Overview – Metaethics

A level metaethics is about what moral judgements – e.g. “murder is wrong” – mean and what (if anything) makes them true or false.

The main debate is about whether mind-independent moral properties exist or not:

- Moral realism: There are mind-independent, external moral properties and facts – e.g. “murder is wrong” is a moral fact because the act of murder has the moral property of wrongness

- Moral anti-realism: Mind-independent moral properties and facts do not exist.

But there is also a second – related – debate about what moral judgements mean:

- Cognitivism: Moral judgements express cognitive mental states – i.e. beliefs, aim to describe reality, and can be true or false

- E.g. “Murder is wrong”

- Non-cognitivism: Moral judgements express non-cognitive mental states, do not aim to describe reality, and are not capable of being true or false

- E.g. “Boo! Murder!” or “Don’t torture animals!”

(cognitivism/non-cognitivism also crops up in religious language as well as moral language).

You’ve also got 5 specific metaethical theories, that can be divided up according to the two categories above:

| Moral realism | Moral anti-realism | |

| Cognitivism | ||

| Non-cognitivism |

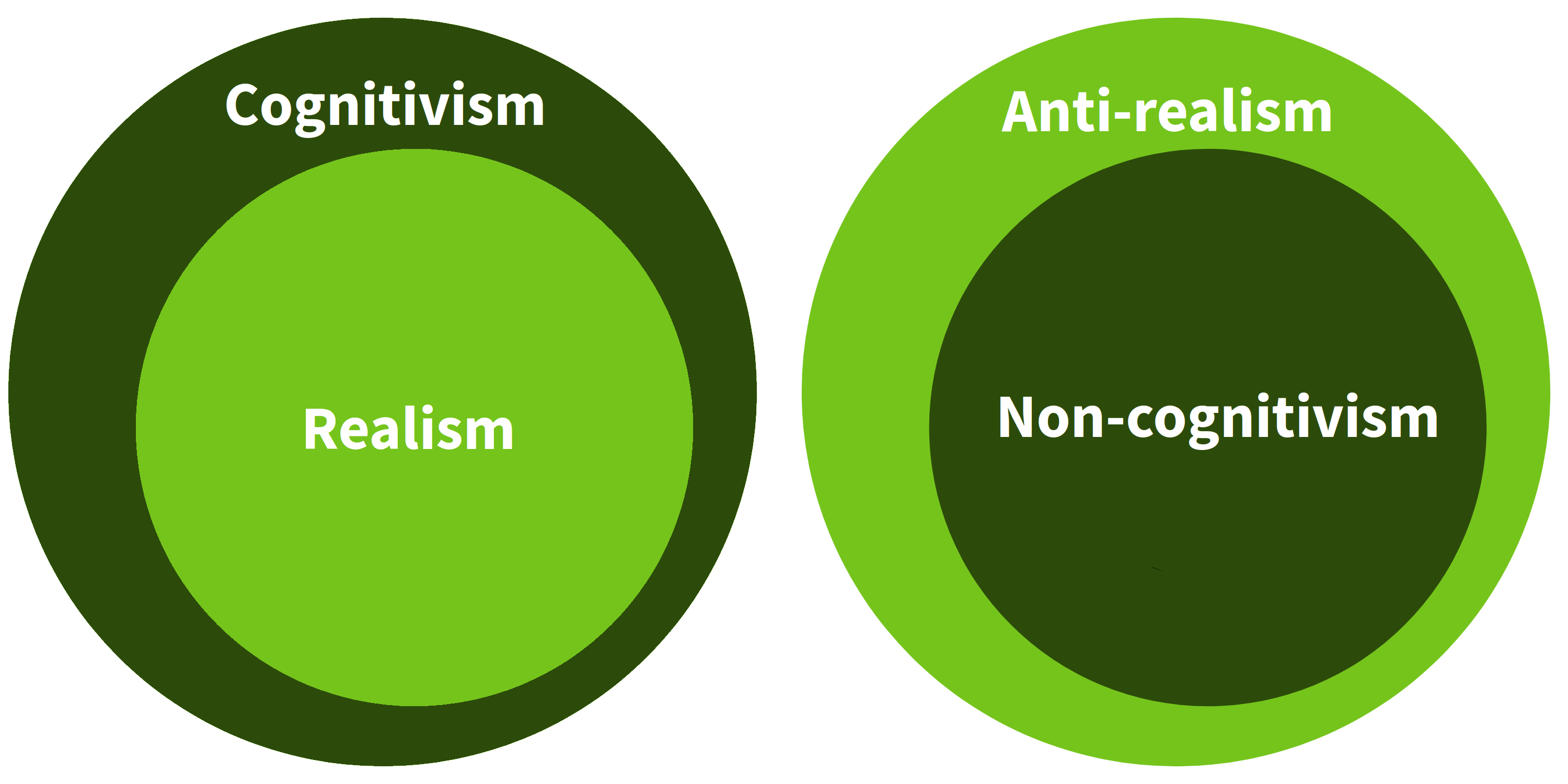

Having these two sets of categories (realism/anti-realism and cognitivism/non-cognitivism) can make it a bit confusing because there is overlap between the categories. For example, all non-cognitivist theories are anti-realist theories but not all cognitivist theories are realist theories.

So, it’s important to be clear on the differences between what the categories are about:

- Realism/anti-realism is about whether or not mind-independent moral properties exist

- Cognitivism/non-cognitivism is about what people mean when they make moral judgements

The theories are linked with each other to some degree. For example, the arguments against naturalism are the same arguments in favour of non-naturalism, and the arguments against non-naturalism are the same arguments in favour of error theory.

Realist theories

Realist metaethical theories argue that mind-independent moral properties – such as ‘right’, ‘wrong’, ‘good’, and ‘bad’ – exist.

These moral properties give rise to moral facts, such as “murder is wrong”. A realist would say murder has the property of wrongness in the same way grass has the property of greenness.

But there is disagreement among realists as to what these mind-independent moral properties actually are:

- Ethical naturalism says moral properties are natural properties

- Ethical non-naturalism says moral properties are non-natural properties

Both ethical naturalism and ethical non-naturalism are cognitivist theories: they agree that moral judgements express beliefs that are capable of being true or false.

Ethical naturalism

Ethical naturalism says that moral judgements are beliefs that are intended to be true or false (cognitivism) and that moral properties exist (realism) and are natural properties.

So, according to ethical naturalism, “murder is wrong” expresses a cognitive belief that murder is wrong – where ‘wrong’ refers to a natural property.

Utilitarianism as naturalism

Utilitarianism is perhaps the obvious example of a naturalist ethical theory. It says ‘good’ can be reduced to pleasure, and ‘bad’ can be reduced to pain. Pain and pleasure are natural properties of the mind/brain and so utilitarianism is a naturalist theory.

Mill’s ‘proof’ of utilitarianism

John Stuart Mill argues that happiness is not only good, it is the only good. Other things we desire – such as truth and freedom – are part of what happiness is to us. Mill provides the following metaethical argument for utilitarianism:

- The only proof that something is desirable is that people desire it

- No proof can be given why the general happiness is desirable other than that each person desires their own happiness

- This desirability is “all the proof the case admits of” that happiness is a good thing

- All our other values (e.g. truth, freedom, dignity) constitute what makes us happy

- In other words, the reason we value these things is because they make us happy

- So, not only is happiness good, it is the only good

Virtue ethics as naturalism

Although utilitarianism is the obvious form of moral naturalism, some philosophers see virtue ethics as a form of moral naturalism too.

For example, Aristotle’s discussion of ergon/function can be interpreted as a discussion of natural facts about human beings. We might argue that it is a natural fact that the function of human beings is to use reason – in the same way it is a natural fact that the function of a knife is to cut things. There is nothing spooky or non-natural about claiming that the function of a knife is to cut things and likewise there is nothing spooky or non-natural about claiming that the function of human beings is to use reason.

So, on this reading, ‘good’ reduces to a set of natural facts about function and performing that function well. For example, being courageous is good because being courageous helps humans act correctly according to reason.

Problems for ethical naturalism:

- The naturalistic fallacy (see non-naturalism)

- The is-ought problem (see emotivism)

- The verification principle (see emotivism)

Ethical non-naturalism

Ethical non-naturalism says that moral judgements are beliefs that are intended to be true or false (cognitivism) and that moral properties exist (realism) but are non-natural properties.

So, according to ethical non-naturalism, “murder is wrong” expresses a cognitive belief that murder is wrong – where ‘wrong’ refers to a non-natural property.

One way to think about non-natural properties is as non-physical properties. These non-natural moral properties cannot be reduced to anything simpler. They are basic.

G.E. Moore: Principia Ethica

The naturalistic fallacy

Moore’s book begins with criticisms of ethical naturalism (specifically utilitarian naturalism).

He invents the term ‘naturalistic fallacy’ to describe the fallacy (i.e. bad reasoning) of equating goodness with some natural property (such as pleasure or pain). For example, Moore would say it is a fallacy to conclude that drinking beer is good from the fact that drinking beer is pleasurable because they are two completely different kinds of properties – one moral, one natural. Even if pleasure and goodness are closely correlated, it doesn’t and could not follow that they are the same thing. So, Moore would argue that Mill’s proof of utilitarianism is invalid: To conclude that happiness (a natural property) is good (a moral property) commits the naturalistic fallacy.

Moore’s argument here – that you can’t logically jump from natural to moral – is very similar to Hume’s is/ought gap.

The open question argument

Moore further argues that it is an open question whether ‘pleasure’ and ‘good’ are the same thing:

- Closed question: “Is good good?” or “is pleasure pleasure?”

- Open question: “Is pleasure good?

But Moore argues that if goodness and pleasure really were the same thing (as naturalism claims), it would be a closed question to ask “is pleasure good?”. In other words, Moore is arguing that if naturalism was true and ‘good’ meant the same thing as ‘pleasure’, it wouldn’t make sense to ask “is pleasure good?” because it would be like asking “is pleasure pleasure?”.

Possible reply:

It doesn’t seem to follow that because “is pleasure good?” is an open question, pleasure and good cannot be the same thing. After all, there are plenty of examples where two things are in fact the same thing but it is still an open question whether they are.

For example, ‘water’ and ‘H2O’ refer to the same thing, but it is still an open question to ask “is water H2O?” So, it’s possible that ‘pleasure’ and ‘good’ could refer to the same thing and yet it still be an open question to ask “is pleasure good?”

Moore’s Intuitionism

Having argued against ethical naturalism, Moore sets out his own version of ethical non-naturalism, which he calls intuitionism.

We might ask Moore: if moral properties are non-natural properties, how do we know about them?

It’s no mystery how we know about natural properties, such as blueness, roundness, or largeness. But non-natural properties are more difficult to explain – they’re not like ordinary physical properties that can be scientifically investigated.

Moore’s response to this problem is intuition. He argues that, via the faculty of rational intuition, we can directly reflect on the truth of moral judgements such as “murder is wrong”. The truth/falsehood of such moral judgements is said to be self evident.

Problems for ethical non-naturalism:

Anti-realist theories

Anti-realist metaethical theories argue that mind independent moral properties do not exist. So, there are no such things as true moral facts.

The syllabus looks at 3 anti-realist metaethical theories:

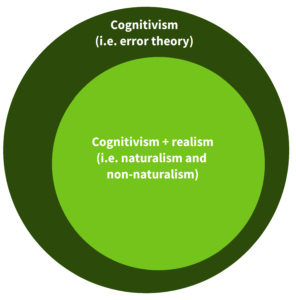

- Error theory says moral judgements are cognitive statements but properties don’t exist

- Emotivism says moral judgements are non-cognitive statements that express feelings of approval or disapproval

- Prescriptivism says moral judgements are non-cognitive statements that are intended as instructions

Error theory

Error theory says that moral judgements are beliefs that are intended to be true or false (cognitivism). However, error theory also says that moral properties don’t exist (anti-realism) and so these moral judgements are all false.

So, according to error theory, the statement “murder is wrong” expresses a cognitive belief that murder is wrong – but ‘wrong’ refers to a non-existent property and so the statement is false. It’s like if someone believed a colour called ‘blellow’ existed and said “grass is blellow” – this statement would be false because ‘blellow’ doesn’t exist.

Since moral properties don’t exist according to error theory, it claims that all moral propositions – e.g. “murder is wrong” – are false. So, not only is “murder is wrong” false but “murder is good” is also false because ‘goodness’ doesn’t exist either.

Arguments for cognitivism

Mackie’s book starts with various arguments in favour of cognitivism generally.

Moral philosophy, he argues, has tended to assume objective moral values (e.g. Plato and Kant) – i.e. that moral judgements are objectively true or false.

Not only that, ordinary language assumes cognitivism as well. To illustrate this, Mackie uses the example of someone facing the moral dilemma of whether to engage in research related to bacteriological warfare. In trying to resolve this dilemma, you don’t ask how you feel about it – you ask whether such action is wrong in itself.

Having established that moral judgements are cognitive and thus aim to be true or false, Mackie next turns his attention to the nature of moral properties. Mackie argues that such moral properties do not exist (i.e. he argues for moral anti-realism).

The argument from relativity

Mackie’s first argument for anti-realism starts by pointing out that there are variations in moral beliefs between cultures (and between the same culture at different time periods).

For example: Some cultures are polygamous, other cultures think this is wrong. Some cultures think eating certain animals is wrong, other cultures eat those animals. And historically, many cultures have kept slaves, but most modern cultures think this is wrong.

If moral realism is correct, there would only be one objectively correct answer to all of these issues. Why, then, is there so much disagreement on these issues? Cultures that are independent of each other tend to form completely different moral practices and beliefs. We can explain this disagreement in one of two ways:

- One culture has, for some reason, discovered objective moral reality while the other hasn’t

- Each culture has different conditions and a different way of life and has developed their own moral beliefs in response to that

Mackie’s argument is that the second option is the more plausible account. If moral realism were true, you wouldn’t expect to see such divergent moral beliefs.

To put it another way, if there were objective moral properties and facts (i.e. if moral realism were true), you would expect every culture to eventually discover these moral facts in a similar way to how every culture has discovered other objective truths such as “1+1=2”.

The argument from queerness

Mackie’s main argument for moral anti-realism is that moral properties would have to be very strange (or ‘queer’, to use Mackie’s term). His reasons:

- Epistemically queer: If mind-independent moral properties exist, then it is a total mystery how we would acquire knowledge of them. Whereas natural knowledge can be explained naturally, moral knowledge can’t be explained in the same way and instead requires spooky hypotheses such as Moore’s intuitionism

- Metaphysically queer: If mind-independent moral properties exist, they must be metaphysically unlike anything else we have experience of. For example, ‘good’ things would need to somehow have to-be-doneness built into them and ‘bad’ things would have not-to-be-doneness built into them. Like, the act of stealing itself would have to have the property of ‘don’t do this!’ built into it, which doesn’t make sense. It’s not possible for objective, physical, objects to relate to human motivations in this way (scientifically, metaphysically, or otherwise).

Note: Mackie’s arguments here are primarily directed at the idea of non-natural moral properties.

Another way of getting at the metaphysical weirdness is to question how moral facts relate to natural facts. Imagine someone stealing from a shop. Then imagine someone stealing from a shop and that this action has the property of wrongness. What’s the difference between the two cases? What does the property of ‘wrongness’ add to the natural facts of the situation? It’s not clear.

Mackie argues that the queerness of moral properties – both epistemic and metaphysical – is evidence that moral properties do not exist.

Problems for error theory

Non-cognitivism

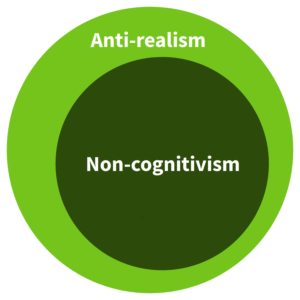

Non-cognitivists believe that moral judgements such as “murder is wrong” express non-cognitive mental states. Non-cognitive statements do not aim to describe reality and so are not supposed to be taken as either true or false. Non-cognitivists do not believe in the existence of moral properties that would make moral statements true or false and so all non-cognitivist metaethical theories are also anti-realist theories.

The syllabus lists two non-cognitivist metaethical theories: Emotivism and prescriptivism.

Emotivism

Emotivism says that moral judgements express (non-cognitive) feelings of approval or disapproval.

So, according to emotivism, when someone says “murder is wrong!”, what they really mean is “boo! murder!”

(By the way, “boo!” here is like when people “boo!” at a football match, not “boo!” like when you jump out at someone to scare them. This doesn’t really come across in text…)

Similarly, when someone says “giving money to charity is good”, what they are really expressing is “hooray! Giving money to charity!”

Notice how none of these attitudes are capable of being true or false. They are just expressions of approval or disapproval – not beliefs. Hence, emotivism is a non-cognitivist theory.

Hume: Treatise of Human Nature

Before getting on to Hume’s argument for emotivism specifically, Hume provides two arguments for the view that moral judgements are not judgements of reason – i.e. that moral judgements are non-cognitive.

(you can use these arguments to argue against any of the cognitivist theories: naturalism, non naturalism and error theory)

Moral judgements motivate action

According to Hume, judgements of reason – e.g. a belief that grass is green – don’t motivate us to act in any way. Instead, it’s emotions and desires that motivate us to act. For example, my desire to drink beer might motivate me to seek out beer.

According to Hume, moral judgements seem more like the beer-drinking example because they motivate action. For example, my belief that “murder is wrong” will motivate me not to murder or my belief that “giving money to charity is good” will motivate me to give money to charity.

So, Hume’s argument here is essentially:

- Moral judgements can motivate action

- Judgements of reason cannot motivate action

- Therefore, moral judgements are not judgements of reason

- (In other words, moral judgements are non-cognitive)

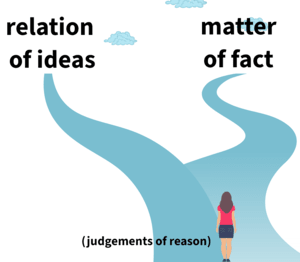

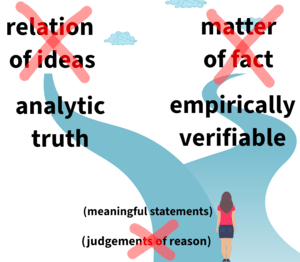

Hume’s fork (again)

If you remember Hume’s fork from epistemology, Hume argued there are just two types of judgements of reason (i.e. cognitive judgements): relations of ideas and matters of fact.

If you remember Hume’s fork from epistemology, Hume argued there are just two types of judgements of reason (i.e. cognitive judgements): relations of ideas and matters of fact.

Applying Hume’s fork to moral judgements, he argues:

- Moral judgements are not relations of ideas (because we can conceive of “murder is wrong” as being either true or false)

- Moral judgements are not matters of fact either (because we can’t observe or empirically verify that “murder is wrong”)

- Therefore, moral judgements are not judgements of reason (i.e. moral judgements are non-cognitive)

The is/ought problem

Hume argues that moral ought statements are a completely different kind of thing to factual is statements.

| ‘Is’ statements | ‘Ought’ statements |

| Factual claims about what is the case | Value judgements about what should be the case |

| E.g. “That is an act of torture” or “Smith murdered Jones” | E.g. “You ought not torture people” or “Smith shouldn’t have murdered Jones” |

Hume argues that there is a gap between the two kinds of claim: You cannot logically derive ought statements like ‘you ought not torture’ from statements about what is, such as ‘that is an act of torture’. We can argue that this is evidence for non-cognitivism: the reason we cannot derive ‘ought’ statements from ‘is’ statements is because the former type of statement is non-cognitive while the latter is cognitive.

Hume would say ‘is’ statements like “Smith murdered Jones” are capable of being true or false, whereas ‘ought’ statements like “Smith shouldn’t have done that” are expressions of emotion that are not capable of being true or false:

Morality, therefore, is more properly felt than judg’d of

A.J. Ayer: Language, Truth and Logic

The verification principle

(The verification principle also comes up in religious language)

The verification principle: a statement only has meaning if it is either:

- An analytic truth (e.g. “a triangle has 3 sides”)

- Empirically verifiable (e.g. “water boils at 100c”)

Any statement that does not fit these descriptions is meaningless, according to the verification principle.

Ayer argues that moral judgements fail the verification principle. Firstly, “murder is wrong” is clearly not an analytic truth. Ayer also argues that “murder is wrong” is not empirically verifiable either – both on the naturalist and non-naturalist interpretations:

- Naturalism would argue that we could prove that murder causes pain, anger, etc. However, Ayer argues that this is not the same as proving murder is wrong. Hence, Ayer rejects naturalism: We can empirically verify that murder causes pain, say, but we cannot empirically verify that murder is wrong.

- Ayer also argues that there is no way to empirically verify the presence of non-natural properties. Even if “murder is wrong” did possess the non-natural property of wrongness, how could we ever prove this? It’s not empirically verifiable, nor is it an analytic truth. Hence, Ayer also argues against non-naturalism: The existence of non-natural properties cannot be empirically proven.

So, moral judgements are not analytic truths, nor are they empirically verifiable. Therefore, according to the verification principle, they are meaningless.

Instead of expressing factual statements about the external world, Ayer concludes that moral judgements simply express feelings of approval or disapproval and seek to evoke the same feelings in others:

“If I say to someone, “you acted wrongly in stealing that money” […] I am simply evincing my moral disapproval of it. It is as if I had said, “You stole that money,” in a peculiar tone of horror.”

So, like Hume, Ayer is an emotivist.

Prescriptivism

Prescriptivism says that moral judgements express (non-cognitive) instructions that aim to guide behaviour.

So, according to prescriptivism, when someone says “murder is wrong!”, what they really mean is something like “don’t murder people!”

When you instruct someone to do something – e.g. “shut the door” – you are not expressing a belief that is capable of being true or false. Hence, emotivism is a non-cognitivist theory.

R.M. Hare: The Language of Morals

Hare agrees with emotivism that moral judgements express (non-cognitive) attitudes. But Hare argues this isn’t main point of moral judgements: The main point of moral judgements is to guide conduct. For example, “stealing is wrong” implies the imperative “don’t steal”.

As well as the above analysis of moral judgements, Hare provides an analysis of general value terms such as ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘right’, and ‘wrong’. Hare argues that the meaning of these terms is not simply to describe but mainly to commend or criticise.

Hare uses an example of a ‘good’ strawberry to illustrate how value judgements work: A purely descriptive analysis of ‘good strawberry’ might reduce its meaning to ‘sweet and juicy strawberry’. But description is clearly not the only thing I mean when I say “this is a good strawberry” because there are ways in which we use language that conflict with this analysis. For example, I might say “this is a good strawberry because it is sweet and juicy” – and this statement doesn’t make sense on the purely descriptive analysis because it would be like saying “this is a sweet and juicy strawberry because it is sweet and juicy”. So, according to Hare, ‘good strawberry’ does not simply describe, it also commends the strawberry.

But in order to commend (or criticise) something, we must assume a certain set of standards. In the example above, the standards against which I commended the strawberry were ‘sweet and juicy’. However, these standards are not objective and there are no facts that can determine one set of standards as correct or incorrect.

Returning back to moral value judgements, these work in a similar way to the strawberry: When I say “she is a good person” I am assuming a certain set of moral standards and commending that person against those standards. This commendation is the primary meaning of ‘good’ and provides (imperative) guidance on how others should act.

Problems for non-cognitivism

Moral argument and reasoning

(note: the following argument applies to non-cognitivist theories (i.e. prescriptivism and emotivism) but not cognitivist theories (e.g. error theory))

Non-cognitivism appears to be at odds with how we typically use moral judgements because we often use moral judgements as part of moral reasoning. For example:

- If murder is wrong, then paying to have someone murdered is wrong

- Murder is wrong

- Therefore, paying to have someone murdered is wrong

This seems like a valid argument – the conclusion seems to follow logically from the premises.

But if non-cognitivism is correct, it’s hard to see how this is a valid argument at all. It seems the meaning of “murder is wrong” changes between the first and second premises:

- In premise 2, “murder is wrong” is by itself and so, according to non-cognitivism, it means some non-cognitive statement (e.g. “boo! Murder!” or “don’t murder!”)

- But in premise 1, “murder is wrong” is presented differently. It’s presented as something that, if true, implies something else. However, according to non-cognitivism, “murder is wrong” cannot be true or false because it is a non-cognitive statement

The problem for non-cognitivism is that people regularly embed moral judgements in statements like in premise 1 above – they say things like “if murder is wrong then” and “if stealing is bad then”.

But if non-cognitivism is correct, it’s hard to make sense of why people do this. Why would people embed moral judgements in sentences like this or make arguments involving moral judgements if moral judgements were incapable of being true or false?

Mackie’s arguments for cognitivism

See error theory section above.

Problems for anti-realism

(note: the following problems apply to all anti-realist theories (i.e. error theory, prescriptivism and emotivism))

Moral nihilism

If moral anti-realism is true, it can be argued that this leads to moral nihilism: the view that no actions are inherently wrong. There’s nothing true about moral judgements such as “murder is wrong”. This then raises the question of why anyone should bother to be moral at all.

Possible response:

Non-cognitivists can respond that just because there’s no inherent right or wrong, people still have moral attitudes and feelings. And the realisation that moral values are just expressions of feelings doesn’t mean we should (or could) stop having these moral feelings.

It’s also somewhat self-defeating to be a moral nihilist according to non-cognitivism. After all, living as if there are no moral values is itself an expression of a certain attitude or feeling.

Cognitivist anti-realist theories (i.e. error theory) have a harder time responding to the charge of moral nihilism. One response could be to just accept the charge of moral nihilism and argue that, though undesirable, this doesn’t make error theory any less true.

There may also be practical reasons to behave as if some moral judgements are true. For example, if you were always stealing from your friends, chances are they wouldn’t remain friends with you for very long.

Moral progress

Our moral values have changed over time. For example, it was considered morally acceptable to keep slaves back in the time of Plato but it’s not today.

If we accept that such changes are examples of moral progress, then we can make an argument along these lines:

- If moral anti-realism is true, then there would be no moral progress

- But there has been moral progress

- Therefore moral anti-realism is false

Possible response:

This is a somewhat question-begging argument though. The second premise essentially assumes the conclusion. Why should the anti-realist accept there’s been objective moral progress when he doesn’t accept the existence of objective morality in the first place?

However, we can define moral progress in less question-begging ways. For example, we could argue that our morality has become more consistent over time, or that we have adapted our moral values in response to greater knowledge of the facts.