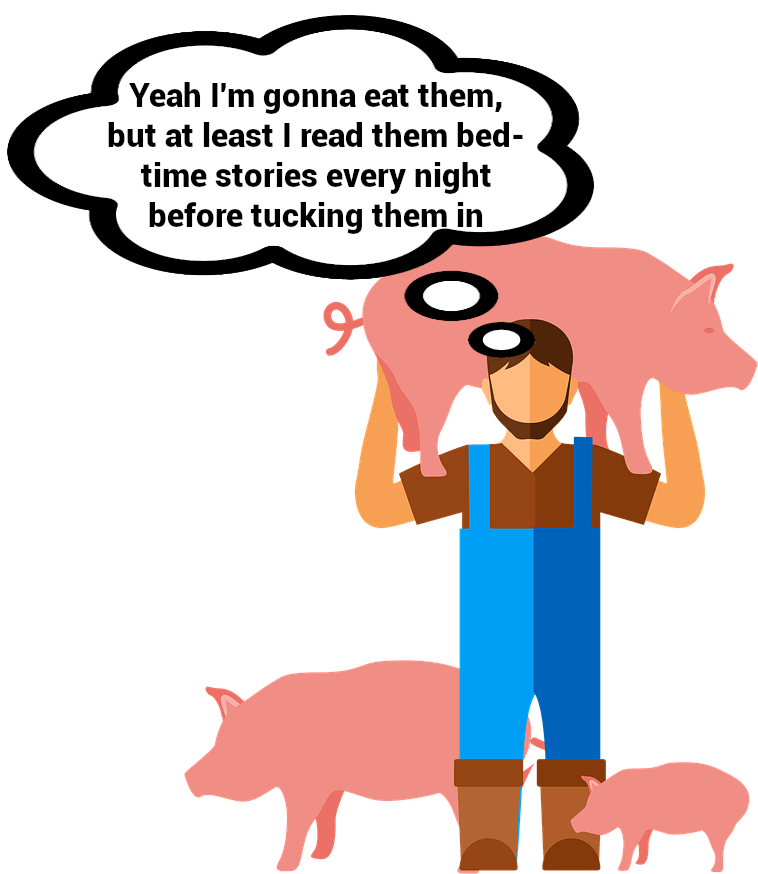

But some more recent virtue ethics philosophers take a different approach to this. Cora Diamond, for example, argues that eating animals is wrong – but acknowledges degrees to which different practices around eating animals are good or bad:

“To put it at its simplest by an example, a friend of mine raises his own pigs; they have quite a good life, and he shoots and butchers them with help from a neighbour… This is obviously in some ways very different from picking up one of the several billion chicken- breasts of 1978 America out of your supermarket freezer. So when I speak of eating animals I mean a lot of different cases, and what I say will apply to some more than others.”

– Eating Meat and Eating People

Diamond argues that animals are a different kind of being to humans and so we shouldn’t treat their happiness as equal (as Singer says above). However, animals are nevertheless living beings that can have good and bad lives. To completely ignore this, as some factory farming practices do, demonstrates the vices of callousness and selfishness. In contrast, rearing your own chickens and treating them humanely – even if you do ultimately eat them – demonstrates the virtues of sympathy and respect.

Diamond argues that animals are a different kind of being to humans and so we shouldn’t treat their happiness as equal (as Singer says above). However, animals are nevertheless living beings that can have good and bad lives. To completely ignore this, as some factory farming practices do, demonstrates the vices of callousness and selfishness. In contrast, rearing your own chickens and treating them humanely – even if you do ultimately eat them – demonstrates the virtues of sympathy and respect.

In short: Aristotle is fine with eating animals, as eudaimonia is about human flourishing and animals lack the rational soul that gives humans moral standing. But other virtue ethicists may take a different approach and argue that whether eating animals is acceptable depends on if it is done in the right way and for the right reason. Eating animals might sometimes fall within the golden mean, but not always.

Metaethics

- Moral realism:

- Naturalism: “Eating animals is wrong” is true if eating animals has the natural property of wrongness (e.g. because wrongness is a natural property such as pain)

- Non-naturalism: “Eating animals is wrong” is true if eating animals has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Moral anti-realism:

- Error theory: “Eating animals is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Non-cognitivism:

- Emotivism: “Eating animals is wrong” just means “Boo! Eating animals!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Eating animals is wrong” means “Don’t eat animals!” and so is not capable of being true or false

Telling lies

Utilitarianism

As always, whether or not act utilitarianism would say it’s morally acceptable to lie will depend on the situation. If telling a lie leads to greater happiness, then act utilitarianism would say you should lie. For example, if someone asks you whether they look good and they don’t, the utilitarian thing to do is to lie and say “yes”.

As always, whether or not act utilitarianism would say it’s morally acceptable to lie will depend on the situation. If telling a lie leads to greater happiness, then act utilitarianism would say you should lie. For example, if someone asks you whether they look good and they don’t, the utilitarian thing to do is to lie and say “yes”.

But rule utilitarianism could argue that a rule to “never lie” would lead to greater happiness than a rule that allows everyone to lie. For example, if everyone was an act utilitarian and always lied to increase happiness/reduce pain, then nobody could trust anything anyone said. And the rule utilitarian could argue that such a society – where no one can trust anyone else’s word – would be less happy overall.

In short: Depends on act/rule. Act would say lying is sometimes morally acceptable (depending on the specifics of the situation). Rule could potentially say lying is always wrong.

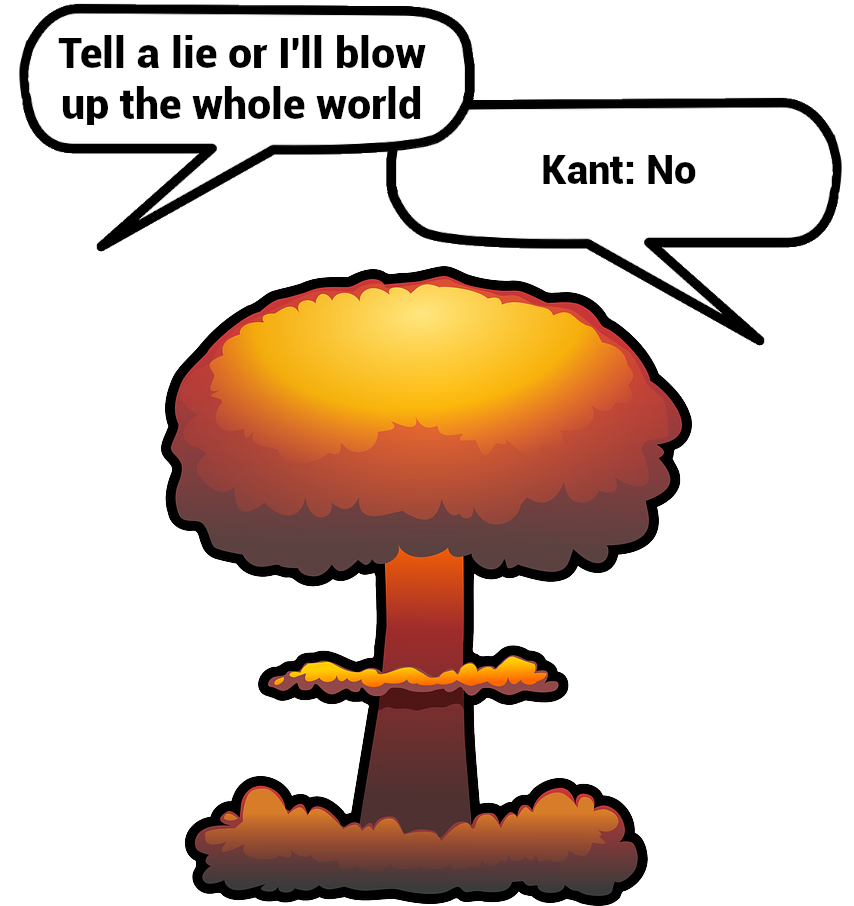

Kant’s deontological ethics

The point of telling a lie is to get the other person to believe something false. But if everyone always told lies, then people wouldn’t believe each other.

Given this, Kant would argue that the maxim “it’s OK to lie” fails the first test of the categorical imperative because it would lead to a contradiction in conception. If it was always acceptable to lie, the very concept of telling a lie (i.e. saying something is false in order to deceive someone into believing it’s true) wouldn’t make sense. So, according to the categorical imperative, we should always tell the truth – no exceptions.

Given this, Kant would argue that the maxim “it’s OK to lie” fails the first test of the categorical imperative because it would lead to a contradiction in conception. If it was always acceptable to lie, the very concept of telling a lie (i.e. saying something is false in order to deceive someone into believing it’s true) wouldn’t make sense. So, according to the categorical imperative, we should always tell the truth – no exceptions.

French philosopher Benjamin Constant challenged Kant’s approach of radical honesty by asking whether you should tell a known murderer the location of his victim when asked. Say, for example, a person is escaping an axe-murderer and you let them hide in your house. Shortly after, a crazy looking guy with an axe and blood-stained clothes asks you “where is he?” According to Kant, you should tell the truth: “He’s in here.” Telling the truth in this situation is seemingly the wrong thing to do, though, and so Kant’s ethics cannot be the correct account of moral action.

Kant’s response to this example is to stick to his guns: You should not lie to the murderer even to save a life. One reason for this is that Kant says the moral worth of actions is determined by whether they are done for the sake of duty, not their consequences. Further, in his essay on lying, Kant argues that it is impossible to know the consequences of our actions. But if we choose not to follow our duty and decide to lie, then we can be held responsible for the consequences. So say, for example, you lie and tell the axe murderer that “he’s next door” and, unbeknown to you the victim has sneaked out and really has gone next door, then you do bear some responsibility for the consequences of not following your duty.

In short: Lying is always wrong: It leads to a contradiction in conception and violates the humanity formula.

Aristotle’s virtue theory

In his discussion of the ‘social qualities’ of truth and falsehood, Aristotle says:

“Falsehood is in itself bad and reprehensible, while the truth is a fine and praiseworthy thing; accordingly, the sincere man, who holds the mean position, is praiseworthy, while both the deceivers are to be censured”

– The Nichomachean Ethics, Book IV.VII

Aristotle is talking about lying about oneself: On one side boasting is a vice of excess, and on the other false modesty is a vice of deficiency. Telling the truth – i.e. “the sincere man” – is in the middle (i.e. the golden mean) and so is the virtuous action.

When Aristotle says “falsehood is in itself bad”, he appears to be saying that lying is always wrong. However, Aristotle later describes degrees to which telling lies is bad: Lying to protect your reputation, for example, is not as bad as lying to gain money. Given this, you could potentially argue that there may be situations where it is morally acceptable to lie, such as in the example of saving a life above.

In short: There are quotes to suggest Aristotle thinks lying is always wrong. But considered in the context of the entire theory, Aristotle would more likely say lying can fall within the mean. When this is the case would, as always with virtue ethics, depend on context: e.g. white lies or extreme scenarios where a life is at stake.

Metaethics

- Moral realism:

- Naturalism: “Telling lies is wrong” is true if telling lies has the natural property of wrongness

- Non-naturalism: “Telling lies is wrong” is true if telling lies has the non-natural property of wrongness

- Moral anti-realism:

- Error theory: “Telling lies is wrong” is false because the property of wrongness doesn’t exist

- Non-cognitivism:

- Emotivism: “Telling lies is wrong” just means “Boo! Telling lies!” and so is not capable of being true or false

- Prescriptivism: “Telling lies is wrong” means “Don’t tell lies!” and so is not capable of being true or false