Overview – Does God Exist?

A level philosophy looks at 4 arguments relating to the existence of God. These are:

There are various versions of each argument as well as numerous responses to each. The key points of each argument are summarised below:

| Ontological | Teleological | Cosmological | Problem of Evil | |

| God exists? |

Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Summary |

God must exist by definition | The universe must be designed | There must be a first cause | If God existed, there wouldn’t be evil |

| Versions | ||||

| Problems |

Ontological arguments

The ontological arguments are unique in that they are the only arguments for God’s existence that use a priori reasoning. All ontological arguments are deductive arguments.

Versions of the ontological argument aim to deduce God’s existence from the definition of God. Thus, proponents of ontological arguments claim ‘God exists’ is an analytic truth.

Anselm’s ontological argument

“Hence, even the fool is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater. […] Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.”

– St. Anselm, Proslogium, Chapter 2

Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) was the first to propose an ontological argument in his book Proslogium.

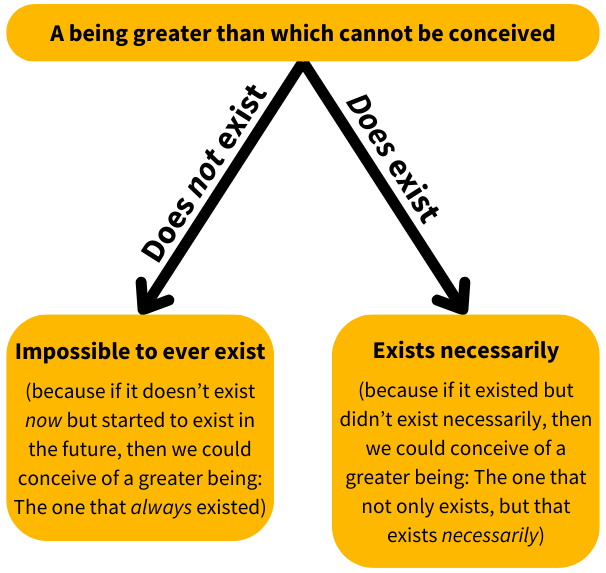

His argument can be summarised as:

- By definition, God is a being greater than which cannot be conceived

- We can coherently conceive of such a being i.e. the concept is coherent

- It is greater to exist in reality than to exist only in the mind

- Therefore, God must exist

In other words, imagine two beings:

- One is said to be maximally great in every way, but does not exist.

- The other is maximally great in every way and does exist.

Which being is greater? Presumably, the second one – because it is greater to exist in reality than in the mind.

Since God is a being that we cannot imagine to be greater, this description better fits the second option (the one that exists) than the first.

Descartes’ ontological argument

Descartes offers his own version of the ontological argument:

- I have the idea of God

- The idea of God is the idea of a supremely perfect being

- A supremely perfect being does not lack any perfection

- Existence is a perfection

- Therefore, God exists

This argument is very similar to Anselm’s, except it uses the concept of a perfect being rather than a being greater than which cannot be conceived.

Descartes argues this shows that ‘God does not exist’ is a self-contradiction. Hume uses this claim as the basis for his objection to the ontological argument.

Problems

Gaunilo’s island

Gaunilo of Marmoutiers (994-1083) argues that if Anselm’s argument is valid, then anything can be defined into existence. For example:

- The perfect island is, by definition, an island greater than which cannot be conceived

- We can coherently conceive of such an island i.e. the concept is coherent

- It is greater to exist in reality than to exist only in the mind

- Therefore, this island must exist

The conclusion of this argument is obviously false.

Gaunilo argues that if Anselm’s argument were valid, then we could define anything into existence – the perfect shoe, the perfect tree, the perfect book, etc.

Hume: ‘God does not exist’ is not a contradiction

The ontological argument reasons from the definition of God that God must exist. This would make ‘God exists’ an analytic truth (or what Hume would call a relation of ideas, as the analytic/synthetic distinction wasn’t made until years later).

The denial of an analytic truth/relation of ideas leads to a contradiction. For example, “there is a triangle with 4 sides” is a contradiction.

Contradictions cannot be coherently conceived. If you try to imagine a 4-sided triangle, you’ll either imagine a square or a triangle. The idea of a 4-sided triangle doesn’t make sense.

So, is “God does not exist” a contradiction? Descartes (and Anselm) certainly thought so.

But Hume argues against this claim. Anything we can conceive of as existent, he says, we can also conceive of as non-existent. This shows that “God exists” cannot be an analytic truth/relation of ideas, and so ontological arguments must fail somewhere.

A summary of Hume’s argument can be stated as:

- If ontological arguments succeed, ‘God does not exist’ is a contradiction

- A contradiction cannot be coherently conceived

- But ‘God does not exist’ can be coherently conceived

- Therefore, ‘God does not exist’ is not a contradiction

- Therefore, ontological arguments do not succeed

Kant: existence is not a predicate

Kant argues that existence is not a property (predicate) of things in the same way, say, green is a property of grass.

To say something exists doesn’t add anything to the concept of it.

Imagine a unicorn. Then imagine a unicorn that exists. What’s the difference between the two ideas? Nothing! Adding existence to the idea of a unicorn doesn’t make unicorns suddenly exist.

When someone says “God exists”, they don’t mean “there is a God and he has the property of existence”. If they did, then when someone says “God does not exist”, they’d mean, “there is a God and he has the property of non existence” – which doesn’t make sense!

Instead, what people mean when they say “God exists” is that “God exists in the world”. This cannot be argued from the definition of God and could only be proved via (a posteriori) experience. Thus the ontological argument fails to prove God’s (actual) existence.

Norman Malcolm’s ontological argument

Kant’s objection to the ontological argument is generally considered to be the most powerful argument against it.

So, in response, some philosophers have developed alternate versions that avoid this criticism.

Malcolm accepts that Descartes and Anselm (at least as presented above) are wrong.

Instead, Malcolm argues that it’s not existence that is a perfection, but the logical impossibility of non-existence (necessary existence, in other words).

This (necessary existence) is a predicate, so avoids Kant’s argument above. Malcolm’s ontological argument is as follows:

- Either God exists or does not exist

- God cannot come into existence or go out of existence

- If God exists, God cannot cease to exist

- Therefore, if God exists, God’s existence is necessary

- Therefore, if God does not exist, God’s existence is impossible

- Therefore, God’s existence is either necessary or impossible

- God’s existence is impossible only if the concept of God is self-contradictory

- The concept of God is not self-contradictory

- Therefore, God’s existence is not impossible

- Therefore, God exists necessarily

Malcolm’s argument essentially boils down to:

- God’s existence is either necessary or impossible (see above)

- God’s existence is not impossible

- Therefore God’s existence is necessary

Possible response:

We may respond to point 8, as discussed in the concept of God section, that the concept of God is self-contradictory.

Alternatively, we may argue that the meaning of “necessary” changes between premise 4 and the conclusion (10) and thus Malcolm’s argument is invalid. In premise 4, Malcolm is talking about necessary existence in the sense of a property that something does or does not have. By the conclusion, Malcolm is talking about necessary existence in the sense that it is a necessary truth that God exists. But this is not the same thing. We can accept that if God exists, then God has the property of necessary existence, but deny the conclusion that God exists necessarily.

Teleological arguments

The teleological arguments are also known as arguments from design.

These arguments aim to show that certain features of nature or the laws of nature are so perfect that they must have been designed by a designer – God.

Hume’s teleological argument

In Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Hume considers a version of the teleological argument (through the character Cleanthes), which he goes on to reject (through the character of Philo).

“The intricate fitting of means to ends throughout all nature is just like (though more wonderful than) the fitting of means to ends in things that have been produced by us – products of human designs, thought, wisdom, and intelligence. Since the effects resemble each other, we are led to infer by all the rules of analogy that the causes are also alike, and that the author of nature is somewhat similar to the mind of man, though he has much larger faculties to go with the grandeur of the work he has carried out. By this argument… we prove both that there is a God and that he resembles human mind and intelligence.”

– Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Part 5

Hume’s argument here draws an analogy between things designed by humans and nature:

- The ‘fitting of means to ends’ in human design (e.g. the fitting of the many parts of a watch to achieve the end of telling the time) resemble the ‘fitting of means to ends’ in nature (e.g. the many parts of a human’s eye to achieve the end of seeing things)

- Similar effects have similar causes

- The causes of human designs (e.g. watches) are minds

- So, by analogy, the cause of design in nature is also a mind

- And, given the ‘grandeur of the work’ of nature, this other mind is God.

William Paley: Natural Theology

William Paley (1743-1805) wasn’t the first to propose a teleological argument for the existence of God, but his version is perhaps the most famous.

Paley compares man-made objects, such as a watch, with certain aspects of nature, such as a stone. If you found a stone in a field, you might assume it had just been there forever. But that explanation doesn’t work for the watch.

Paley compares man-made objects, such as a watch, with certain aspects of nature, such as a stone. If you found a stone in a field, you might assume it had just been there forever. But that explanation doesn’t work for the watch.

The reason for this is that a watch, unlike the stone, has many parts organised for a purpose. Paley says this is the hallmark of design:

“When we come to inspect the watch, we perceive (what we could not discover in the stone) that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g. that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day.”

– William Paley, Natural Theology, Chapter 1

Nature and aspects of nature, such as the human eye, are composed of many parts. These parts are organised for a purpose – in the case of the eye, to see.

So, like the watch, nature has the hallmarks of design – but “with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater and more”. And for something to be designed, it must have an equally impressive designer.

Paley says this designer is God.

Problems

Hume: problems with the analogy

Hume (as the character Philo) points out various problems with the analogy between the design of human-made objects and nature, such as:

- We can observe human-made items being designed by minds, but we have no such experience of this in the case of nature. Instead, designs in nature could be the result of natural processes (what Philo calls ‘generation and vegetation’).

- The analogy focuses on specific aspects of nature that appear to be designed (e.g. the human eye) and generalises this to the conclusion that the whole universe must be designed.

- Human machines (e.g. watches and cars) obviously have a designer and a purpose. But biological things (e.g. an animal or a plant, such as a cabbage) do not have an obvious purpose or designer – they appear to be the result of an unconscious process of ‘generation and vegetation’. The universe is more like the latter (i.e. a biological thing) than the former (i.e. a machine) and so, by analogy, the cause of the universe is better explained by this unconscious processes of ‘generation and vegetation’ rather than the conscious design of a mind.

An argument from analogy is only as strong as the similarities between the two things being compared (nature and human designs). These differences weaken the jump from human-made items being designed to the whole universe being designed.

Hume: Spatial disorder

Hume (as the character Philo) argues that although there are examples of order within nature (which suggests design), there is also much “vice and misery and disorder” in the world (which is evidence against design).

If God really did design the world, Hume argues, there wouldn’t be such disorder. For example:

- There are huge areas of the universe that are empty, or just filled with random rocks or are otherwise uninhabitable. This suggests that the universe isn’t designed but instead we just happen, by coincidence, to be in a part that has spatial order.

- Some parts of the world (e.g. droughts, hurricanes, etc.) go wrong and cause chaos. Hume argues that if the world is designed, these chaotic features suggest that the designer isn’t very good.

- Animals have bodies that feel pain and that could have been made in such ways that they could have happier lives. If God designed animals and humans, you would expect He would make animals and humans in this way so that their lives would be easier and happier.

These features are examples of spatial disorder – features that wouldn’t make sense to include if you designed the universe.

Hume argues that such examples of disorder show that the universe isn’t designed. Or, if the universe is designed, then the designer is neither omnipotent nor omnibenevolent (as God is claimed to be).

Hume: causation

Hume famously argues that we never experience causation – only the ‘constant conjunction’ of one event following another. If this happens enough times, we infer that A causes B.

For example, experience (ever since you were a baby) tells you that if one snooker ball hits another (A), the second snooker ball will move (B). You don’t actually experience A causing B, but it’s reasonable to expect this relationship to hold in the future because you’ve seen it and similar examples hundreds of times.

But imagine that you take a sip of tea and at the same time your friend coughs. Would it be reasonable to infer that drinking the tea caused your friend to cough based on this one instance? Obviously not. The point is: You cannot infer causation from a single instance.

Applying this to teleological arguments, Hume (as the character Philo) argues that the creation of the universe was a unique event – we only have experience of this one universe. And so, like the tea example, we can’t infer a causal relationship between designer and creation based on just one instance.

Hume: finite matter, infinite time

“Instead of supposing matter to be infinite, as Epicurus did, let us suppose it to be finite and also suppose space to be finite, while still supposing time to be infinite. A finite number of particles in a finite space can have only a finite number of transpositions; and in an infinitely long period of time every possible order or position of particles must occur an infinite number of times.”

– Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Part 8

Hume’s objection here assumes the following:

- Time is infinite

- Matter is finite

Given these assumptions, it is inevitable that matter will organise itself into combinations that appear to be designed.

It’s a bit like the monkeys and typewriters thought experiment:

Given an infinite amount of time, a monkey will eventually type the complete works of Shakespeare.

The point here is not that the monkey would learn to write Shakespeare – or even that it would understand what it had written. The point is that, given an infinite amount of time, the monkey would eventually type everything.

The point here is not that the monkey would learn to write Shakespeare – or even that it would understand what it had written. The point is that, given an infinite amount of time, the monkey would eventually type everything.

This is the nature of infinity. It’s inevitable that the monkey will write something that appears to be intelligent, even though it’s just hitting letters at random.

The same principle applies to the teleological argument, argues Hume: Given enough time, it is inevitable that matter will arrange itself into combinations that appear to be designed, even though they’re not.

Darwin: evolution by natural selection

Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) theory of evolution by natural selection explains how complex organisms – complete with parts organised for a purpose – can emerge from nature without a designer.

For example, it may seem that God designed giraffes to have long necks so they could reach leaves in high trees. But the long necks of giraffes can be explained without a designer, for example:

- Competition for food is tough

- An animal that cannot acquire enough food will die before it can breed and produce offspring

- An animal with a (random genetic mutation for a) neck that’s 1cm longer than everyone else’s will be able to access 1cm more food

- This competitive advantage makes it more likely to survive and produce offspring

- The offspring are likely to inherit the gene for a longer neck, making them more likely to survive and reproduce as well

- Longer necked-animals become more common as a result

- The environment becomes more competitive as more and more animals can reach the 1cm higher leaves

- An animal with a neck 2cm longer has the advantage in this newly competitive environment

- Repeat process over hundreds of millions of years until you have modern day giraffes

The key idea is that – given enough time and genetic mutations – it is inevitable that animals and plants will adapt to their environment, thus creating the appearance of design.

This directly undermines Paley’s claim that anything that has parts organised to serve a purpose must be designed.

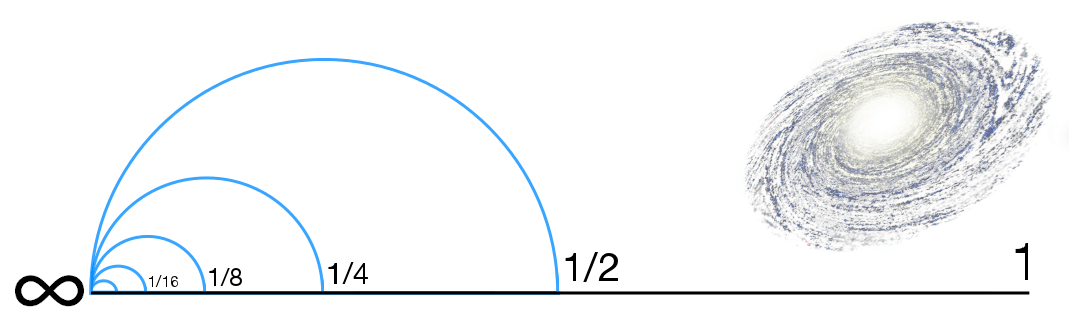

Swinburne: The Argument from Design

Swinburne’s version of the teleological argument distinguishes between:

- Examples of order in nature (spatial order)

- And the order of the laws of nature (temporal order)

Swinburne accepts that science, for example evolution, can explain the apparent design of things like the human eye (i.e. spatial order) and so Paley’s teleological argument does not succeed in proving God’s existence. However, Swinburne argues, we can’t explain the laws of nature (i.e. temporal order) in the same way.

For example, the law of gravity is such that it allows galaxies to form, and planets to form within these galaxies, and life to form on these planets. But if gravity had the opposite effect – it repelled matter, say – then life would never be able to form. If gravity was even slightly stronger, planets wouldn’t be able to form. So how do we explain why these laws are the way they are?

Unlike spatial order, we can’t give a scientific explanation of why the laws of nature are as they are. Science can explain and predict things using these laws – but it has to first assume these laws. Science can’t explain why these laws are the way they are. In the absence of a scientific explanation of the laws of nature, Swinburne argues, the best explanation of temporal order is a personal explanation.

We give personal explanations of things all the time – for example, ‘this sentence exists because I chose to write it’ or ‘that building exists because someone designed and built it’. Swinburne argues that, by analogy, we can explain the laws of nature (i.e. temporal order) in a similarly personal way: The laws of nature are the way they are because someone designed them.

In the absence of a scientific explanation of temporal order, Swinburne argues, the best explanation is the personal one: The laws of nature were designed by God.

Problems

Multiple universes

Hume’s earlier argument (finite matter, infinite time) can be adapted to respond to Swinburne’s teleological argument.

But instead of arguing that time is infinite, as Hume does, we could argue that the number of universes is infinite.

This idea of multiple universes is popular among some physicists, as it explains various phenomena in quantum mechanics.

But anyway, if there are an infinite number of universes (or even just a large enough number), it is likely that some of these universes will have laws of nature (temporal order) that support the formation of life. Of course, when such universes do exist, it is just sheer luck. If each universe has randomly different scientific laws, there will also be many universes where the temporal order does not support life.

Is the designer God?

Both Hume and Kant have argued that even if the teleological argument succeeded in proving the existence of a designer, this designer would not necessarily be God (as defined in the Concept of God section).

For example:

- God’s power is supposedly infinite (omnipotence), yet the universe is not infinite

- Designers are not always creators. Designer and creator might be two separate people (e.g. the guy who designs a car doesn’t physically build it)

- The design of the universe may be the result of many small improvements by many people

- Designers can die even if their creations live on. How do we know the designer is eternal, as God is supposed to be?

Cosmological arguments

Cosmological arguments start from the observation that everything depends on something else for its existence. For example, you depended on your parents in order to exist, and they depended on their parents, and so on. Cosmological arguments then apply this to the existence of the universe itself. The argument is that the universe depends on something else to exist: God.

The Kalam Argument

The Kalam argument is perhaps the simplest version of the cosmological argument in the A level philosophy syllabus. It says:

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause

- The universe began to exist

- Therefore, the universe has a cause

Aquinas: Five Ways

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) gave five different versions of the cosmological argument. A level philosophy requires you to know these three:

Argument from motion

Aquinas’ first way is the argument from motion.

“It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion… It is [impossible that something] should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover… Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.”

– Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Part 1 Question 3

A summary of this argument:

- Some things in the world are in motion

- E.g. a football rolling along the ground

- Things can’t move themselves, so whatever is in motion must have been put in motion by something else

- E.g. someone kicked the ball

- If A is put in motion by B, then something else (C) must have put B in motion, and so on

- If this chain goes on infinitely, then there is no first mover

- If there is no first mover, then there is no other mover, and so nothing would be in motion

- But things are in motion

- Therefore, there must be a first mover

- The first mover is God

Argument from causation

Aquinas’ second way – the argument from causation – is basically the same as the argument from motion, except it talks about a first cause rather than a first mover:

- Everything in the universe is subject to cause and effect

- E.g. throwing a rock caused the window to smash

- C is caused by B, and B is caused by A, and so on

- If this chain of causation was infinite, there would be no first cause

- If there were no first cause, there would be no subsequent causes or effects

- But there are causes and effects in the world

- Therefore, there must have been a first cause

- The first cause is God

Argument from contingency

Aquinas’ third way relies on a distinction between necessary and contingent existence. It’s a similar distinction to necessary and contingent truth from the epistemology module.

Things that exist contingently are things that might not have existed.

For example, the tree in the field wouldn’t exist if someone hadn’t planted the seed years ago. So, the tree exists contingently. Its existence is contingent on someone planting the seed.

So, using this idea of contingent existence, Aquinas argues that:

- Everything that exists contingently did not exist at some point

- If everything exists contingently, then at some point nothing existed

- If nothing existed, then nothing could begin to exist

- But since things did begin to exist, there was never nothing in existence

- Therefore, there must be something that does not exist contingently, but that exists necessarily

- This necessary being is God

Descartes’ Cosmological Argument

Descartes’ version of the cosmological argument is a lot more long-winded than the Kalam argument or any of Aquinas’.

The key points are along these lines:

- I can’t be the cause of my own existence because if I was I would have given myself all perfections (e.g. omnipotence, omniscience, etc.)

- I depend on something else to exist

- I am a thinking thing and have the idea of God

- Whatever caused me to exist must also be a thinking thing that has the idea of God

- Whatever caused me to exist must either be the cause of its own existence or caused by something else

- If it was caused by something else then this something else must also either be the cause of its own existence or caused by something else

- There cannot be an infinite chain of causes

- So there must be something that caused its own existence

- Whatever causes its own existence is God

There’s a bit more to Descartes’ version than this. For example, he talks about a cause needed to keep him in existence and how there must be ‘as much reality’ in the cause as in the effect. But the points above constitute the main argument.

Leibniz: Sufficient reason

Note: This is another cosmological argument from contingency, like Aquinas’ third way above

Leibniz’s argument is premised on his principle of sufficient reason. The principle of sufficient reason says that every truth has an explanation of why it is the case (even if we can’t know this explanation).

Leibniz then defines two different types of truth:

- Truths of reasoning: this is basically another word for necessary or analytic truths

- Truths of fact: this is basically another word for contingent or synthetic truths

The sufficient reason for truths of reasoning (i.e. analytic truths) is revealed by analysis. When you analyse and understand “3+3=6”, for example, you don’t need a further explanation why it is true.

But it is more difficult to provide sufficient reason for truths of fact (i.e. contingent truths) because you can always provide more detail via more contingent truths. For example, you can explain the existence of a tree by saying someone planted a seed. But you could then ask why the person planted the seed, or why seeds exist in the first place, or why the laws of physics are the way they are, and so on. This process of providing contingent reasons for contingent facts goes on forever.

“Therefore, the sufficient or ultimate reason must needs be outside of the sequence or series of these details of contingencies, however infinite they may be.”

– Leibniz, Monadology, Section 37

So, to escape this endless cycle of contingent facts and provide sufficient reason for truths of fact (i.e. contingent truths), we need to step outside the sequence of contingent facts and appeal to a necessary substance. This necessary substance is God, Leibniz says.

Problems

Is a first cause necessary?

Most of the cosmological arguments assume something along the lines of ‘there can’t be an infinite chain of causes’ (except the cosmological arguments from contingency). For example, they say stuff like there must have been a first cause or a prime mover.

But we can respond by rejecting this claim. Why must there be a first cause? Perhaps there is just be an infinite chain of causes stretching back forever.

Possible response:

- An infinite chain of causes would mean an infinite amount of time has passed prior to the present moment

- If an infinite amount of time has passed, then the universe can’t get any older (because infinity + 1 = infinity)

- But the universe is getting older (e.g. the universe is a year older in 2020 than it was in 2019)

- Therefore an infinite amount of time has not passed

- Therefore there is not an infinite chain of causes

Hume’s objections to causation

Another assumption (or premise) of many of the cosmological arguments above (not so much the contingency ones) is something like ‘everything has a cause’.

But Hume’s fork can be used to question this claim that ‘everything has a cause’:

- Relation of ideas: ‘Everything has a cause’ is not a relation of ideas because we can conceive of something without a cause. For example, we can imagine a chair that just springs into existence for no reason – it’s a weird idea, but it’s not a logical contradiction like a 4-sided triangle or a married bachelor.

- Matter of fact: ‘Everything has a cause’ cannot be known as a matter of fact either, says Hume. We never actually experience causation – we just see event A happen and then event B happen after. Even if we see B follow A a million times, we never experience A causing B, just the ‘constant conjunction’ of A and B.

Further, in the specific case of the creation of the universe, we only ever experience event B (i.e. the continued existence of the universe) and never what came before (i.e. the thing that caused the universe to exist).

This all casts doubt on the premise of cosmological arguments that ‘everything has a cause’.

Russell: Fallacy of composition

Bertrand Russell argues that cosmological arguments fall foul of the fallacy of composition. The fallacy of composition is an invalid inference that because parts of something have a certain property, the entire thing must also have this property. Examples:

- Just because all the players on a football team are good, this doesn’t guarantee the team is good. For example, the players might not work well together.

- Just because a sheet of paper is thin, it doesn’t mean things made from sheets of paper are thin. For example, a book with enough sheets of paper can be thick.

Applying this to the cosmological argument, we can raise a similar objection to Hume’s above: just because everything within the universe has a cause, doesn’t guarantee that the universe itself has a cause.

Or, to apply it to Leibniz’s cosmological argument: just because everything within the universe requires sufficient reason to explain its existence, doesn’t mean the universe itself requires sufficient reason to explain its existence. Russell says: “the universe is just there, and that’s all.”

Possible response:

- Ok, but everything within the universe exists contingently

- And if everything within the universe didn’t exist, then the universe itself wouldn’t exist either (because that’s all the universe is: the collection of things that make it up)

- So the universe itself exists contingently, not just the stuff within it

- And so the universe itself requires sufficient reason to explain its existence

Is the first cause God?

Aquinas’ first and second ways and the Kalam argument only show that there is a first cause. But they don’t show that this first cause is God.

So, even if we accept that there was a first cause, it doesn’t necessarily follow that God exists – much less the specific being described in the concept of God.

So, even if the cosmological argument is sound, it doesn’t necessarily follow that God exists.

Possible response:

This objection doesn’t work so well against Descartes’ version because he specifically reasons that there is a first cause and that this first cause is an omnipotent and omniscient God.

Similarly, you could argue that any being that exists necessarily (such as follows from Aquinas’ third way and Leibniz’s cosmological argument) would be God.

The problem of evil

The problem of evil uses the existence of evil in the world to argue that God (as defined in the concept of God) does not exist.

These arguments can be divided into two forms:

- The logical problem of evil is a deductive argument that says the existence of God is logically impossible given the existence of evil in the world

- The evidential problem of evil is an inductive argument which says that, while it is logically possible that God exists, the amount of evil and unfair ways it is distributed in our world is pretty strong evidence that God doesn’t exist

And evil can be divided into two types of evil:

| Moral evil | Natural evil |

| Evil acts committed by people | Suffering as a result of natural processes |

| E.g. torture, murder, genocide, etc. | E.g. earthquakes, tsunamis, volcano eruptions, etc. |

One final definition: a theodicy is an explanation of why an omnipotent and omniscient God would permit evil.

The logical problem of evil

“Epicurus’s old questions have still not been answered. Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then where does evil come from?”

– Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Part 10

J.L. Mackie: Evil and Omnipotence

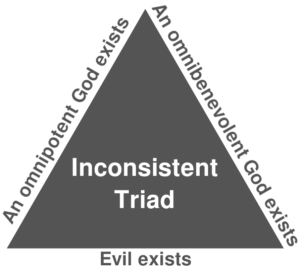

Inconsistent triad

The simple version of Mackie’s argument is that the following statements are logically inconsistent – i.e. one or more of them contradict each other:

- God is omnipotent

- God is omnibenevolent

- Evil exists

Mackie’s argument is that, logically, a maximum of 2 of these 3 statements can be true but not all 3. This is sometimes referred to as the inconsistent triad.

He argues that if God is omnibenevolent then he wants to stop evil. And if God is omnipotent, then he’s powerful enough to prevent evil.

But evil does exist in the world. People steal, get murdered, and so on. So either God isn’t powerful enough to stop evil, doesn’t want to stop evil, or both.

In the concept of God, God is defined as an omnipotent and omnibenevolent being. If such a being existed, argues Mackie, then evil would not exist. But evil does exist. Therefore, there is no omnipotent and omnibenevolent being. Therefore, God does not exist.

Reply 1: good couldn’t exist without evil

People often make claims like “you can’t appreciate the good times without experiencing some bad times”.

This is basically what this reply says: without evil, good couldn’t exist.

Mackie questions whether this statement is true at all. Why can’t we have good without evil?

Imagine if we lived in a world where everything was red. Presumably, we wouldn’t have created a word for ‘red’, nor would we know what it meant if someone tried to explain it to us. But it would still be the case that everything is red, we just wouldn’t know.

It’s a similar story with good and evil.

God could have created a world in which there was no evil. Like the red example, we wouldn’t have the concept of evil. But it would still be the case that everything is good – we just wouldn’t be aware of it.

Reply 2: the world is better with some evil than none at all

You could develop reply 1 above to argue that some evil is necessary for certain types of good. For example, you couldn’t be courageous (good) without having to overcome fear of pain, death, etc. (evil).

We can define first and second order goods:

- First order good: e.g. pleasure

- Second order good: e.g. courage

The argument is that second order goods seek to maximise first order goods. And second order goods are more valuable than first order goods. But without first order evils, second order goods couldn’t exist.

Let’s say we accept that first order evil is necessary for second order good to exist. How do you explain second order evil?

Second order evils seek to maximise first order evils such as pain. So, for example, malevolence or cruelty are examples of second order evils.

But we could still have a world in which people were courageous (second order good) in overcoming pain (first order evil) without these second order evils. So why would an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God allow the existence of second order evils if there is no greater good in doing so?

Reply 3: we need evil for free will

We can develop the second order evil argument above further and argue that second order evil is necessary for free will. And free will is inherently such a good and valuable thing that it outweighs the bad that results from people abusing free will to do evil things.

So, while allowing free will brings some suffering, the net good of having free will is greater than if we didn’t. Therefore, it’s logically possible that an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow evil (both first order and second order) for the greater good of free will.

- An omnipotent God can create any logically possible world

- If it’s logically possible to freely choose to act in a way that’s good on one occasion, then it’s logically possible to freely choose to act in a way that’s good on every occasion

- So, an omnipotent God could create a world in which everyone freely chooses to act in a way that’s good

In other words, there is a logically possible world with both free will and without second order evils.

This, surely, would be the best of both worlds and maximise good most effectively: you would have second order goods, plus the good of free will, but without second order evils. This is a logically possible world – the logically possible world with the most good.

So, why wouldn’t an omnipotent and omniscient God create this specific world? Second order evils do not seem logically necessary, and yet they exist.

Problems

Alvin Plantinga: God, Freedom and Evil

Plantinga argues that we don’t need a plausible theodicy to defeat the logical problem of evil. All we need to show is that the existence of evil is not logically inconsistent with an omnipotent and omnibelevolent God.

So, even if the explanation of why God would allow evil doesn’t seem particularly plausible, as long as it’s a logical possibility then we have defeated the logical problem of evil.

Free will defence

Even Mackie himself admits that God’s existence is not logically incompatible with some evil (first order evil). But his argument is that second order evil isn’t necessary.

Plantinga argues, however, that it’s logically possible (which is all we need to show to defeat the logical problem of evil) that God would allow second order evil for a greater good. His argument is as follows:

- A morally significant action is one that is either morally good or morally bad

- A being that is significantly free is one that is able to do or not do morally significant actions

- A being created by God to only do morally good actions would not be significantly free

- So, the only way God could eliminate evil (including second order evil) would be to eliminate significantly free beings

- But a world that contains significantly free beings is more good than a world that does not contain significantly free beings

In short, this argument shows that it’s at least logically possible that God would allow second order evil for the greater good of significant freedom.

Perhaps God could have created the world where everyone chose to only do morally good actions (as Mackie describes above) – but such a world wouldn’t be significantly free. Free will is inherently good and so significant free will could outweigh the negative of people using that significant free will to commit second order evils.

Natural evil as a form of moral evil

The free will defence above explains why an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow moral evil. But it doesn’t explain natural evil.

When innocent people are killed in natural disasters, it doesn’t seem this is the result of free will. So, even if an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow moral evil, why does this kind of evil exist as well?

Plantinga argues that it’s possible natural evil is the result of non-human actors such as Satan, fallen angels, demons, etc. This would make natural evil another form of moral evil, the existence of which would be explained by free will.

Even if this doesn’t sound very plausible, it’s at least possible. And remember, Plantinga’s argument is that we only need to show evil is not logically inconsistent with God’s existence to defeat the logical problem of evil.

The evidential problem of evil

Unlike the logical problem of evil, the evidential problem of evil can allow that God’s existence is possible.

However, it argues the amount and distribution of evil in the world provides good evidence that God probably doesn’t exist.

For example:

- Innocent babies born with painful congenital diseases

- The sheer number of people currently living in slavery, extreme poverty or fear

- The millions of innocent and anonymous people throughout history killed for no good reason

We can reject the logical problem of evil and accept that God would allow some evil. But would an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God allow so much evil? And to people so undeserving of it?

The evidential problem of evil argues that if God did exist, there would be less evil and it would be less concentrated among those undeserving of it.

Problems

Free will (again)

Sure, God could have made a world with less evil. But this would mean less free will. And on balance, having free will creates more good than the evil it also creates.

Possible response:

OK, maybe God would allow some evil for the greater good of free will. But it seems possible – simple, even – that God could have created a world with less evil than our world without sacrificing the greater good of free will.

For example, our world exactly as it is, with the same amount of free will, but with 1% less cancer. God could have created this world, so why didn’t He?

The evidential problem of evil could insist that the amount of evil – or unfair ways it is distributed – could easily be reduced without sacrificing some greater good, and so it seems unlikely that God exists, in this world, given this particular distribution of evil.

John Hick: Evil and the God of Love

Soul making

Hick argues that humans are unfinished beings. Part of our purpose in life is to develop personally, ethically and spiritually – he calls this ‘soul making’.

As discussed above, it would be impossible for people to display (second order) virtues such as courage without fear of (first order) evils such as pain or death. Similarly, we couldn’t learn virtues such as forgiveness if people never treated us wrongly.

Of course, God could just have given us these virtues right off the bat. But, Hick says, virtues acquired through hard work and discipline are “good in a richer and more valuable sense”. Plus, there are some virtues, such as a genuine and authentic love of God, that cannot simply be given (otherwise they wouldn’t be genuine).

This explanation goes some way towards explaining why God would allow the amount and distribution of evil we see. He then addresses some specific examples of evils that may not seem to fit with an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God:

Why God allows animals to suffer

The evidential problem of evil can ask Hick why God would allow animals to suffer when there is no benefit. After all, they can’t develop spiritually like we can.

Hick’s response is that God wanted to create epistemic distance between himself and humanity – i.e. a world in which his existence could be doubted. If God just proved he existed, we wouldn’t be free to develop a relationship with him.

Why God allows such terrible evils

Hick argues that it’s not possible for God to just get rid of terrible evil – e.g. baby torture – and leave only ordinary evil. The reason for this is that terrible evils are only terrible in contrast to ordinary evils. So, if God did get rid of terrible evils, then the worst ordinary evils would become the new terrible evils. If God kept getting rid of terrible evils then he would have to keep reducing free will and thus the development of personal and spiritual virtues (soul making).

Why God allows such pointless evils

Hick argues that pointless evils – e.g. anonymously dying in vain trying to save someone – are somewhat of a mystery. However, if every time we saw someone suffering we knew it was for some higher purpose (i.e. it wasn’t pointless), then we would never be able to develop deep sympathy.

Again, this goes back to the soul making theodicy: without seemingly unfair and pointless evil, we would never be able to develop virtues such as hope and faith – both of which require a degree of uncertainty.