Overview – Ethical Theories

Ethics is the study of morality – i.e. right and wrong, good and bad.

The syllabus looks at 3 ethical theories:

Each theory provides a framework intended to guide moral behaviour. We can apply these theories to ethical dilemmas such as ‘is it ok to steal?’

For utilitarian theories, what matters is the consequence of an action. If your stealing a loaf of bread, say, prevents your family from dying of starvation, then the annoyance of the shopkeeper is likely to be outweighed by your happiness that your family is still alive. So stealing the bread is morally permissible.

Kant’s deontological ethics takes a rule-based approach. According to Kant, there are certain moral laws that are universal and we have a duty to follow them. He provides two tests to determine what these laws are. Based on these tests, Kant would say stealing is always wrong, regardless of the consequences.

Aristotle’s virtue theory takes a different approach to both Kant and utilitarianism. Kant and utilitarianism both give formulas for what to do, whereas Aristotle is more concerned with what sort of person we should be. So, if a virtuous person would not steal in a particular set of circumstances, then it is wrong to steal in those circumstances.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarian ethical theories are consequentialist. They say that it’s the consequences of an action that make it either right or wrong.

The most obviously relevant consequences are pain and pleasure. Generally speaking, utilitarian theories look to minimise pain and maximise pleasure.

For example, a utilitarian might argue that it is justified for a poor person to steal from a rich person because the money would cause more happiness for the poor person than it would cause unhappiness for the rich person. Similarly, a utilitarian might argue that murder is justified if the victim is himself a murderer and so killing him would save 10 lives.

The syllabus looks at 3 different versions of ultilitarianism:

- Act utilitarianism: we should act so as to maximise pleasure and minimise pain in each specific instance

- Rule utilitarianism: we should follow general rules that maximise pleasure and minimise pain (even if following these rules doesn’t maximise pleasure in every specific instance)

- Preference utilitarianism: we should act to maximise people’s preferences (even if these preferences do not maximise pleasure and minimise pain)

Act utilitarianism

“The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation.”

– Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham is widely considered to be the first utilitarian philosopher. His act utilitarianism can be boiled down to three claims:

- Whether an action is right/good or wrong/bad depends solely on its consequences

- The only thing that is good is happiness

- No individual’s happiness is more important than anyone else’s

The felicific calculus

Act utilitarianism is sometimes called quantitative utilitarianism. It’s called quantitative because it’s about quantifying happiness – adding up all the happiness and subtracting all the pain – and then deciding how to act based on the numbers. Bentham provides the felicific calculus as a way to calculate utility in this way.

- Intensity: how strong the pleasure is

- Duration: how long the pleasure lasts

- Certainty: how likely the pleasure is to occur

- Propinquity: how soon the pleasure will occur

- Fecundity: how likely the pleasure will lead to more pleasure

- Purity: how likely the pleasure will lead to pain

- Extent: the number of people affected

So, for example, if two different courses of action lead to two different intensities of pleasure, then the ethically right course of action is the one that leads to the more intense pleasure. It gets complicated, though, when comparing intensity with duration, say.

Anyway, the felicific calculus should (in theory) provide a means to calculate the total happiness: add up all the pleasures and minus all the pains.

Act utilitarians would agree that the morally good action is the one that maximises the total happiness.

Problems

Note: Many of the problems with act utilitarianism below inspired the alternative versions of utilitarianism (e.g. rule and preference). If you are writing an essay (i.e. 25 marks) on utilitarianism you can use these to argue against act utilitarianism but for an alternative type of utilitarianism.

Difficult to calculate

Although act utilitarianism may seem simple in principle, in practice there are all sorts of difficulties with calculating utility.

For one thing, you can’t predict the future. For example, saving a child’s life would presumably a good way to maximise pleasure. But if that child went on to become a serial killer as an adult, saving their life could have actually been a bad thing according to utilitarianism – but how were you to know?

But even if we could predict the future, Bentham’s felicific calculus seems impractically complicated to use every single time one has to make a decision:

- First, how do you quantify each of the seven variables? For example, how do you measure the intensity of pleasure? Are we supposed to hook everyone up to brain scanners?!

- Second, how do you compare these seven variables against each other? For example, how do you decide between, say, a longer-lasting dull pleasure and a short-lived but more intense pleasure?

- Finally, which beings do we include in this calculation? Animals can feel pleasures and pains too, so are we supposed to include them in our calculation? If so, is a dog’s pain equal to a human being’s? What about a mouse? Or a spider?

It all gets very complicated. Are we really supposed to predict all future outcomes, quantify all these variables, compare them, and calculate which act maximises utility most effectively? And every single time we act?! That’s just not practical!

Possible response:

Bentham says the felicific calculus is more a general guide to be “kept in view” rather than something that has to be worked out precisely every time we act:

“It is not to be expected that this process should be strictly pursued previously to every moral judgment, or to every legislative or judicial operation. It may, however, be always kept in view.”

– Jeremy Bentham, Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Chapter 4

Tyranny of the majority

There are some things that just seem wrong regardless of the consequences.

For example, imagine a scenario where a nasty murder has taken place and an angry crowd are baying for blood. In other words, it would make the crowd happy to see the perpetrator apprehended and punished for his crimes.

But what if the police can’t catch the murderer? They could just lie and frame an innocent man instead.

If the crowd believe the murderer has been caught (even if it’s not really him) then they would be just as happy whether it was the actual perpetrator or not.

And let’s say the crowd is 10,000 people. Their collective happiness is likely to outweigh the innocent man’s pain at being falsely imprisoned. After all, there are 10,000 of them and only one of him (hence, tyranny of the majority).

In this situation an act utilitarian would have to say it’s morally right to imprison the innocent man. In fact, it would be morally wrong not to!

Possible response: rule utilitarianism.

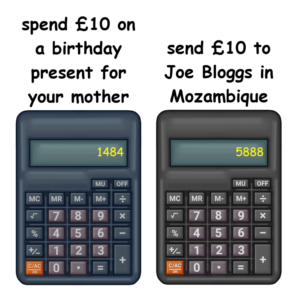

Moral status of particular relationships

Certain people – namely, friends and family – are more important to us than others.

But act utilitarianism is concerned only with the greatest good for the greatest number. There are no grounds, then, to justify acting to maximise their happiness over some random person on the street.

This means, for example:

- That £10 you spend buying your mum a birthday present made her happy, sure, but it would have made Joe Bloggs in Mozambique happier. So, buying your Mum a birthday present was morally wrong according to utilitarianism.

- The time you spent with your friends made them happy, but volunteering at the local soup kitchen would have increased the greatest good for the greatest number more effectively. So, you acted wrongly by spending time with your friends because this did not maximise the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

You get the idea. If we sincerely followed act utilitarianism we would never be morally permitted to spend time and money with our loved ones.

This objection can be used to show that act utilitarianism is too idealistic and doesn’t work in practice. Or, you could argue that certain relationships have a unique moral status and that act utilitarianism forces us to ignore these moral obligations.

Ignores intentions

What makes an action right or wrong according to utilitarianism is whether it increases happiness. So, if someone tries to do something evil but accidentally increases happiness, then utilitarianism says what they did was good.

For example, imagine some villain tries to kill everyone in town by poisoning the water supply. However, he doesn’t have enough poison and so instead of killing anyone he ends up getting everyone mildly high and causing them pleasure.

For example, imagine some villain tries to kill everyone in town by poisoning the water supply. However, he doesn’t have enough poison and so instead of killing anyone he ends up getting everyone mildly high and causing them pleasure.

According to utilitarianism, what this villain did was good – he increased overall pleasure. But what he did was clearly bad – his intention was to commit mass murder. But utilitarianism ignores this.

Higher and lower pleasures

We saw above how Bentham’s felicific calculus seeks to quantify happiness. However, we can argue that this quantitative approach makes utilitarianism a ‘doctrine of swine’ in that it reduces the value of human life to the same simple pleasures felt by pigs and animals.

Possible response:

However, in response to this objection, utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill rejects Bentham’s felicific calculus and argues that not all pleasures and pains are equally valuable. Mill argues that people who have experienced the higher pleasures of thought, feeling, and imagination always prefer them to the lower pleasures of the body and the senses. Higher pleasures, he says, are more valuable than simple pleasures.

So, Mill takes a qualitative approach to happiness rather than Bentham’s purely quantitative approach. Returning to the ‘doctrine of swine’ objection, Mill argues that humans prefer higher pleasures over lower pleasures because they value dignity – and dignity is an important component of happiness. Thus, Mill famously says:

“It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.”

John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism

Other values/preferences beyond happiness

There are situations where we might prefer something even if it makes us less happy, and situations where we might prefer something not happen even though it would make us more happy.

Philosopher Robert Nozick’s experience machine thought experiment illustrates this point: Imagine you could be plugged into a virtual reality machine that simulates the experience of a perfect life. In other words, the machine maximises your happiness and minimises your pain. Once plugged in, you don’t know you’re in a virtual reality and you believe your perfect life is completely real.

Philosopher Robert Nozick’s experience machine thought experiment illustrates this point: Imagine you could be plugged into a virtual reality machine that simulates the experience of a perfect life. In other words, the machine maximises your happiness and minimises your pain. Once plugged in, you don’t know you’re in a virtual reality and you believe your perfect life is completely real.

Yet despite maximising happiness, many people would prefer not to enter the experience machine. These people would prefer to live a real life and be in contact with reality even though a real life means less happiness and more pain compared to the experience machine.

According to act utilitarianism, everyone should enter the experience machine (because all that matters is maximising happiness). But it seems morally wrong to ignore a person’s preferences and, say, force them to enter the experience machine in order to increase happiness.

This example illustrates a problem with Bentham and Mill’s hedonism (the idea that happiness and pleasure are the only things of value). We realise there are things in life more important than simple pleasure – such as being in contact with reality – but act utilitarianism ignores our preferences for these things.

Possible response: preference utilitarianism.

Rule utilitarianism

“though the consequences in the particular case might be beneficial—it would be unworthy of an intelligent agent not to be consciously aware that the action is of a class which, if practiced generally, would be generally injurious, and that this is the ground of the obligation to abstain from it.”

John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism

Rule utilitarianism focuses on the consequences of general rules rather than specific actions (act utilitarianism). Rules are decided on the basis of whether they increase happiness, and actions are deemed right or wrong depending on whether they are in accordance with these rules.

This provides a response to the tyranny of the majority objection to act utilitarianism above. Although in this specific instance punishing the innocent man leads to greater happiness, as a general rule punishing innocent people leads to more unhappiness. For example, if you lived in a society where you knew innocent people were regularly framed, you would worry that it might happen to you. There would also be no satisfaction in seeing criminals ‘brought to justice’ as there would be no way to know whether they were guilty.

Similarly, rule utilitarians may defend rules such as ‘don’t steal’ or ‘don’t lie’ as, in general, following these rules increases happiness.

Possible response:

Rule utilitarians are often categorised into two camps, but each raises problems:

- Strong rule utilitarianism: Strictly follow the rules – even in instances where breaking them would lead to greater happiness.

- Problem: This leads to ‘rule worship’ and loses sight of the whole point of utilitarianism, which is to increase happiness. If the rule ‘don’t lie’ increases happiness in general, then you can’t tell a lie even in a situation where doing so would save everyone on earth, for example.

- Weak rule utilitarianism: Follow the rules – unless breaking the rule would lead to greater happiness.

- Problem: But then how is this different from act utilitarianism? If we can break the rule whenever the consequences justify doing so, then there’s no point of having the rule and we’re back to the tyranny of the majority.

Preference utilitarianism

Preference utilitarianism is a non-hedonistic form of utilitarianism. It says that instead of maximising happiness (hedonistic utilitarianism), we should act to maximise people’s preferences.

This provides a response to the experience machine objection to act utilitarianism above. Act utilitarianism says we should shove everyone into the experience machine – whether they want to go in or not – because doing so would maximise their happiness. However, preference utilitarianism can reject this by saying we should respect people’s preference to live in the real world (even if living in the real world means less happiness).

A related example would be carrying out the wishes of the dead. It can’t increase the happiness of a deceased person to carry out their will (because they’re dead). However, if a deceased person expressed a preference for their money to be donated to the local cat shelter, say, then it seems there is a moral obligation to honour this preference. Act utilitarianism, though, would say we should ignore the preferences of the deceased and just spend the money in whichever way maximises happiness – but this seems wrong. Preference utilitarianism can avoid this outcome and say we should respect the preferences of the dead.

Preference utilitarianism can also tie in with Mill’s distinction between higher and lower pleasures. Mill claims that higher pleasures are just inherently more valuable than lower pleasures, but preference utilitarianism can explain this in terms of preference: We prefer higher pleasures over lower pleasures, and so should seek to maximise those.

Possible response:

How to decide between competing preferences?

Or what if someone has stupid, or even evil, preferences? If preferences are what make things good or bad, then what grounds does preference utilitarianism have to say a preference to spend your life curing cancer is any better, morally, than a preference to spend your life torturing animals?

Kant’s deontological ethics

Kant’s theory is quite long-winded, but it can be summarised as:

- The only thing that is good without qualification is good will.

- Good will means acting for the sake of duty.

- You have a duty to follow the moral law.

- Moral laws are universal.

- You can tell is a maxim is universal if it passes the categorical imperative.

- The categorical imperative is two tests:

- Contradiction in conception

- Contradiction in will

- Finally, do not treat people as means to an end (the humanity formula).

The good will

Good will is one that acts for the sake of duty. This, according to Kant, is the source of moral worth.

So, if you save someone’s life because you expect to be financially rewarded, this action has no moral worth. You’re acting for selfish reasons, not because of duty.

However, if you save someone’s life because you recognise that you have a duty to do so, then this action does have moral worth.

Duty

Deontology (as in Kant’s deontological ethics) is the study of duty.

Kant argues that we each have a duty to follow the moral law. The moral law, according to Kant, is summarised by the categorical imperative.

The categorical imperative

“Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law without contradiction.”

– Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals

There are two kinds of maxims (rules): categorical and hypothetical.

- Hypothetical rules are qualified by an ‘if’ statement,

- E.g. “you should do your homework if you want to do well in the exam.“

- Categorical rules are not qualified by an ‘if’ statement, they apply universally.

- E.g. “you shouldn’t steal” is a rule that applies to everyone, i.e. it applies universally.

According to Kant, moral laws are categorical, not hypothetical. Kant gives two ways to test whether a maxim/rule passes the categorical imperative: contradiction in conception and contradiction in will. He also gives another formula for the categorical imperative, called the humanity formula.

Test 1: contradiction in conception

For a law to be universal, it must not result in a contradiction in conception.

A contradiction in conception is something that is self-contradictory.

Example: we might ask Kant whether it is morally acceptable to steal. I.e., we might ask whether “you should steal” is a universally applicable maxim.

If stealing was universally acceptable, then you could take whatever you wanted from someone, and the owner of the object would have no argument against it. In fact, the very concept of ownership wouldn’t make sense – as everyone would have just as much right to an object as you do.

So, in a world where stealing is universally acceptable, the concept of private property disappears. If there is no such thing as private property, then stealing is impossible.

Therefore, Kant would say, the maxim “you should steal” leads to a contradiction in conception. Therefore, stealing is not morally permissible.

If a maxim leads to a contradiction in conception, you have a perfect duty not to follow that maxim. It is always wrong.

Test 2: contradiction in will

Assuming the maxim does not result in a contradiction in conception, we must then ask whether the maxim results in a contradiction in will – i.e. whether we can rationally will a maxim or not.

Example: can we rationally will “not to help others in need”?

There is no contradiction in conception in a world where nobody helps anyone else. But we cannot rationally will it, says Kant. The reason for this is that sometimes we have goals (Kant calls these ends) that cannot be achieved without the help of others. To will the ends, we must also will the means.

So, we cannot rationally will such goals without also willing the help of others (the means).

Of course, not all goals require the help of others. Hence, Kant argues this results in an imperfect duty. In other words, it is sometimes wrong to follow the maxim “not to help others in need”.

The humanity formula

Kant gives another formulation of the categorical imperative:

“Act in such a way that you always treat humanity […] never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.”

– Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals

Treating someone as a means to your own end means to use them. So Kant is basically saying don’t use people.

Example: tricking someone into marrying you.

If you pretend to love someone to marry them and take their money, you treat them as a means to make money.

According to Kant, it’s the deception that is the problem here as it undermines the rational agency of the other party. By withholding your true intentions, you prevent the other party from rationally pursuing their own ends (e.g. to find a loving partner).

But if you’re honest with the other party, the other party can make an informed choice on whether this fits with their ends. Their goal might be to get married to anyone, regardless of whether it’s love or not. In this case you can both (rationally) use each other for mutual benefit. You acknowledge each others ends, even if they are not the same.

Problems

Not all universal maxims are moral (and vice versa)

Kant argues that ignoring a perfect duty leads to a contradiction in conception. As we saw in the stealing example, the very concept of private property couldn’t exist if stealing was universally permissible. But by tweaking the maxim slightly, we can avoid this contradiction in conception and justify stealing.

For example, instead of my maxim being ‘to steal’, I could claim my maxim is ‘to steal from people with nine letters in their name’ or ‘to steal from stores that begin with the letter A’.

Both of these maxims can be universalised without undermining the concept of private property. They would apply rarely enough that there would be no breakdown in the concept of private property.

For Kant, if a maxim can be universalised, it is morally acceptable. But this shows that universalisable maxims are not necessarily good or moral.

You can also make this objection the other way round by appealing to maxims that can’t be made into universal laws and yet aren’t morally wrong.

For example, my maxim ‘to be in the top 10% of students’ can’t be made universal law because only 10% of people (by definition) can achieve this. And yet, it’s not morally wrong to try to be in the top 10% of students.

Possible response:

In the ‘stealing from people with nine letters in their name‘ example, Kant would likely argue that modifying your maxim in this way is cheating because the extra conditions – such as the number of letters in a person’s name or the name of the store – are morally irrelevant to this situation.

The categorical imperative is concerned with the actual maxim I am acting on and not some arbitrary one I just made up.

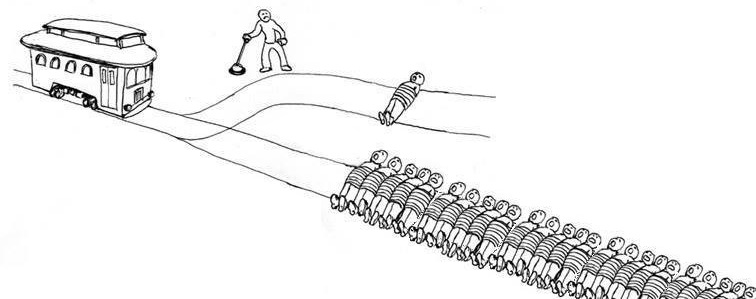

Ignores consequences

There is a strong intuition that consequences (i.e. utilitarianism) are important when it comes to moral decision making.

This intuition can be drawn out by considering ethical dilemmas such as the trolley problem:

Is it right to kill one person to save five people? Kant would say no, a utilitarian would say yes.

But what about 100 people? Or the entire population of the world? Surely if the consequences are significant enough we should consider breaking certain rules?

Another example is stealing. Many people would have the utilitarian intuition that it’s morally acceptable to steal food in some situations – for example, stealing food to save your starving family’s life. However, Kant says we have a perfect duty never to steal and so you should just let your family starve to death – but this doesn’t seem right.

The problem with such rigid rules is drawn out further in the lies section of applied ethics. Kant argues that we have a perfect duty not to lie – even if telling a lie would save someone’s life.

These thought experiments seem to draw out absurd and morally questionable results from following rules too strictly.

Ignores other valuable motivations

In the discussion of the good will, we saw how Kant argues that acting for the sake of duty is the source of moral worth.

In other words, being motivated by duty is the only motivation that has moral worth.

So, imagine a close friend is ill in hospital. You pay them a visit because you genuinely like them and want to make sure they’re ok. According to Kant, this motivation (concern for your friend) has no moral value.

However, if you didn’t really care about your friend but begrudgingly went to visit purely out of duty, this would have moral value according to Kant.

But this seems absurd. Kant seems to be saying we should want to help people because of duty, not because we genuinely care.

Possible response:

Kant would respond by making a distinction between acting for the sake of duty and acting in accordance with duty. There is nothing wrong with being motivated by motivations such as love, but we shouldn’t choose how to act because of them. Instead, we should always act out of duty, but if what we want to do anyway is in accordance with duty then that’s a bonus.

Conflicts between duties

Kant argues that it is never acceptable to violate our duties.

But what if you find yourself in a situation where such a situation was unavoidable? For example, Kant would say we have a duty to never lie. But what happens if you make a promise to someone but then find yourself in a situation where the only way to keep that promise is by telling a lie? Whichever choice you make you will seemingly violate one of your duties.

Possible response:

Kant claims that a true conflict of duties is impossible. Our moral duties are objective and rational and so it is inconceivable that they could conflict with one another. If it appears that there is a conflict in our duties, he says, it must mean we have made a mistake somewhere in formulating them. After all, you can’t rationally will a maxim to become a universal law if it conflicts with another law you rationally will – that would be contradictory.

So, if we think through our duties carefully, Kant says, a true conflict is irrational and inconceivable. Applied to the example above, Kant could say we shouldn’t make a promise that could conflict with our moral duties.

Foot: Morality as a system of hypothetical imperatives

Philippa Foot argues that moral laws are not categorical in the way Kant thinks – there is no categorical reason to follow them. Instead, she argues, morality is a system of hypothetical imperatives:

| Hypothetical imperatives | Categorical imperatives |

| Qualified by an ‘if’ statement | Not qualified by an ‘if’ statement, they apply universally |

| You should do x if you want y | You should do x (all the time, whoever you are, without exception) |

E.g.:

|

E.g.:

|

The motivation for hypothetical imperatives is obvious: I should do my homework because I want to do well in the exam. I should leave now because I want to catch the train on time. These desires provide a rational reason why I should act according to these imperatives.

However, the reason for categorical imperatives is not so clear. Why shouldn’t I steal? Why shouldn’t I tell lies? If I don’t care about these rules – if I have no desire to follow them – then why should I? Kant would say following moral laws is a matter of rationality and that reason tells us we should follow the categorical imperative but Foot argues that:

“The fact is that the man who rejects morality because he sees no reason to obey its rules can be convicted of villainy but not of inconsistency. Nor will his action necessarily be irrational. Irrational actions are those in which a man in some way defeats his own purposes […] Immorality does not necessarily involve any such thing.”

– Philippa Foot, Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives

In other words, there is nothing irrational about disobeying the categorical imperative if you never accepted it in the first place. The categorical imperative does not itself provide any rational reason to follow it. We might feel that there is some moral force that compels us not to steal or tell lies but this feeling is just that: a feeling. In reality, there is no real reason to follow moral laws any more than there is reason to follow the rules of etiquette, such as “handshakes should be brief”.

Instead, Foot argues that we should see morality as a system of hypothetical, rather than categorical, imperatives. For example:

- You shouldn’t steal if you don’t want to upset the person you’re stealing from

- You shouldn’t tell lies if you care about having integrity

- You shouldn’t murder if you want to be a just and virtuous person

Aristotle’s virtue theory

Like Kant, Aristotle’s ethics are somewhat long-winded. Aristotle also makes a bunch of different arguments that can sometimes seem a bit unconnected.

The first thing to say is that Aristotle starts by answering a slightly different question to Kant and utilitarianism. Instead of answering “what should I do?” (action-centred) he addresses a question more like “what sort of person should I be?” (agent-centred). It’s basically the other way round: Instead of defining a good person as someone who does good actions, Aristotle would define good actions as those done by good people.

The following is a brief summary of his main points:

- Eudaimonia = the good life for human beings

- The good life for a human being must consist of something unique to human beings

- Human beings are rational animals, and reason is their unique characteristic activity (ergon)

- The good life (eudaimonia) is one full of actions chosen according to reason

- Virtues are character traits that enable us to act according to reason

- The virtue is the middle point between a vice of deficiency and a vice of excess

- Virtues are developed through habit and training

Eudaimonia

You can have good food, good friends, a good day. Aristotle’s ethical enquiry is concerned with the good life for a human being. The word Aristotle uses for this is eudaimonia, which is sometimes translated as ‘human flourishing’.

Aristotle has in mind the good life for a human in a broad sense. Eudaimonia is not just about following moral laws (e.g. Kant), or being happy (e.g. utilitarianism), or being successful – it’s about all these things together and more. It’s a good life in the moral sense as well as in the sense that it’s the kind of desirable and enjoyable and valuable life you would want for yourself.

Eudaimonia is a property of someone’s life taken as a whole. It’s not something you can have one day and then lose the next. Good people sometimes do bad things, but this doesn’t make them bad people. Likewise, people who have good lives (eudaimons) can sometimes have bad days.

Aristotle says that eudaimonia is a final end. We don’t try to achieve eudaimonia as a means to achieve some goal but instead it is something that is valuable for its own sake.

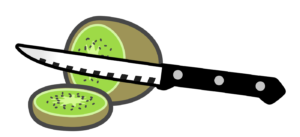

Arête, ergon, and virtue

While fleshing out this concept of eudaimonia, Aristotle uses the words arête and ergon. These roughly translate as:

- Ergon: function/characteristic activity of a thing

- Arête: property/virtue that enables a thing to achieve its ergon

For example, a knife’s ergon is to cut things. And a good knife has the arête of sharpness because this enables it to cut things well.

For example, a knife’s ergon is to cut things. And a good knife has the arête of sharpness because this enables it to cut things well.

Aristotle argues that eudaimonia must consist of something unique to humans. The ergon of humans, says Aristotle, is to use reason. Reason is what makes us unique from trees, plants, books, knives, animals – everything else in the world. However, this does not mean that we achieve eudaimonia by doing nothing but idly thinking and reasoning. Instead, Aristotle’s claim is that humans always choose their actions for some reason – good or bad. So, what Aristotle actually says is that the good life for a human being (eudaimonia) is one full of actions chosen according to good reason.

Virtues are character traits that enable us to choose our actions according to good reason. So, just as the arête of sharpness helps a knife fulfil its ergon to cut things, the arête of virtues help humans fulfil their ergon, which is to choose actions according to reason.

A bit like eudaimonia, virtues are not something you have one day but not the next. If someone has a virtuous character but slips up one day and does something unvirtuous, this doesn’t make them a bad person. Likewise, a bad person whose character is prone to vice doesn’t suddenly develop virtuous character through committing one virtuous act. So, again, virtues are character traits – they are part of what we are.

The doctrine of the mean

Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean (also called the golden mean) provides more detail about what virtuous character traits actually are. The doctrine of the mean says that virtues are the intermediate or average (the mean) between two extremes.

For example, if you never stand up for yourself then you are cowardly (vice of deficiency). But if you go too far the other way and start fights with anyone for the slightest reason then you are reckless (vice of excess). The correct and virtuous way to act is somewhere in between these two extremes.

Some other examples:

| Vice of deficiency | Virtue |

Vice of excess |

| Cowardice | Courage | Recklessness |

| Shy | Modest | Shameless |

| Stingy | Liberal | Wasteful |

| Self-denial | Temperance | Self-indulgence |

| Surly | Friendly | Obsequious |

Again, virtues are character traits. So, for example, just because you have a good-tempered character in general this doesn’t mean you should always be good-tempered in every situation.

There are times when anger is the appropriate (and virtuous) response. The virtuous person is not someone who never feels angry or other extremes of emotions. Instead, the virtuous person is someone whose character disposes them to feel these extreme emotions when it is appropriate to do so. As Aristotle says:

“For instance, both fear and confidence and appetite and anger… may be felt both too much and too little, and in both cases not well; but to feel them at the right times, with reference to the right objects, towards the right people, with the right motive, and in the right way, is what is both intermediate and best, and this is characteristic of virtue.”

Aristotle, The Nichomachean Ethics Book II.VI

The skill analogy

Acquiring virtues is somewhat analogous to acquiring skills such as learning to ride a bike or play the piano:

- Nobody is born knowing how to play the piano, but we are born with the capacity to know how to play the piano. Likewise, nobody is born virtuous, but they have the capacity to become virtuous

- You don’t learn to play the piano by simply reading books and just studying the theory, you have to actually do it. Likewise, it’s not enough to just read and learn about virtue, you have to actually act virtuously until it becomes part of your character.

- When you first start learning to play the piano, you follow the rules and try not to press the wrong keys – but you don’t really understand what you’re doing. In the case of virtue, we start by teaching children rules for behaviour (e.g. “don’t eat too many sweets” or “if you haven’t got anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all”) and they just follow these rules because they’re told to – not because they understand why.

- But as you progress with playing the piano, you become able to play automatically without thinking and, eventually, you might become so comfortable playing the piano that you’re able to improvise and understand what sounds good, what doesn’t, and why. Likewise, by following rules for acting virtuously, it eventually becomes part of our character (e.g. we develop the virtue of temperance by repeatedly refusing to indulge until it eventually becomes habit). Further, we begin to understand what virtue is and this enables us to improvise according to what the situation demands.

Phronesis

Another of Aristotle’s terms is phronesis, which translates as something like ‘practical wisdom’.

Aristotle’s virtue ethics is not like Kant’s deontological ethics where what is good/right can be boiled down to a list of general rules. For Aristotle, what’s good/right will depend on the specific details of the situation. In one situation (out with your friends, say) it might be virtuous to tell a joke whereas in another situation (e.g. at a funeral) it would be inappropriate. Knowing what virtue requires according to the specific details of the situation requires a practical wisdom. For Aristotle, this means:

- Having a general understanding of what is good for human beings (eudaimonia).

- Being able to apply this general understanding to the specific details of the situation – the time, the place, the people involved, etc.

- Being able to deliberate (i.e. think through) what is the virtuous goal according to these specific details.

- And then acting virtuously according to this deliberation to achieve this virtuous outcome.

As the name suggests, practical wisdom is not the sort of thing you can learn from books – it’s practical. The skill analogy illustrates how virtuous actions become habit over time, leading to virtuous character that enables us to act virtuously in the wide variety of situations we find ourselves.

Moral responsibility

Aristotle says we should only praise or condemn actions if they are done voluntarily. In other words, you can’t criticise someone for acting unvirtuously if their actions weren’t freely chosen.

- Voluntary: acting with full knowledge and intention

- Involuntary/non-voluntary:

- Compulsion (i.e. involuntary): being forced to do something you don’t want to do – e.g. sailors throwing goods overboard to save the boat during a storm

- Ignorance (i.e. non-voluntary): doing something you don’t want to do by accident – e.g. slipping on a banana skin and spilling a drink on someone

Aristotle says a person is only morally responsible for their voluntary actions.

Problems

No clear guidance

Aristotle describes virtues in the middle of the two extremes (the doctrine of the mean) and that this varies depending on the situation. But this isn’t very helpful as a practical guide of what to do.

For example, Aristotle would say it is correct to act angrily sometimes – but when exactly? And how angry are you supposed to get before it crosses over from a virtue to a vice of excess?

Kant gives the categorical imperative as a test to say whether an action is moral or not. And even utilitarianism has the felicific calculus. But with Aristotle, we have no such criteria against which to judge whether one course of action is better than another. The doctrine of the mean doesn’t give actual quantities, only vague descriptions as “not too much” and “not too little”. If you genuinely don’t know what the correct course of action is, virtue theory doesn’t provide any actual guidance for how to act.

Possible response:

Aristotle could reply that virtue theory was never intended to provide a set of rules for how to act. Life is complicated – that’s the whole reason why you need to develop practical wisdom in the first place, so you can act virtuously in the many complicated situations that arise. Plus, we can still reflect whether an action is, for example, courageous or stupid. We could also ask questions like “how could I be more friendly in this situation?” that help us decide how to act. Just because virtue theory doesn’t provide a specific course of action, that does not mean it provides no guidance whatsoever.

Circularity

Aristotle can be interpreted as defining virtuous acts and virtuous people in terms of each other, which doesn’t really say anything. He’s basically saying something like:

- A virtuous act is something a virtuous person would do

- And a virtuous person is a person who does virtuous acts

These descriptions are circular and so say nothing meaningful about what a virtuous person or a virtuous act actually is.

Competing virtues

We can imagine scenarios where applying two different virtues (e.g. justice and mercy) would suggest two different courses of action.

For example, if you’re a judge and someone has stolen something, you have to choose between the virtue of justice (i.e. punishing the criminal) and the virtue of mercy (i.e. letting the criminal go). You can’t choose to do both things, so whichever choice you make will be unvirtuous in some way.

Possible response:

Aristotle would reply that such conflicts between virtues are impossible. As mentioned in the no clear guidance objection, virtues are not rigid and unbreakable rules and the correct virtue and in what amount depends on the circumstances. Aristotle would say that practical wisdom would mean knowing what each virtue tells you to do and in what amount. So, for example, you could sentence a person according to justice, but show appropriate mercy if there are extenuating circumstances.

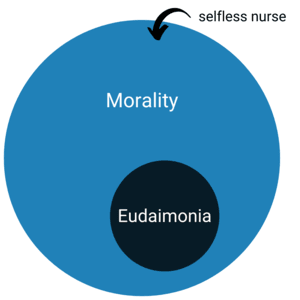

Difference between eudaimonia and moral good

According to Aristotle, the good life for a human being is eudaimonia. And, as mentioned, eudaimonia includes many elements beyond simply being moral – such as honour, wealth, and happiness. However, we often make a distinction between a good life for me (eudaimonia) and a morally good life.

For example, imagine a nurse who spends her entire life saving lives in some remote country. She doesn’t enjoy her work, but does it because she believes it’s needed. She’s constantly stressed and dies at age 30 from a virus caught while carrying out her work. With such an example, we tend to have a strong intuition that this nurse’s life is morally good (she’s done nothing but help other people) but she clearly did not achieve eudaimonia.

For example, imagine a nurse who spends her entire life saving lives in some remote country. She doesn’t enjoy her work, but does it because she believes it’s needed. She’s constantly stressed and dies at age 30 from a virus caught while carrying out her work. With such an example, we tend to have a strong intuition that this nurse’s life is morally good (she’s done nothing but help other people) but she clearly did not achieve eudaimonia.

This suggests there is a difference between what is morally good and eudaimonia, and so Aristotle’s virtue ethics fails as an account of what morality is.

Possible response:

You could respond, however, that Aristotle was never trying to answer the (narrow) question of what a morally good life is. Aristotle’s inquiry and eudaimonia is concerned with the good life in general – human flourishing in a broad sense. Further, Aristotle would likely argue that achieving eudaimonia does involve some level of commitment to others. So, the kind of altruism demonstrated by the nurse in the example above would indeed be part of eudaimonia – it’s just not the only part. In other words, being morally good is necessary, but not sufficient, for eudaimonia.