Overview – The Limits of Knowledge

The limits of knowledge is about philosophical scepticism and whether it is possible to know anything at all.

This topic brings together several arguments that come up elsewhere in the epistemology module – the main one being Descartes’ 3 waves of doubt. Descartes’ third wave of doubt – the evil demon argument – is an example of global/philosophical scepticism because it casts doubt on pretty much everything we ordinarily consider to be knowledge.

The point of considering extreme sceptical scenarios like the evil demon is to determine what, if anything, we can know. The responses to scepticism listed on the syllabus are:

Scepticism

Philosophical scepticism vs. normal incredulity

In our everyday lives, we doubt things all the time. For example, you might be unsure whether a friend’s birthday is the 17th or the 18th of August, or what time the philosophy exam is, or you might doubt your memory of a fact such as ‘Paris is the capital of France’. This is ‘normal incredulity’ or ‘ordinary doubt’ in the language of the philosophy syllabus.

Philosophical doubt goes beyond such ordinary doubt and casts uncertainty over pretty much everything we think we know. There are a bunch of global sceptical scenarios in philosophy and popular culture, such as:

- Descartes’ evil demon

- The Matrix

- The simulation hypothesis

- Perfect virtual reality

- Brain in a vat

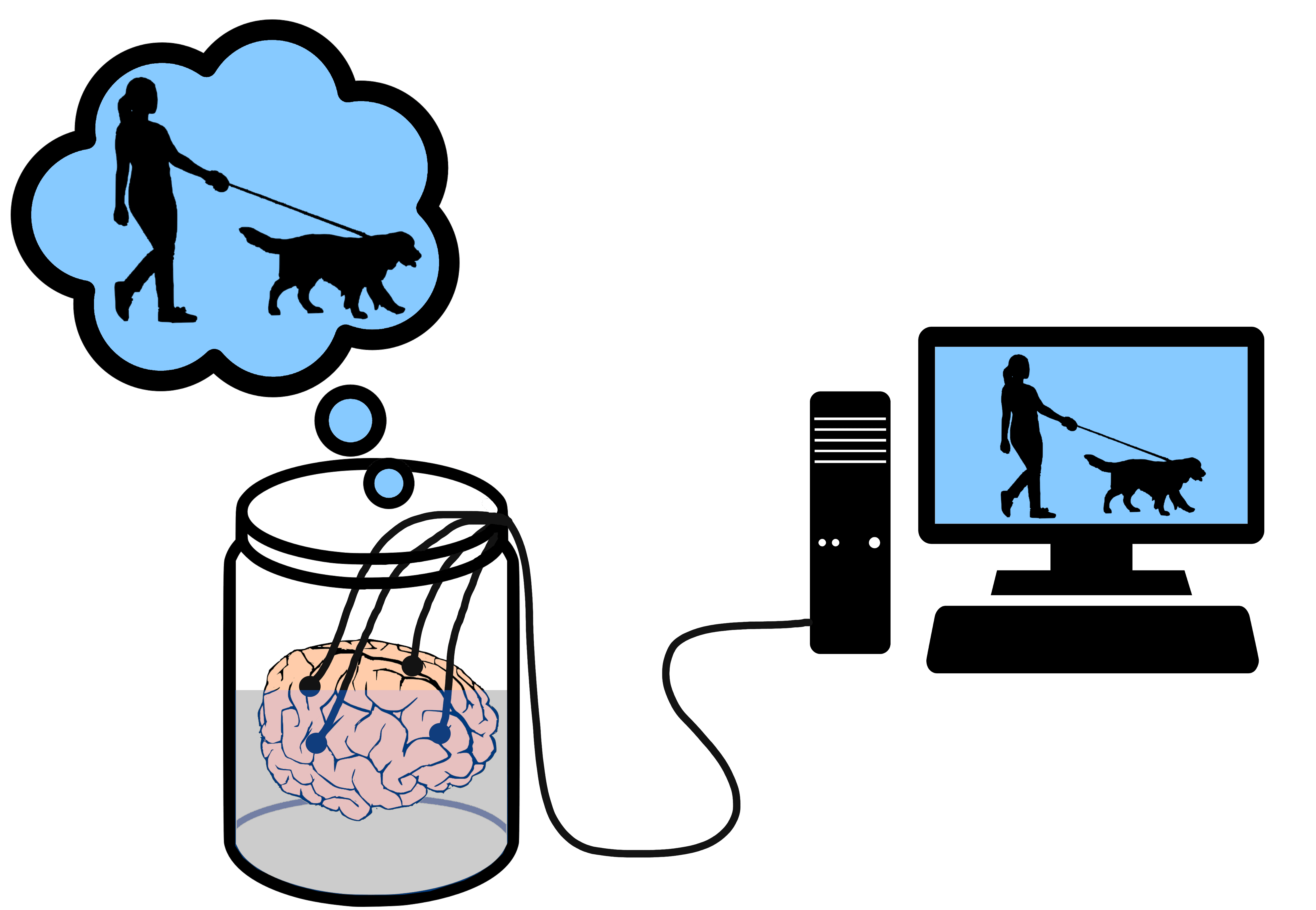

This last one – brain in a vat – comes up quite often in philosophy. The scenario is this: If all your experience is just electrical signals interpreted by your brain, then you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference if you were a disembodied brain in a vat being fed these same electrical signals artificially.

So, in the brain in a vat scenario, you might think “I’m outside walking my dog” but in reality you are just a disembodied brain in a vat being fed electrical signals that make it feel like you are outside walking your dog. So, if you are a brain in a vat, your belief “I’m outside walking my dog” would be false and there would be no way of knowing.

All the global sceptical scenarios above play the same role here: They are situations where everything you believe could be false and there would be no way of knowing.

Descartes’ evil demon

We’ve already covered Descartes’ 3 waves of doubt in knowledge from reason. The third wave of doubt – the evil demon argument – is another example of global or philosophical scepticism.

“I shall suppose, therefore, that there is, not a true God, who is the sovereign source of truth, but some evil demon, no less cunning and deceiving than powerful, who has used all his artifice to deceive me. I will suppose that the heavens, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds, and all external things that we see, are only illusions and deceptions which he uses to take me in.”

– Descartes, Meditation 1

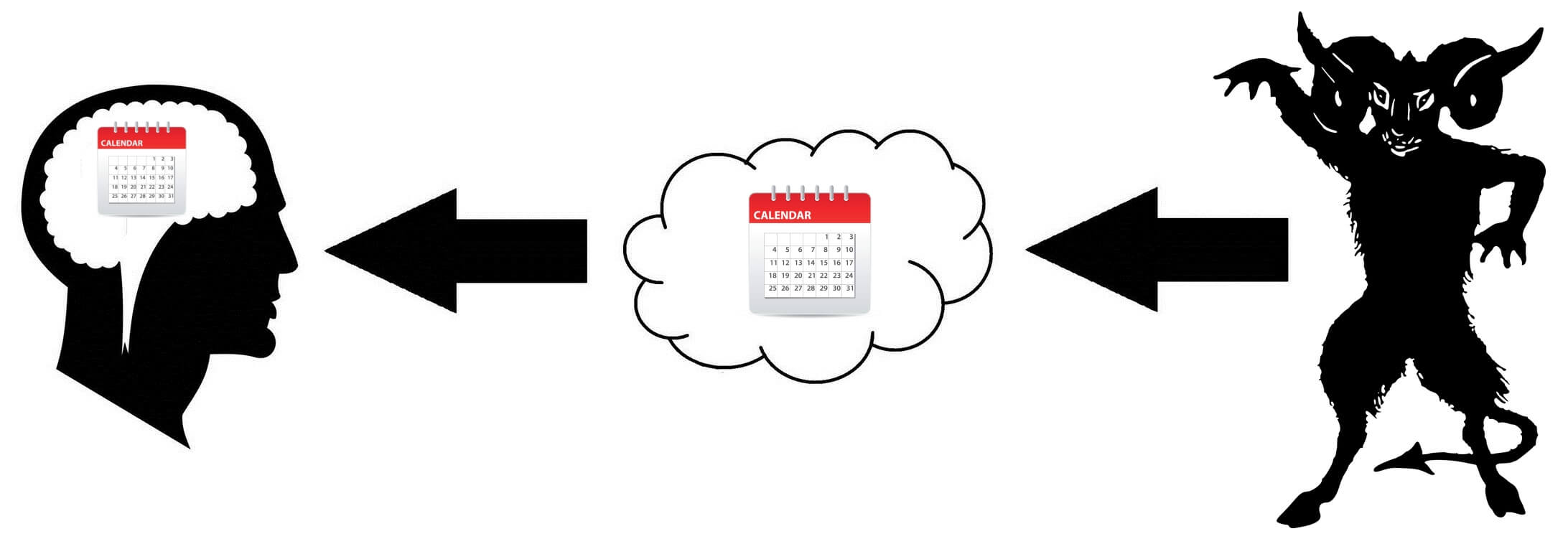

In cases of ordinary doubt, you can often resolve them by referring to some sort of justification. If I doubt which day my friend’s birthday is, for example, I can check my calendar to make sure. Once I see their name under the 17th, I can be confident my belief that “my friend’s birthday is on the 17th” is true.

But global scepticism scenarios like Descartes’ evil demon go beyond such normal incredulity and cast doubt on all our typical methods of justification. If all my experience is just an illusion created by an evil demon, then I can’t trust my calendar – I can’t even trust my visual perception. For all I know, my friend doesn’t even exist and my perceptions of him were just an illusion created by the evil demon. If I can’t even be sure my friend exists, then I definitely can’t be sure what day his birthday is.

You can run the same sort of argument for pretty much any ordinary knowledge proposition:

- “I know that grass is green”

- Nope, the evil demon was tricking you and grass is actually purple

- “I know that Paris is the capital of France”

- Nope, the evil demon was tricking you – the world you think you know was just an illusion created by the evil demon. France doesn’t even exist, let alone Paris

- “I know that 2 + 2 = 4”

- Nope, the evil demon is messing with you again. 2 + 2 actually equals 5 and each time you add the two numbers together, the evil demon messes with your mind and makes you think the answer is 4

All of these scenarios are possible – and there is no way you would be able to tell otherwise. Thus, the possibility of the evil demon undermines all our usual justifications and casts doubt over everything we ordinarily consider to be knowledge. We could be constantly making mistakes and there would be no way of telling otherwise.

The global sceptic thus believes that all knowledge is impossible.

Responses

Descartes’ own response

We cover Descartes’ own responses to scepticism in more detail in the knowledge from reason section, but in short:

- Descartes’ cogito argument shows that, even if he is being deceived by the evil demon, he can at least be certain of the proposition “I exist”.

- Descartes then goes on to argue that he can also know that God exists

- Having established that God exists, and that God would not allow him to be globally deceived, Descartes concludes that he can trust his perceptions and so he can trust that the external world exists.

If Descartes can justify trust in his perceptions, then his perceptions justify his knowledge of ordinary propositions. For example, Descartes can know “I have hands” because he can see his hands and he knows that God wouldn’t allow him to be deceived about something like that. Thus, Descartes has defeated global scepticism and defended ordinary knowledge.

Possible response:

There are all sorts of ways the sceptic could reject Descartes’ chain of justification here. For example, Descartes’ justification of his perceptions relies on his arguments for God’s existence, such as the trademark argument. However, if we can show that these arguments fail, then the chain of justification is broken and the sceptical problem re-emerges: Perhaps an evil demon is causing his perceptions.

Russell’s response

In the indirect realism topic, we saw Russell’s response to the sceptical challenge that says the existence of the external world is the best hypothesis. Adjusting that argument slightly for the evil demon scenario, we could say the following:

- Either:

- A: the external world exists and causes my perceptions

- B: an evil demon exists and causes my perceptions

- I can’t prove A or B definitively

- So, I have to treat A and B as hypotheses

- A is a better explanation of my experience than B

- So, mind independent objects exist and cause my perceptions

Possible response:

We can respond, however, that the fact we can’t prove A or B definitively was Descartes’ whole point! Descartes wasn’t trying to prove the evil demon does exist, he was saying that it was possible – i.e. that it was a viable hypothesis – and so we can’t trust our ordinary knowledge.

However, Russell could respond back that the possibility of the evil demon hypothesis does not mean knowledge is impossible. Just because we can’t know for certain that we’re not being deceived by an evil demon, that does not mean we can’t have knowledge. Descartes is assuming an infallibilist definition of knowledge here – he’s assuming that we have to know we’re not being deceived by an evil demon in order to have knowledge. Russell could respond that certainty is not necessary: Sure, we might be being deceived by an evil demon and we can’t know either way, but as long as we’re not being deceived and our beliefs are true then our ordinary (uncertain) justifications are sufficient for knowledge.

Another way the sceptic could respond to Russell’s argument is to dispute that the external world is the best hypothesis at all. If we are being deceived by an evil demon, or are in the matrix, or are brains in vats, then our experience would appear exactly the same to us as if it was caused by the external world. Thus, we have no grounds to prefer one hypothesis over the other: The available evidence supports both hypotheses equally.

Locke’s response

We also saw in the indirect realism section that Locke provides two responses to the sceptical challenge. These were:

- Perception, unlike imagination, is involuntary – this suggests perception is caused by something external to my mind

- My different perceptions – e.g. sight and sound – are coherent, suggesting there is a common reality that causes both

Possible response:

The sceptic can respond, though, that even though Locke succeeds in proving something external is causing his perceptions, he doesn’t succeed in proving that this perception is in any way an accurate representation of the external world. The external something that is causing his (involuntary) perceptions could be an evil demon that is deceiving him.

The sceptical response to Locke’s point about the coherence of different senses is similar: Just because our different senses are coherent, it doesn’t do much to prove they are representative of reality. An evil demon could create coherent experiences – e.g. he could deceive you into hearing dogs barking at the same time as seeing dogs – and there is no way you could tell otherwise. The evil could just be creating coherent sound and visual perceptions.

Berkeley’s response

Berkeley’s idealism rejects mind-independent objects right off the bat and so sceptical scenarios where mind-independent objects don’t exist or are radically different from our perceptions aren’t really possible. The evil demon argument never really gets going against idealism because idealism doesn’t make a distinction between perceptions and reality: “To be is to be perceived” as Berkeley says.

Berkeley argues that his perceptions must be caused by something outside of him and, given the complexity of these perceptions, Berkeley concludes that this cause must be the mind of God. Berkeley’s theory of perception here is almost like a benevolent version of the evil demon: God is causing his perceptions but, rather than being a deception, those perceptions just are what reality is.

Possible response:

For this response to succeed, idealism must be the correct theory of perception. But idealism faces various problems, such as illusions and hallucinations.

Reliabilism

The reliabilism definition of knowledge says that knowledge is true belief formed via a reliable method. Assuming I’m not being actually deceived by an evil demon, then my perception would count as a reliable method of gaining knowledge because my perceptions reliably cause me to form true beliefs.

Of course, I can’t prove either way whether I’m being deceived by an evil demon – but that doesn’t matter. I don’t have to know my perception is reliable in order for it to count as a reliable method – it just is. Consider the following two scenarios:

- Scenario 1: I am not a brain in a vat

- My perception is a reliable method because I’m living in the real world and am perceiving it accurately

- My perception leads me to the belief “I have hands”

- My belief is true, because this is scenario 1 and I’m not a brain in a vat

- So I have a true belief formed via a reliable method that “I have hands”

- So, according to reliabilism, I know “I have hands” in scenario 1

- (so, if you’re not actually a brain in a vat, you can know “I have hands”)

- Scenario 2: I am a brain in a vat

- My perception is not a reliable method because I’m a brain in a vat being fed artificial stimuli

- My perception leads me to the belief “I have hands”

- But my belief is false, because this is scenario 2 and I’m actually a brain in a vat

- So I have a false belief formed via an unreliable method that “I have hands”

- So, according to reliabilism, I do not know “I have hands” in scenario 2

- (which would be correct – you don’t want a definition of knowledge that says you know you have hands when you don’t have hands)

The point is: If we’re in scenario 1, then we can have knowledge of ordinary propositions such as “I have hands”.

Yes, we can’t know whether we’re in scenario 1 or 2, and so we can’t know that we know such propositions – but we don’t have to. You can know something without knowing that you know that thing.

Assuming we’re not in some weird sceptical scenario like the evil demon or brain in a vat, then knowledge is possible if ‘knowledge’ is defined as true belief formed via a reliable method. If I am not a brain in a vat, then my perception is as a reliable method and so I can know ordinary propositions such as “I have hands”.

Possible response:

However, the sceptic can respond that reliabilism is not the correct definition of knowledge (e.g. because of fake barn county). If we go with some other definition of knowledge – such as infallibilism or justified true belief – then we can’t provide proper justification for ordinary knowledge because we can’t justify that we’re not in some sceptical scenario. So, if any of the other definitions of knowledge are correct, I cannot know “I have hands” without first defeating the sceptical challenge and we’re back to square 1.