Overview – Knowledge from Perception

This A level philosophy topic looks at 3 theories of perception that explain how we can acquire knowledge from experience, i.e. a posteriori. They are:

The theories disagree over the metaphysical question of whether the external world exists (realism vs. anti-realism) and the epistemological question the way we perceive it (direct vs. indirect). Each theory also has various arguments for and against. These key points are summarised below:

| Direct Realism | Indirect Realism | Idealism | |

|

|

||

| External world | Mind-independent | Mind-independent | Mind-dependent |

| Perception method | Direct | Indirect (via sense data) | Direct |

| Philosophers |

|

|

|

| Problems |

Direct Realism

“The immediate objects of perception are mind-independent objects and their properties.”

Direct realism is the view that:

- The external world exists independently of the mind (hence, realism)

- And we perceive the external world directly (hence, direct)

So, basically, what you see is what you get.

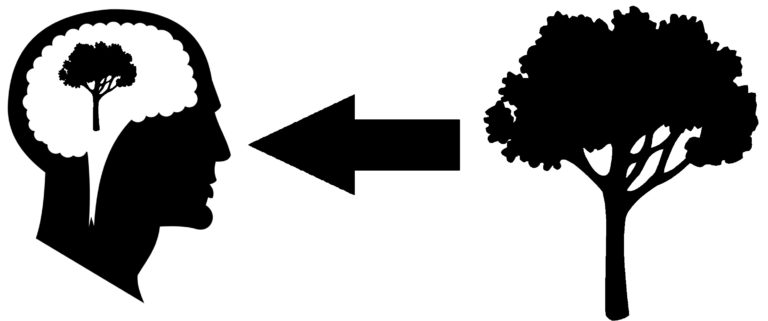

When you look at, and perceive, a tree, you are directly perceiving a tree that exists ‘out there’ in the world. You are also perceiving its properties (size, shape, smell, etc.).

So, the immediate objects of perception are mind-independent objects and their properties.

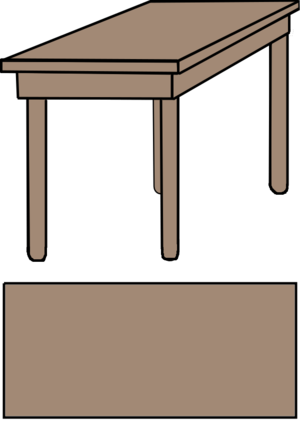

Direct realism is often thought of as the common sense theory of perception. When asked what you see, you describe the external object itself, not your perception of it. For example:

“What do you see?”

“A table.”

You wouldn’t respond with:

“Brown patches of sense data in a rectangular arrangement.”

At least on the face of it, perceptual experience presents itself to us as mind-independent objects. However, there are a number of issues with this simple explanation.

Problems for direct realism

Bertrand Russell: Argument from perceptual variation

Differences in perceptual variation provide a problem for direct realism.

For example, when I stand on one side of the room, a shiny wooden table may appear to have a white spot where the light is shining on it. But to someone standing on the other side of the room, there may be no white spot.

But the white spot is either there or it isn’t – it can’t be both! So, at least one of us is not perceiving the table directly as it is.

Russell also talks about the shape of a table. From directly overhead, it may appear to be rectangular. But from a few metres away it may look kite-shaped. Again, it can’t be both shapes!

- Direct realism says what we perceive are objects and their properties

- But, in at least one of these instances, we perceive a property that the object does not have

- So, in at least one of these instances, what we are perceiving is not the object or its properties

- So, direct realism is false.

Possible response:

Direct realism can respond by refining the theory and introducing the idea of relational properties.

A relational property is one that varies in relation to something else. For example, being to the North or South of something, or being left or right of something, are all real and mind-independent properties that something can have – but they vary relative to other objects. London has the (mind-independent) property of being South of Leeds, for example, but it’s not like London has the property of ‘Southness’ relative to all perceivers – if you’re in Spain then London is North of you.

Applying this to perception, we could say that the table has the (mind-independent) relational property of appearing kite-shaped relative to certain perceivers, whilst simultaneously having the (mind-independent) relational property of appearing square-shaped to other perceivers. The table has both these mind-independent properties, but which one you perceive will vary depending on where you are.

In other words: The object itself does not change, but the perceiver does – and thus the perceived properties of the object change.

Argument from illusion

Remember, direct realism says that we perceive the external world directly as it is.

But if this is true, how is it that reality (i.e. the external world) can be different to our perception of it?

For example, when a pencil is placed in a glass of water, it can look crooked. But it isn’t really crooked.

If direct realism is true, the external world would be exactly as we perceive it. However, in the case of illusions, there is an obvious difference between our perception and reality.

@philosophymania Illusions are a problem for direct realism https://philosophyalevel.com/aqa-philosophy-revision-notes/theories-of-perception/#Direct #philosophy #philosophytiktok #epistemology #alevelphilosophy ♬ original sound – philosophymania

Possible response:

Similar to the response to perceptual variation, the direct realist could reply that the pencil has the relational property of looking crooked to certain perceivers (even though it isn’t really crooked). However, this response fails to explain the argument from hallucination.

Argument from hallucination

This is a more extreme version of the argument from illusion.

Direct realism says that when we perceive something, we are perceiving something that exists in the external world (directly).

But during hallucinations – perhaps as a result of being ill or taking drugs – we perceive things that aren’t even there. For example, I might perceive a goblin on my sofa. But there’s clearly not a goblin on the sofa in (mind-independent) reality.

But during hallucinations – perhaps as a result of being ill or taking drugs – we perceive things that aren’t even there. For example, I might perceive a goblin on my sofa. But there’s clearly not a goblin on the sofa in (mind-independent) reality.

So what is causing these perceptions? It can’t be a (mind-independent) goblin because no such thing exists in reality!

Possible response:

The direct realist could argue that hallucinations are not perceptions at all – they’re imaginations.

Ordinarily, what we perceive are mind-independent objects. But in cases of hallucination, we confuse imagination for perception – a bit like in a dream. Just because there are these weird exceptions, it doesn’t mean that ordinary perceptions are not of mind-independent objects.

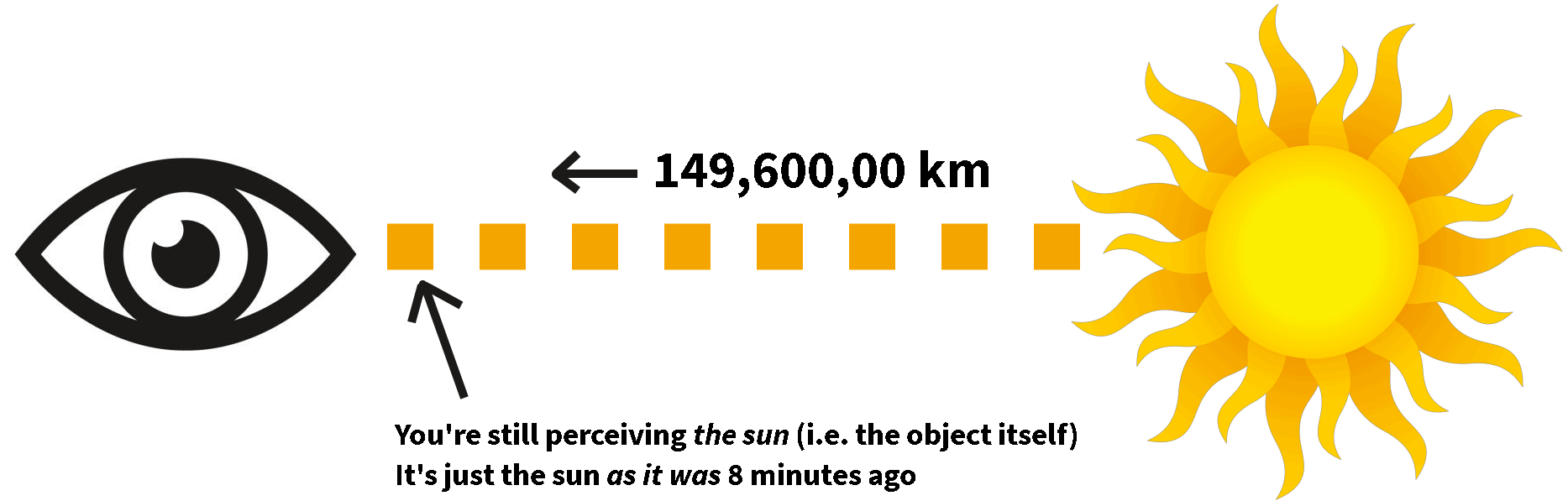

Time lag argument

The sun is 149,600,000 km from earth.

Light travels at 299,792,458 metres per second.

This means it takes approximately 8 minutes for light to reach earth.

So, when you look at the sun, you are seeing it as it was 8 minutes ago – i.e. there is a difference between the sun itself and your perception of it. In other words, you are not perceiving the sun directly.

Possible response:

The direct realist can argue that this response confuses what we perceive with how we perceive it. Yes, we perceive objects via light and sound waves and, yes, it takes time for these light and sound waves to travel through space. But what we are perceiving is still a mind-independent object (it’s not sense data or some other mind-dependent thing) – it’s just we are perceiving the object as it was moments ago rather than how it is now.

Indirect realism

“The immediate objects of perception are mind-dependent objects (sense-data) that are caused by and represent mind-independent objects.”

Indirect realism is the view that:

- The external world exists independently of the mind (hence, realism)

- But we perceive the external world indirectly, via sense data (hence, indirect)

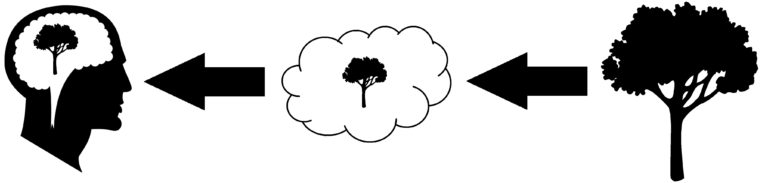

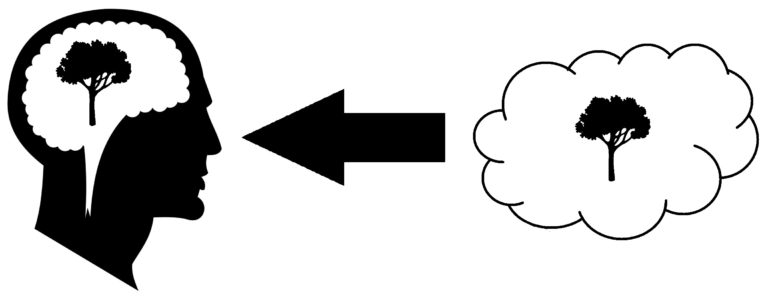

Indirect realism says the immediate object of perception is sense data. This sense data is caused by, and represents, the mind-independent external world.

Most philosophers who argue for indirect realism start with the problems for direct realism. The many differences between reality and our perception of it, they say, make direct realism implausible.

Instead, they claim that what we really perceive is sense data.

Sense data

Sense data can be described as the content of perceptual experience.

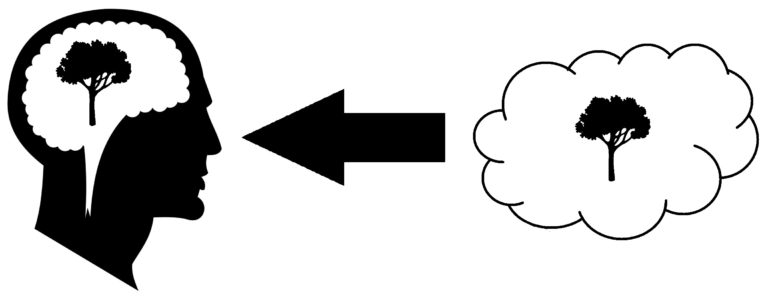

It’s not a physical thing, it exists in the mind. However, sense data is said to be caused by and represent mind-independent physical objects (see diagram above).

Sense data is private. No one else can experience your sense data.

This avoids the problems with direct realism described above. For example, differences in perceptual variation can be explained by differences in sense data. The object itself stays the same throughout even if the sense data changes.

John Locke: primary and secondary qualities

An idea closely related to sense data is John Locke’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities:

| Primary qualities | Secondary qualities |

| Properties inherent in the object itself | Powers of an object to cause sensations in humans |

| Objective | Subjective |

|

|

Locke uses various examples to illustrate this distinction.

One such example is porphyry – a red and white stone. Locke says that when you prevent light from reaching porphyry, “its colours vanish”. However, the primary qualities – size, shape, etc. – remain.

The distinction between primary and secondary qualities can be used to support indirect realism. Like sense data, this distinction explains the difference between reality (primary qualities) and our perception of it (secondary qualities).

For a problem with this view, see Berkeley’s criticism of the distinction between primary and secondary qualities.

Problems for indirect realism

Berkeley: Mind-independent objects are totally different to sense data

Again, indirect realism says something like: what we perceive is sense data that resembles the mind-independent external world. But George Berkeley (the idealism philosopher) questions how it’s possible for mind-dependent sense data to resemble so-called mind-independent objects in any way.

For example, sense data constantly changes, but mind-independent objects do not. The perceptual variation argument demonstrates this: One moment my sense data may be of a square table, the next it’s diamond-shaped. The sense data changes, but the mind-independent object doesn’t – so how can the two things resemble each other?

“How then is it possible, that things perpetually fleeting and variable as our ideas, should be copies or images of anything fixed and constant?”

– Berkeley, Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous, First Dialogue

Further, how can the properties of sense data be like the properties of mind-independent objects? We say that a table is square, but how can my sense data be square? How can the squareness of a (mind-independent) table be like the squareness of sense data? They are two completely different kinds of things!

These major differences between sense data and mind-independent objects undermine the indirect realist claim that sense data is caused by and resembles mind-independent objects.

Scepticism and the veil of perception

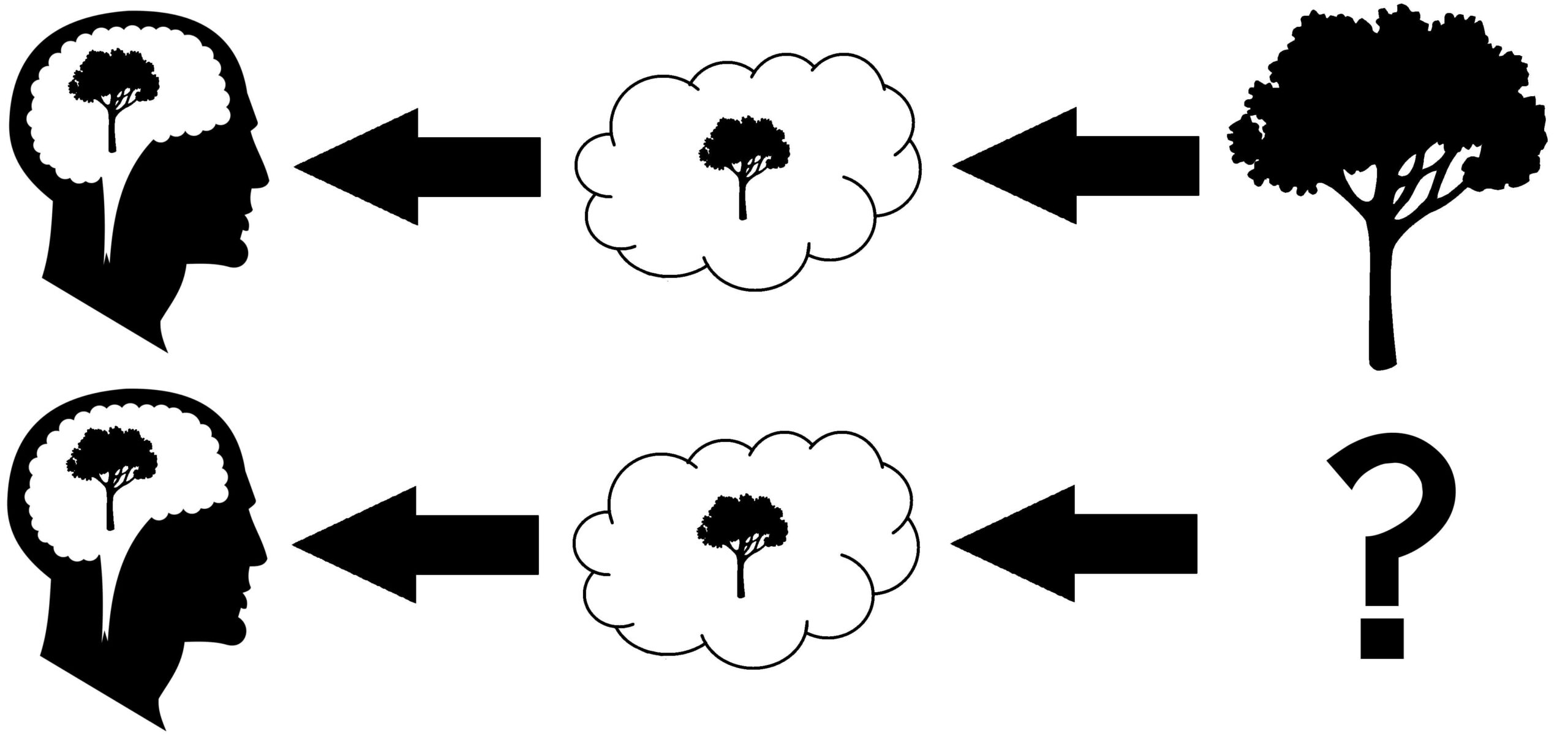

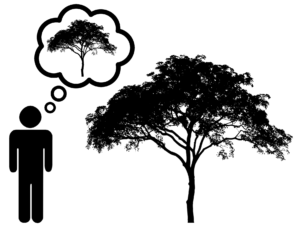

A problem for indirect realism is that it leads to scepticism about the nature and existence of the external world.

Look at the two diagrams above. What would be the difference from the perceiver’s perspective between the two? What difference would it make to the perceiver if there was no physical world at all?

The answer, surely, is nothing.

If we only perceive sense data, and not the object itself, how can we know anything about the external world? There is no way of telling if the sense data is an accurate representation of the external world – or even that there is an external world at all!

We can’t get beyond the veil of perception (sense data) to access the external world behind it. So, how can indirect realism justify its claim that there is a mind-independent external world that causes sense data if we never actually perceive the mind-independent external world itself?

Indirect realist replies to scepticism

Russell’s reply: External world is the best hypothesis

Bertrand Russell, an indirect realist, concedes that there is no way we can conclusively defeat this sceptical argument and prove the existence of the external world. So, instead, we must treat the external world as a hypothesis.

Imagine you see a cat sitting on the sofa. You go and make a cup of tea, and when you come back the cat is sitting on the floor. We can consider two explanations – two hypotheses – to explain these observations:

Imagine you see a cat sitting on the sofa. You go and make a cup of tea, and when you come back the cat is sitting on the floor. We can consider two explanations – two hypotheses – to explain these observations:

- Hypothesis A: The cat exists independently of my mind and while I was away making a cup of tea it walked from the sofa to the floor (passing through a series of physical positions along the way)

- Hypothesis B: The cat does not exist independently of my mind and so stopped existing while I was away making a cup of tea and sprung back into existence in a different location when I returned

Russell argues that hypothesis A – the existence of mind-independent objects – is a much better explanation than hypothesis B. For one thing, hypothesis A provides an explanation that connects the two perceptions (the cat on the sofa and the cat on the floor) whereas hypothesis B isn’t really an explanation at all. Hypothesis A also explains why, for example, the cat gets hungry even when I’m not perceiving it: The cat exists independently of my mind and so gets progressively more hungry even when I’m not perceiving it.

So, even though we can’t prove the existence of mind-independent objects, Russell argues we should believe in them since they are the best hypothesis to explain perceptions (btw, this is an example of an abductive argument).

Locke’s first reply: The involuntary nature of perception

John Locke offers two responses to the sceptical challenge.

First, Locke notes how he is unable to avoid having certain sense data produced in his mind when he looks at an object. By contrast, memory and imagination allows him to choose what he experiences. Locke concludes from this that whatever causes his perceptions must be something external to his mind as he is unable to control these perceptions.

“when my Eyes are shut […] I can at Pleasure re-call to my my Mind the Ideas of Light, or the Sun […] But if I turn my Eyes at noon towards the Sun, I cannot avoid the Ideas, which the Light, or Sun, then produces in me […] And therefore it must needs be some exteriour cause […] that produces those Ideas in my Mind.”

– Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Bk. 4, Ch. 11, §5)

Possible response:

However, even if Locke succeeds in proving something external, he doesn’t succeed in proving that sense data is in any way an accurate representation of the external world. The sceptic could argue that the external world may be completely different to our perception of it and there’s no way we could know.

Locke’s second reply: The coherence of different senses

Second, Locke argues that the different senses confirm the information of one another. He gives a couple of examples of this:

- Fire: “He that sees a Fire, may, if he doubt whether it be any thing more than a bare Fancy, feel it too; and be convinced, by putting his Hand in it.” (Bk. 4, Ch. 11, §7)

- A piece of paper with writing on it: You can write something on a piece of paper and see the words. Then, you can get someone to read the words out loud and thus hear the same information via a different source.

These examples suggest that the same mind-independent object causes both perceptions. If my visual perception of the fire, for example, was just something in my mind, then there would be no reason why I couldn’t sometimes feel coldness instead of heat. The fact that warmth always accompanies visual perceptions of fire suggests the same (mind-independent) object causes both perceptions.

Possible response:

But does this really succeed in defeating the sceptical challenge? The information you hear may be equally misrepresentative of the external world as the information you see.

Idealism

“The immediate objects of perception (i.e. ordinary objects such as tables, chairs, etc.) are mind-dependent objects.”

Idealism is the view that:

- There is no external world independent of minds (so it rejects realism – both direct and indirect)

- We perceive ideas directly

In other words, the immediate objects of perception are mind-dependent ideas.

Unlike direct realism and indirect realism, idealism says there is no mind-independent external world. Instead, idealism claims that all that exists are ideas.

What’s more, idealism says that unless something is being perceived, it doesn’t exist!

Bishop Berkeley: Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous

“Esse est percipi” (to be is to be perceived)

Bishop George Berkeley (1685-1753) is the most famous proponent of idealism.

Berkeley offers various arguments against the existence of a mind-independent external world. These arguments include a variation of the sceptical argument described earlier. Berkeley asks how – if realism is true – we can link up our perception with the objects behind it. Again, it seems we can’t look past the veil of perception.

Berkeley then goes on to challenge Locke’s primary and secondary quality distinction, arguing that so-called primary qualities are equally mind-dependent as secondary qualities.

He later gives his master argument: An argument that the very idea of mind-independent objects is inconceivable and impossible.

Attack on Locke’s primary/secondary quality distinction

Berkeley argues that the only thing our senses perceive are qualities, and nothing more. For example, we perceive colours and shapes via vision, sounds via hearing, flavours via taste, and so on.

But we never perceive anything in addition to these qualities.

This claim forms the basis of one of Berkeley’s arguments against the existence of a mind-independent external world.

Earlier, we looked at Locke’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities. Recall that Locke said primary qualities are inherent in the object, whereas secondary qualities are not:

“Take away the sensation […] and all colours, tastes, odours, and sounds […] vanish and cease, and are reduced to their causes”

– Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Bk. 2, Ch. 8, §17)

Based on this extract, Locke seems to be saying that secondary qualities are mind-dependent.

Berkeley himself provides his own arguments that secondary qualities are mind dependent. For example, heat (a secondary quality) can be experienced as pain (mind-dependent). When you burn your hand on a hot fire, you don’t feel the pain and the heat separately. You feel one sensation: painful heat.

So, it seems Berkeley and Locke are in agreement so far: secondary qualities are mind dependent.

Where Berkeley disagrees with Locke is the status of primary qualities. Locke says they’re mind-independent, but Berkeley argues they’re not.

Berkeley offers various versions of perceptual variation to support the claim that primary qualities depend on the mind just as much as secondary qualities do:

- Something that looks small to me may seem large to a small animal

- Something that looks small at a distance may seem large close up

- A smooth surface may look jagged under a microscope

- An object that appears to be moving quickly to humans may appear to be moving slowly to a fly

Size, shape, and motion: they are all primary qualities but these examples show how our perception of them differs depending on the circumstances.

So, Berkeley argues, we can’t say these objects have one single size, shape, or motion independent of how it is perceived. So, primary qualities are also mind-dependent.

Bring together Berkeley’s points and we get the following argument:

- When we perceive an object, we don’t perceive anything in addition to its primary and secondary qualities

- So, everything we perceive is either a primary quality or a secondary quality

- Secondary qualities are mind-dependent

- Primary qualities are also mind-dependent

- Therefore, everything we perceive is mind-dependent

So, Berkeley uses Locke’s primary and secondary quality distinction to prove that everything we perceive is mind-dependent. This implies that there is no such thing as a mind-independent external world (and so realism is false).

The master argument

The second of Berkeley’s arguments for idealism/arguments against indirect realism is known as the master argument.

The dialogue (between Hylas and Philonous) for the master argument can be summarised as:

- P: Try to think of an object that exists independently of being perceived.

- H: OK, I am thinking of a tree that is not being perceived by anyone.

- P: But that’s impossible! You might be imagining a tree in a solitary place with no one perceiving it – but you’re still thinking about the tree. You can think of the idea of a tree, but not of a tree that exists independently of the mind.

So, Berkeley’s master argument is essentially that we cannot even conceive of a mind-independent object because as soon as we conceive of such an object, it becomes mind-dependent. Thus, mind-independent objects are impossible.

Possible response:

However, the conclusion does not necessarily follow: just because it’s impossible to have an idea of a mind-independent object, it doesn’t mean that mind-independent objects are themselves impossible.

God as the cause of perceptions

Despite arguing against the existence of a mind-independent external world, idealism does not lead to the same veil of perception problem that indirect realism does. The veil of perception disappears when we realise that the meaning of words like ‘physical object’ refer to ideas and not mind-independent objects (as realism assumes). By perceiving ideas, we are perceiving reality. That’s what reality is: ideas.

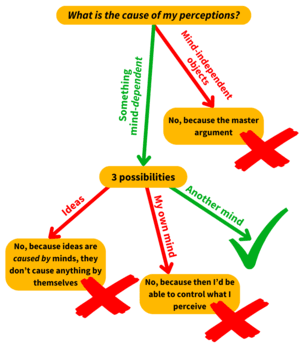

This still leaves the question of what causes these ideas. Berkeley’s answer is God, and his argument is this:

This still leaves the question of what causes these ideas. Berkeley’s answer is God, and his argument is this:

- Everything we perceive is mind-dependent (as argued above)

- There are 3 possible causes of these perceptions:

- Ideas

- My own mind

- Another mind

- It can’t be ideas (1), because ideas by themselves don’t cause anything

- It can’t be my own mind (2), because if I was the cause of my own perception then I’d be able to control what I perceived

- Therefore, the cause of my perception must be 3: another mind

- Given the complexity, variety, order, and manner of my perceptions, this other mind must be God

The role of God here resolves an obvious objection to idealism: If Berkeley’s theory is true, then presumably my desk and everything in my office no longer exist when I leave the room and stop perceiving them. So, why are they still there when I get back? Berkeley’s response is that the office (and all ‘physical objects’) constantly exist in the mind of God.

What we perceive, Berkeley says, are copies of ideas that exist eternally in God’s mind (when He wills me to perceive them). This resolves another potential criticism: We might object that when you and I both look at the same tree, we are perceiving different things – i.e. two separate ideas. However, since we are both perceiving the same copy of God’s idea, we both can be said to be perceiving the same thing.

Problems for idealism

Problems with the role of God

According to Berkeley, what we perceive are ideas that exist in God’s mind (see above). But this explanation appears to conflict with Berkeley’s conception of God.

For example, Berkeley says God doesn’t feel pain – He’s perfect. And yet I often feel and perceive pain. So, if my perception of pain is an idea in God’s mind, surely God must feel pain too? But this contradicts Berkeley’s description of God as a perfect being that doesn’t feel pain.

Berkeley’s response:

Berkeley’s response is that ideas like pain exist in God’s understanding. Although God doesn’t feel pain Himself, he understands what it is for us to feel pain. When we feel pain, it is what God actively wills us to perceive.

But we can push this objection a bit further: My perceptions constantly change from one moment to the next, and yet God is said to be unchanging. So, if my perceptions are ideas in God’s mind, and my perceptions are constantly changing, surely God must change too.

Solipsism

Solipsism is the view that one’s mind is the only thing that exists.

And Berkeley’s earlier argument – that everything one perceives is mind-dependent – suggests that there is no reason to believe anything exists beyond one’s experience. If “to be is to be perceived”, then what reason do I have to believe other people and objects exist when I’m not perceiving them, like when I’m asleep?

If idealism is true, it seems to imply that nothing exists unless I am perceiving it – that the world didn’t exist before I was born, and that the world doesn’t exist when I close my eyes or go to sleep! But this is surely absurd.

Berkeley’s response:

God exists, and He perceives everything even when I don’t.

Illusion (again)

As a direct theory of perception, idealism makes no distinction between appearance (perception) and reality.

But this makes it difficult to explain the argument from illusion that is also a problem for direct realism. For example, why does a pencil in water look crooked when it isn’t? If we perceive the pencil as crooked, Berkeley has to say the pencil is crooked – but surely this is false.

Berkeley’s response:

“He is not mistaken with regard to the ideas he actually perceives, but in the inference he makes from his present perceptions. Thus, in the case of the [pencil], what he immediately perceives by sight is certainly crooked; and so far he is in the right. But if he thence conclude that upon taking the [pencil] out of the water he shall perceive the same crookedness; or that it would affect his touch as crooked things are wont to do: in that he is mistaken.”

– Berkeley, Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous, Third Dialogue

Berkeley’s response here is to double down on the theory: If the pencil looks crooked, it is crooked. The reason we think the crooked pencil is an ‘illusion’ (i.e. a false perception) is because it misleads us about future perceptions. For example, seeing the pencil look crooked in water may deceive us that the pencil would also feel crooked. But just because we make these mistakes sometimes it doesn’t mean the so-called ‘illusion’ is any less real than the perception of the pencil as not crooked.

Hallucination (again)

However, we can push this illusion objection further: What about hallucination?

If, as Berkeley contends, “to be is to be perceived” – are we to say that hallucinations are just as real as ordinary perception? If I perceive a goblin because I took drugs, is it really plausible to say that the goblin is every bit as real as a table or a chair?

Also, why would God cause such perceptions?