Overview – The Concept of God

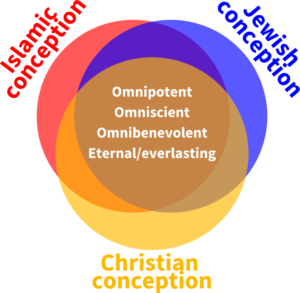

The concept of God in A level philosophy is the concept of God as understood by the 3 main monotheistic religions: Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.

Typically, these religions agree that God has the following 4 divine attributes:

Typically, these religions agree that God has the following 4 divine attributes:

However, there are a number of arguments which claim that these characteristics are incoherent or logically inconsistent.

A level philosophy looks at 3 problems with this concept of God. These are:

The divine attributes

God, as commonly understood, has a number of key characteristics. These characteristics can be described as the ‘divine attributes’. The divine attributes are as follows:

Omnipotence

Omnipotence literally translates as all powerful.

God is imagined to be perfectly powerful – it’s not possible for there to exist a being with more power than God.

But this doesn’t mean God can do literally anything. For example, God can’t make “triangles have 4 sides” true, because it is a logical contradiction.

Omnipotence is thus best understood as the claim that God can do anything that’s logically possible.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) argued that this isn’t a real limitation on God’s power. For something to be logically impossible is for it to contain a contradiction.

However, it is argued that the concept of omnipotence is itself contradictory. For more information, see the problem of the stone.

Omniscience

Omniscience literally translates as all knowing.

This is to say God has perfect knowledge. He knows everything – or, at least, everything it is possible to know.

For example, it is argued that God doesn’t know what we humans are going to do in the future – because we have free will. The claim is still that God knows everything it’s possible to know – but that it is not possible to know the future. For more information, see free will vs. omniscience.

Omnibenevolence

Omnibenevolence literally translates as all loving.

It’s best understood as the claim that God is perfectly good. God always does what’s morally good – He never does anything bad or evil.

Eternal/everlasting

There is disagreement among religious philosophers as to whether God is eternal or everlasting:

- Everlasting: God exists within time

- Eternal: God exists outside of time

If God exists within time, then He is everlasting. This is to say He was there at the beginning of time and will continue to exist forever.

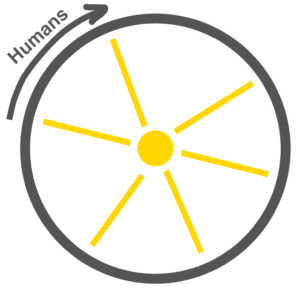

The concept of an eternal God is more difficult to imagine. If God exists outside of time, then He has no beginning or end as these concepts only make sense within time. The 6th century theologian Boethius described God’s eternal relationship with time as:

“that which embraces and possesses simultaneously the whole fullness of everlasting life, which lacks nothing of the future and has lost nothing of the past, that is what may properly be said to be eternal.”

So, whereas humans experience time in succession, i.e. one moment at a time, an eternal being experiences all moments simultaneously. In other words, what we call the ‘past’ and ‘future’ are just as present to God as what we call the ‘present’ is to us.

Building on Boethius’ description, philosophers Eleonore Stump and Norman Kretzmann distinguish between 2 types of simultaneity:

- T-simultaneity: This applies to temporal (within time) beings, like humans. Humans can perceive two things happen simultaneously in the present moment only.

- E-simultaneity: This applies to atemporal (outside of time) beings, like God. God can perceive multiple things happening simultaneously at all times (what we would call the past, present, and future) from the perspective of an eternal present. For example, from God’s perspective, He can perceive you on your 7th birthday whilst simultaneously perceiving you on your 17th birthday.

Problems/inconsistencies

The problem of the stone

If God is omnipotent (all powerful), can God create a stone so heavy He can’t lift it?

If God is omnipotent (all powerful), can God create a stone so heavy He can’t lift it?

- If He can’t then he’s not powerful enough to create this stone

- But if He can then he’s not powerful enough to lift the stone

Either way, there is something God cannot do – which means He’s not omnipotent.

Possible response:

George Mavrodes replies to the problem of the stone by arguing that ‘a stone an omnipotent being can’t lift’ is not a possible thing – it’s a contradiction. And, as discussed in omnipotence, it’s not necessarily a limitation on God’s power to say He can’t do what’s logically impossible.

The euthyphro dilemma

The Euthyphro dilemma takes its name from Plato‘s Euthyphro.

Back then, it was directed against the many Gods of ancient Greece. However, it can be adapted to the modern concept of God.

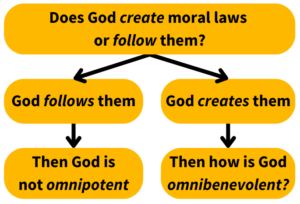

The Euthyphro dilemma looks at whether morality is created by, or independent of, God.

Applied to the moral judgement ‘torturing babies is wrong’, we can ask:

- Is torturing babies wrong because God says it’s wrong?

- Or, does God say ‘don’t torture babies’ because it is wrong?

If the second option is the case – in other words morality is independent of God – then it’s a challenge to God’s omnipotence. The reason for this is that God’s power would be limited by morality. God is not powerful enough to make ‘torturing babies is good’ true, for example.

But if the first option is true – and so God created morality – then God could say ‘torturing babies is good’, or whatever He wanted, and it would be true. Why, then, does God say some things are bad and not others? What reason is there for choosing the rule ‘torturing babies is wrong’ over the rule ‘torturing babies is good’? The answer, surely, is nothing and so good and bad are arbitrary. But if goodness is arbitrary, it’s hard to make sense of the claim ‘God is good’ or why anyone would praise God for being good. This presents a challenge to God’s omnibenevolence.

It seems that whichever option we choose – God creates morality or God follows morality – means rejecting a key concept of God (either omnipotence or omnibenevolence).

Possible response:

We could argue that God chooses the rules of morality based on His other attributes, such as love. For example, God could have chosen to make ‘torturing babies is good’ true. However, God loves humanity and doesn’t like to see us suffer and so for this reason God chose to make ‘torturing babies is bad’ true instead. This would mean goodness and badness are not arbitrary whims but are instead grounded in some justification (God’s love).

Omniscience vs. free will

- As an omniscient being, God knows everything.

- If God knows everything, then He must know what I’m going to do before I do it – for example, drink tea

- If God already knows that I’m going to drink the tea before I do it, then it must be true that I drink the tea

- If it’s true that I drink the tea, then it can’t be false that I drink the tea.

- In other words, I don’t have a choice. And if I don’t have a choice to either drink or not drink the tea, then I don’t have free will.

So, either:

- God is omniscient but we don’t have free will

- We have free will but God is not omniscient

A possible reply is that God’s omniscience should be understood as the claim that God knows everything it is possible to know. The whole point of free will is that it makes it impossible to know the future (that’s what ‘free will’ means). So, God is is still omniscient in the sense He knows everything that is possible to know.

Alternatively, we could respond that as an eternal being God exists outside of time and so is observing (and thus knows) our freely chosen actions of the future. This is how Boethius (see above) resolved the free will vs. omniscience dilemma:

“And if human and divine present may be compared, just as you see certain things in this your present time, so God sees all things in His eternal present… No necessity forces the man to walk who is making his way of his own free will, although it is necessary that he walks when he takes a step. ‘In the same way… God sees those future events which happen of free will as present events; so that these things when considered with reference to God’s sight of them do happen necessarily as a result of the condition of divine knowledge; but when considered in themselves they do not lose the absolute freedom of their nature. All things, therefore, whose future occurrence is known to God do without doubt happen, but some of them are the result of free will.”

– Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy