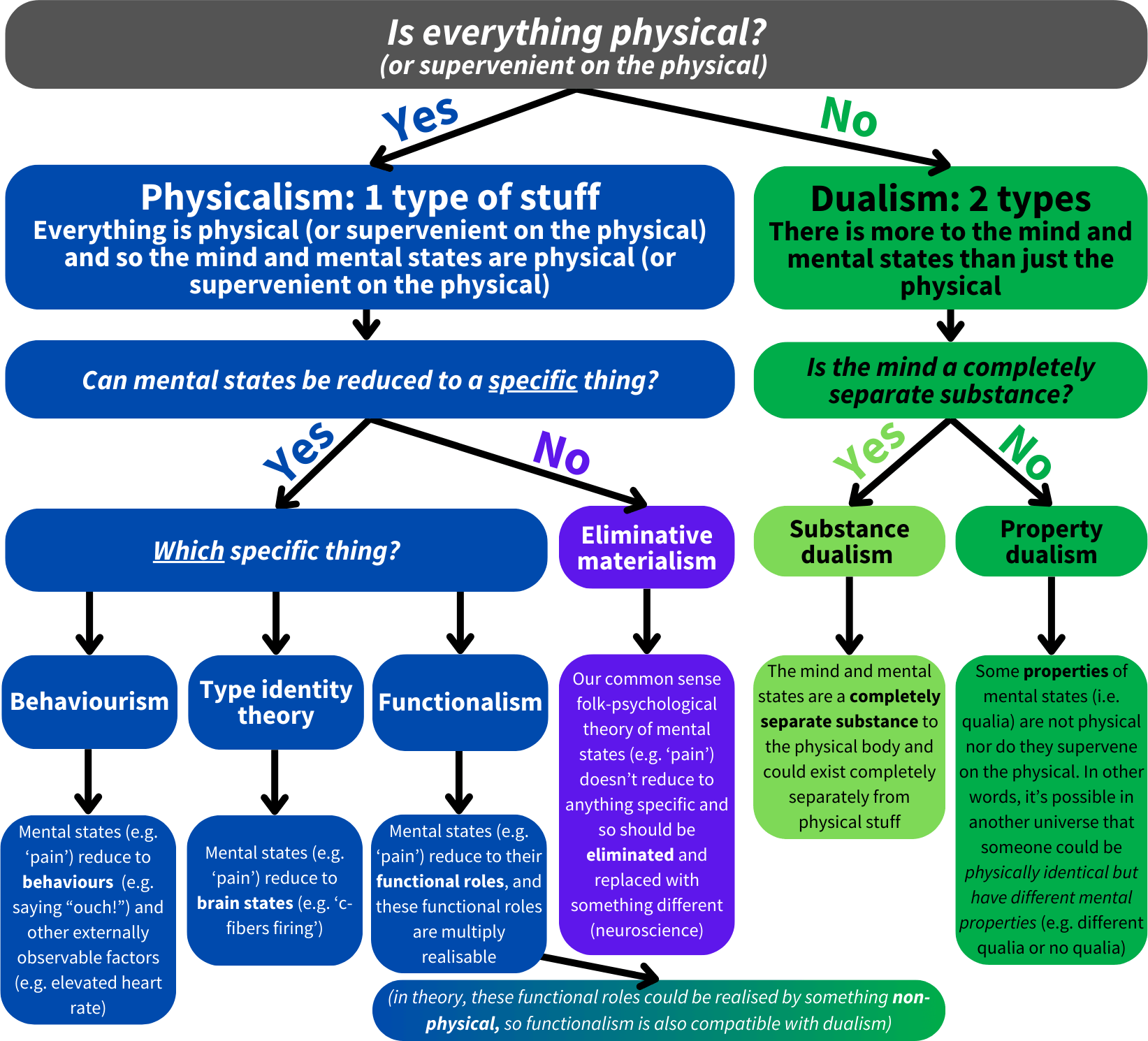

Overview – Dualism

Dualist theories of the mind argue that there are two kinds of thing – hence, dualism.

The opposing view to dualism is physicalism: the view that everything is completely physical (or supervenes on the physical).

The syllabus looks at two forms of dualism:

| Substance dualism |

Property dualism |

|

| Summary | The mental and the physical are two completely different kinds of substance | Some mental properties (qualia) are non-physical and do not supervene on the physical |

| Arguments for | ||

| Arguments against |

Substance dualism

“Minds exist and are not identical to bodies or parts of bodies.”

Substance dualism says there are two completely different kinds of substance in our universe:

- Mental substances

- Physical substances

Physical substances are things like the trees, cars, houses, etc. Your body – your arms, legs, etc. – is a physical thing as well.

The brain is part of the body, hence it is also physical. But dualists deny that the mind is the same thing as the brain. Instead, dualists argue that the mind is something completely different to the brain – something non-physical. Dualism says that minds can exist completely independently of physical stuff.

Most people who believe in souls are dualists. Typically, the soul isn’t thought of as a physical thing – you can’t touch it, or see it, for example. Similarly, things like ghosts and angels are somewhat dualist – they’re not thought to be made of physical stuff.

Descartes’ conceivability argument

René Descartes‘ conceivability argument for substance dualism can be summarised as:

- I have a clear and distinct idea of my mind as a thinking thing that is not extended in space

- I have a clear and distinct idea of my body as a non-thinking thing that is extended in space

- Anything I can conceive of clearly and distinctly is something that God could create

- So, God could create my mind as a thinking thing that is not extended in space and my body as a non-thinking thing that is extended in space

- So, it is possible for mind and body to exist independent of each other

- So, mind and body are two separate substances

In other words, Descartes is saying that it is conceivable – and therefore possible – for mind and body to exist separately. He then takes this to show that mind and body are separate things.

Note: It may seem a bit of a leap from it’s possible that mind and body are separate to mind and body are separate. But this topic is about what the mind is – its identity. If it’s possible for the mind to exist without the body, then what the mind is cannot be the same thing as the body (or any part of the body).

Responses

Mind without body is inconceivable

Behaviourism would argue that mind without body is not even conceivable:

- Behaviourism says that to have mental states is to have behavioural dispositions

- To have behavioural dispositions is to be disposed to move your body in certain ways

- It is inconceivable to be disposed to move your body in certain ways if you don’t have a body

- So, it is inconceivable to have mental states if you don’t have a body

- So, mind without body is inconceivable

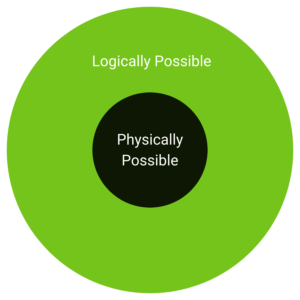

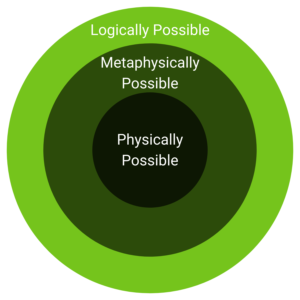

What is conceivable may not be (physically) possible

Just because we can imagine the mind floating around independently of a body, this doesn’t mean it is physically possible. It might be logically possible – i.e. it doesn’t involve a logical contradiction – but just because something is logically possible, this doesn’t mean it is physically possible!

For example: it is not logically possible for a triangle to have 4 sides because it involves a logical contradiction.

But it is logically possible for me to jump on to the moon from earth. It might be physically impossible, but there is no logical contradiction in this idea!

Similarly, just because it’s conceivable/logically possible for a mind to exist independently of a body, this doesn’t automatically mean such a thing is physically possible.

Masked man fallacy

Another response to the conceivability argument attacks Descartes’ inference from the claim that mind without body is conceivable to the conclusion that mind exists without body in reality. The fallibility of this inference can be shown with the following example:

- I conceive of Batman as a caped crusader

- I conceive of Bruce Wayne as a billionaire who is not a caped crusader

- Therefore, Batman is not Bruce Wayne

If you know the Batman story, Batman is Bruce Wayne’s secret identity. So the conclusion is clearly false: Batman is Bruce Wayne.

So, even though it may be conceivable that Batman is someone else, this tells us nothing about how things are in reality. To think otherwise is to fall for the masked man fallacy.

The reason this argument is fallacious is because it switches from talking about ideas to talking about things themselves. But, like the Batman example, sometimes our ideas are mistaken and reality is different from our idea of it. We can argue that Descartes’ conceivability argument makes the same mistake as the Batman example:

- Just because you have an idea of Batman and Bruce Wayne as separate people, this doesn’t mean they are separate people

- Similarly, just because you have an idea that the mind and body are separate things, this doesn’t necessarily mean they are separate things

Descartes’ divisibility argument

Descartes’ divisibility argument can be summarised as:

- My body is divisible

- My mind is not divisible

- Therefore, my mind and body are separate things

(This argument makes use of Leibniz’s law of identicals, which says that for A and B to be the same thing, A and B must have all the same properties. If two things have different properties, they cannot be the same thing).

The first premise is definitely true. If you chopped you leg or your arm off, you would be dividing up your body.

The mind, however, does not seem divisible – at least not in the same way. You can’t, for example, have half a thought.

Responses

The mind is divisible

There are cases of mental illness in which the mind does seem literally divided. For example, someone with multiple personality disorder could be said to have a divided mind.

Another example of this would be people who have literally had their brain cut in half. A corpus callosotomy is a surgical procedure for epilepsy where the main connection between the left and right hemispheres of the brain is severed. Perhaps surprisingly, patients go on to live perfectly normal lives – although there can be a few weird side effects:

“I said, ‘do you believe in God?’, and the right hemisphere went straight to yes. I asked the same question to the left hemisphere […] it went to no right away.”

This suggests that dividing the brain can, in fact, divide the mind.

So, the second premise of Descartes’ argument appears to be false: the mind is divisible.

Not everything that is physical is divisible

We can also respond by arguing that even if the mind is indivisible, this doesn’t necessarily prove Descartes’ conclusion that the mind is a separate kind of substance. Instead, it’s possible that the mind is just an indivisible type of physical substance.

Obviously, you can divide the physical body: The examples above of cutting off a leg or an arm show this. But if you keep dividing it, you might eventually reach a point where you cannot divide it any further. Eventually, for example, you’ll just be left with a load of atoms, and perhaps those atoms could be divided into sub-atomic particles, but eventually you might reach a form of physical substance that is indivisible (units of energy, say, or whatever physics says – the specifics don’t really matter). The point is this:

- If it’s possible to reach a point where physical matter becomes indivisible, then not everything that is indivisible is non-physical

- And so, even if Descartes successfully shows that the mind is indivisible, this doesn’t prove that the mind is non-physical

- It’s possible that the mind is the same kind of substance as the body (i.e. a physical substance) – it’s just an indivisible form of that same substance.

Problems for Substance dualism

The problem of other minds

Each of us only ever experiences our own thoughts, sensations, feelings, etc. We might empathise when we see someone hurt themselves but we don’t literally feel their pain. If we both look at the same sunset we are looking at the same thing but each of us is having a different, private, experience in our mind.

Yet even though you might never literally experience my thoughts, you’d still assume I have them (except maybe in weird philosophical contexts like this one). You don’t seriously doubt whether your friends, family, and random people on the street have minds. You infer from their behaviour that they have a mind that causes their behaviour.

But if substance dualism is true, what grounds do you have to make this assumption? Minds and bodies are two completely separate and independent substances. How do you know there is a mind ‘attached’ to a body? It’s completely possible, on the dualist view, to have physical behaviour without a physical mind. In such a case, what evidence could you possibly find which proves other minds exist at all? It seems substance dualism leads to scepticism about the existence of other people’s minds.

Possible response #1: Mill’s argument from analogy

John Stuart Mill responds to the problem of other minds by drawing an analogy between his own mind and the minds of others:

- I have a mind

- My mind causes my behaviour

- Other people have bodies and behave similarly to me in similar situations

- By analogy, their behaviour has the same type of cause as my behaviour: a mind

- Therefore, other people have minds

However, the problem of other minds can respond that one example of a relationship between mind and behaviour (my own) is not sufficient to prove the relationship holds in all cases. It would be like saying “that dog has 3 legs, therefore all dogs have 3 legs.”

It’s a dubious inference to go from one instance of a relationship (I have a mind that causes my behaviour) to the claim that this relationship holds in all instances (everyone has a mind that causes their behaviour).

Possible response #2: Other minds are the best explanation

Another response to the problem of other minds accepts that we can’t observe or prove the existence of minds, but says we should believe in their existence anyway since they are the best explanation (i.e. an abductive argument).

One way you could argue other minds are the best explanation is their explanatory and predictive power: If other people have minds, it explains why they behave in the ways they do. For example, if someone spends a few minutes before moving a chess piece in a chess match, the best explanation of their behaviour is that they have a mind and were using it to think through their move before making it.

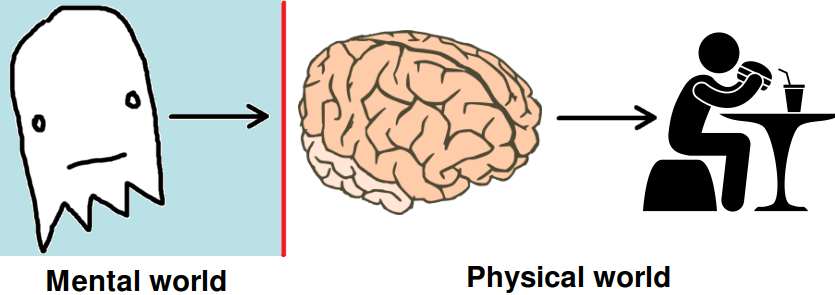

Causal interaction

Another issue for substance dualism is how mental things can causally interact with physical things when they are supposed to be two completely separate substances.

Our mental states affect how we behave. If I’m feeling hungry (mental state), it might cause me to move my body (physical thing) to the fridge to get some food.

But if the mental state is non-physical, how does it transfer over into the physical world and cause things to happen?

Note: this is mainly an issue for interactionist dualism, not so much for epiphenomenal dualism.

The conceptual interaction problem

It’s easy to explain how physical things interact with one another. When you kick a football, the atoms of your leg (physical thing) connect with the atoms of the ball (also a physical thing) and the ball moves. There’s no mystery here.

But it’s hard to see how a non-physical thing would interact with a physical thing in the same way. It would be like punching a ghost: your hand would go straight through!

This objection was put to Descartes himself by his student, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, and is known as the conceptual interaction problem:

- Physical things only move if they are pushed

- Only something that is physical and can touch the thing that is moved can exert such a force

- But the mind is not physical, so it can’t touch the body

- Therefore, the mind cannot move the body

We know (4) is false, so there must be a problem elsewhere in the argument.

Of all the premises, (3) seems easiest to dispute. It follows from this that the mind is, in fact, physical. And if the mind is physical then substance dualism is wrong.

The empirical interaction problem

The syllabus also mentions a more scientific/empirical approach to the causal interaction problem, known as the empirical interaction problem:

- The law of conservation of energy says that: In a closed system, energy cannot be added or removed – it can only be transferred

- Our universe is such a closed system

- If substance dualism is true, it would mean energy is constantly being added into the closed system of our universe every time the mental interacts with the physical

- So, if substance dualism is true, the law of conservation of energy is false

- But there is a lot of evidence (e.g. Noether’s theorem) to suggest that the law of conservation of energy is true

- So, substance dualism must be wrong

Conservation of energy is a big deal in physics and chemistry, so if it’s a choice between substance dualism and the law of conservation of energy, most scientists would go with the latter option, rejecting substance dualism.

Property dualism

“There are at least some mental properties that are neither reducible to nor supervenient upon physical properties.”

Property dualism is the view that there is that some minds have non-physical properties.

It doesn’t go as far as substance dualism in claiming that the mind is completely non-physical, but it differs from physicalism in that property dualists believe a complete description of the physical universe would not be a complete description of the entire universe. Instead, property dualists believe that a complete physical description of the universe would miss out qualia.

Some definitions

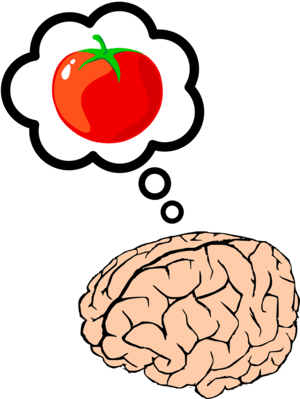

Qualia

“Qualia are intrinsic (and non-intentional) phenomenal properties that are introspectively accessible.”

In plain English, qualia are the subjective properties of experience – i.e. what something feels like inside. Examples of qualia include:

In plain English, qualia are the subjective properties of experience – i.e. what something feels like inside. Examples of qualia include:

- The redness I experience when I look at a ripe tomato

- The taste of beer when I have a drink

- The rough feeling when I run my hand over some sandpaper

Notice how qualia are not properties of the objects – i.e. properties of the tomato, or the beer, or the sandpaper – they are properties of experience of those objects.

Knowledge of qualia is sometimes called phenomenal knowledge – i.e. knowledge of what it is like to have a certain experience.

@philosophymania What is qualia? https://philosophyalevel.com/aqa-philosophy-revision-notes/dualism/#QualiaD #philosophy #philosophytiktok #alevelphilosophy #mind #spooky ♬ original sound – philosophymania

Supervenience

“X supervenes on Y if a change in Y is necessary for a change in X”

Supervenience is a relationship between two kinds of thing. If something supervenes on something else, then it is dependent on that thing.

In metaphysics of mind, physicalism says that everything – including the mind and mental states – is either physical or supervenes on the physical. In other words, physicalism says that two physically identical things must be the same in every way: it’s impossible for two physically identical things to be mentally different.

Property dualism denies this claim, however. According to property dualism, it’s possible for two physically identical things to be different in some way. More specifically, property dualism says it’s possible that two physically identical things could have different mental properties – different qualia.

So, according to property dualism, qualia are neither physical nor supervene on the physical.

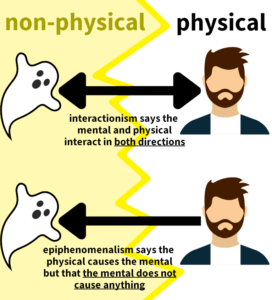

Interactionism and epiphenomenalism

It’s worth introducing another distinction here, between epiphenomenalist and interactionist dualism:

It’s worth introducing another distinction here, between epiphenomenalist and interactionist dualism:

- Interactionist dualism: the mind can interact with the physical world and the physical world can interact with the mind. In other words, the mental and physical can interact in both directions.

- Mental -> physical: The mental state of hunger causes you to go and get food

- Physical -> mental: Getting hit in the head causes the mental state of pain

- Epiphenomenalist dualism: the physical world can cause mental states but mental states cannot cause changes in the physical world – i.e. the causal interaction is one way.

- Physical -> mental: Getting hit in the head causes the mental state of pain

- But mental states (i.e. qualia) themselves don’t cause anything: My going to get food is explained by my (physical) brain state, rather than my mental state

Some (most) property dualists are epiphenomenalists – they believe that qualia are caused by physical things but that qualia doesn’t cause anything itself. Epiphenomenalism thus avoids some of the causal interaction issues facing substance dualism because it does not have to explain how the mental can cause changes in the physical.

For the purposes of A level philosophy, you can think of epiphenomenalism as basically the same thing as property dualism, and interactionism as basically the same thing as substance dualism.

David Chalmers: The zombie argument

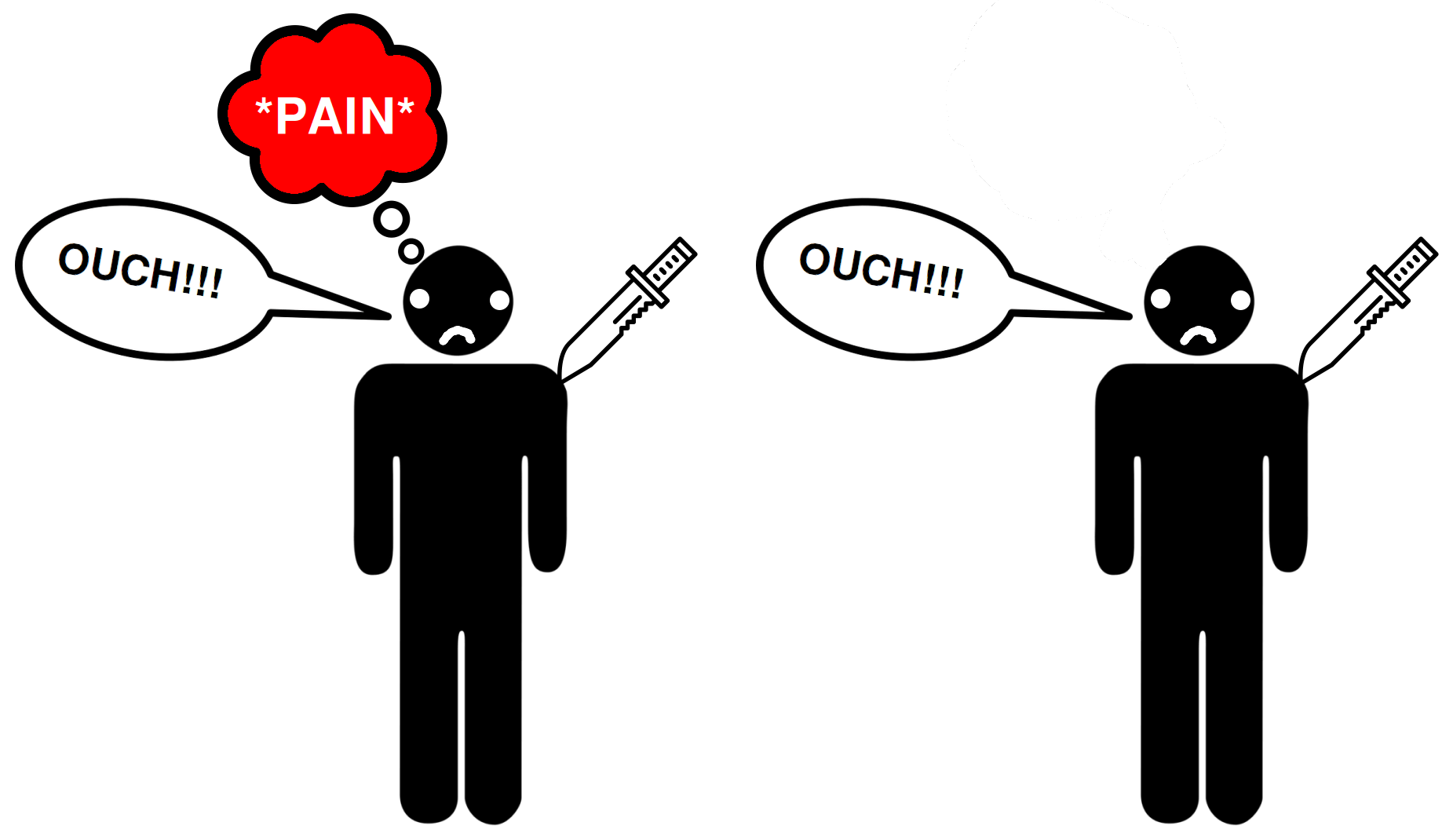

A philosophical zombie is a person who is physically and functionally identical to an ordinary human – except they don’t have any qualia.

A zombie will say “ouch!” when it gets stabbed and its physical brain will even fire in the same way as a normal brain – but there isn’t any pain qualia internally.

Such zombies seem conceivable. We can imagine a possible world that is physically identical to this one, with the same people, but without qualia. In this world, you would behave and act in exactly the same way as in the actual world except you’d have no phenomenal experience.

We can use this intuition to form an argument for property dualism similar to Descartes’ conceivability argument:

- Philosophical zombies are conceivable

- If philosophical zombies are conceivable then philosophical zombies are metaphysically possible

- If philosophical zombies are metaphysically possible then qualia are non-physical

- If qualia are non-physical then property dualism is true

- Therefore, property dualism is true

Responses to the zombie argument

Zombies are not conceivable

Physicalists can respond that if we had enough physical knowledge we would be able to understand what we currently call ‘qualia’ in purely physical terms. In other words, the only reason zombies seem conceivable is because we are confused or missing some important information. The conceivability of a physical duplicate without qualia is just an illusion – albeit a very powerful one.

The reason zombies seem conceivable is because we’re labouring under a false illusion that qualia are these spooky non-physical things. Once we understand that qualia are, in fact, just physical things, then it becomes inconceivable to imagine a physically identical being that lacks these physical features. Imagining a philosophical zombie would be like saying “imagine something that is physically identical but that isn’t physically identical” – it would be a contradiction, and contradictions aren’t conceivable. It would be like trying to imagine a married bachelor or a triangle with 4 sides.

Once we understand that qualia = a physical thing, it becomes inconceivable for two physically identical beings not to have identical qualia, and so the zombie argument fails to prove property dualism.

Zombies are not (metaphysically) possible

We’ve already seen how logical possibility does not guarantee physical possibility. But we can introduce a third kind of possibility – metaphysical possibility – and respond to the zombie argument by arguing that conceivability does not guarantee metaphysical possibility.

It seems conceivable, for example, that water could be something other than H2O because a statement like “water is H3O” is not obviously contradictory in the same way “a triangle has 4-sides” is contradictory.

“Water is H2O” is not an analytic truth and so it seems that we can imagine water without imagining something with the chemical structure H2O. In contrast, we cannot imagine a triangle without imagining a 3-sided shape because “triangles have 3 sides” is an analytic truth. The apparent conceivability of “water is H3O” suggests such a thing is somehow possible.

However, some philosophers would reject that “water is H3O” is possible because H2O is an essential property of what water is. Sure, you can imagine a possible world where the clear liquid in lakes and rivers is H3O, but then what you’d be imagining wouldn’t be water! It would be something else. “Water is H3O” is thus metaphysically impossible.

Similarly, if phenomenal properties (qualia) are essential properties of some physical things, then it’s not metaphysically possible for the same physical thing to have different phenomenal properties. In other words, a physical duplicate without qualia (i.e. a philosophical zombie) is metaphysically impossible in the same way water without H2O is metaphysically impossible.

Frank Jackson: the knowledge argument (Mary)

Mary is confined to a black-and-white room, is educated through black-and-white books and lectures relayed on a black-and-white television. In this way she learns everything there is to know about the physical nature of the world. She knows all the physical facts about us and our environment, in a wide sense of ‘physical’ which includes everything in completed physics, chemistry, and neurophysiology, and all there is to know about the causal and relational facts consequent upon all this, including of course functional roles. If physicalism is true, she knows all there is to know.

– Frank Jackson, What Mary Didn’t Know

So, in this thought experiment, Mary has learned all the physical facts about our world from within a black and white room. She knows every possible physical fact – including every physical fact about human experience of colour.

Physicalism argues that everything is physical and so there are only physical facts and knowledge of physical things.

However, Jackson uses this thought experiment to show that Mary doesn’t have all knowledge despite having all physical knowledge. It follows from this that there is such thing as non-physical knowledge. Jackson continues:

It seems, however, that Mary does not know all there is to know. For when she is let out of the black-and-white room or given a color television, she will learn what it is like to see something red, say. […] Hence, physicalism is false.

So, in short, the argument looks something like this:

- Mary knows all the physical facts about colour

- Mary does not know what it feels like to see colour

- Therefore, what it feels like to see colour is not a physical fact

- Physicalism says that all facts are physical facts

- Therefore, physicalism is false

Physicalism is taken to be false due to the supposed existence of non-physical facts. These non-physical facts are facts about non-physical properties, i.e. qualia. If such non-physical properties exist, then property dualism is true.

Responses to the knowledge argument

Ability hypothesis

Remember from epistemology the three kinds of knowledge:

- Ability: knowledge how – e.g. “I know how to ride a bike”

- Acquaintance: knowledge of – e.g. “I know Fred well”

- Propositional: knowledge that – e.g. “I know that London is the capital of England”

We can accept that Mary learns something new when she leaves the black and white room but reject Jackson’s claim that this new knowledge is non-physical.

Instead, we might argue, Mary gains new ability knowledge.

There is nothing spooky or non-physical about knowing how to ride a bike. The fact that people are able to ride bicycles is not used as an argument against physicalism.

And we can imagine a similar case to the Mary example. However, this time, Mary learns all the physical facts about riding a bicycle (and all the related causal and relational facts) from books and videos, etc. without ever actually touching a bike for herself.

When Mary is given a bicycle for the first time she probably won’t be able to ride it – even though she knows all the physical facts about riding bicycles. This is because knowledge of how to ride a bike isn’t the kind of knowledge you can learn from facts in books. It’s ability knowledge. And ability knowledge is a kind of physical knowledge.

Applied to the original Mary case, some argue when Mary sees red for the first time all she does is gain new abilities. She gains the ability to imagine red, for example. She also gains the ability to distinguish red sensory experiences from green sensory experiences.

Acquaintance hypothesis

Similar to the argument above, we can claim that although Mary learns something new, her new knowledge is still a kind of physical knowledge: knowledge by acquaintance.

Chances are you don’t know King Charles III personally – even if you know a load of facts about him. Even if you learned every physical fact about King Charles III you still couldn’t say you know him if you’d never met him.

But King Charles III’s acquaintances and friends do know him personally. But there’s nothing spooky or non-physical about their knowledge.

You can make a (sort of) similar argument for Mary’s experience of seeing the colour red.

She can know all the physical facts about red – what it is, when people see it, how they react to it, etc. – without being acquainted with redness itself.

Mary is not acquainted with redness because her own brain has never had this property itself. But when she sees red for the first time the property occurs in her brain and she becomes acquainted with redness. Mary gains new knowledge from being acquainted with redness in this way.

New knowledge, old fact

There is more than one way to know the same fact.

For example, “I know there is water in that glass” expresses knowledge of the same underlying physical fact that “I know there is H2O in that glass” does.

But it’s possible to know the former and not know the latter. For example, back before the chemical structure of water was discovered, it’s possible that someone could know “there is water in the glass” but not know “there is H2O in the glass”.

The same fact can be understood via two different concepts.

You could argue it’s a similar case with Mary’s knowledge of what it’s like to see red.

Before she left the black and white room, Mary only knew about redness in theoretical terms. But when she leaves and sees red she gains a new concept: the phenomenal concept. And it’s impossible to know what it’s like to see red without this concept.

We can argue that this phenomenal concept just provides a different way of understanding the same underlying fact.

So, Mary doesn’t learn any new, non-physical fact. She just learns a different way of understanding the same fact.

Mary would already know

Another objection would be to reject a main premise of Jackson’s argument: that Mary would learn something new. It’s a similar argument to the qualia don’t exist response to the zombie argument.

We could argue that, if Mary really did know all the physical facts about what it’s like to see red (as the thought experiment claims), then this would include knowledge of what it’s like to see red.

In other words, Mary would already know what it’s like to see red before she left the black and white room.

This claim goes against an intuition most people have. We can’t imagine how Mary could know what it’s like to see red without having seen it herself.

But how can we know that all physical knowledge about seeing red wouldn’t also include knowledge of what it’s like to see red? How can we even imagine what it would be like to have all physical knowledge about something like this?

The intuition that Mary wouldn’t know what it’s like to see red is just that – an intuition. What solid argument is there that all physical knowledge would not also include knowledge of what it’s like to see red?

Problems for property dualism

Note: these are mainly issues for epiphenomenal dualism, because they target the epiphenomenalist claim that qualia have no causal powers.

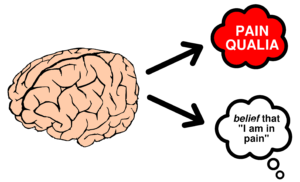

Introspective self-knowledge

The (epiphenomenal) property dualist’s claim that qualia and mental states do not themselves have causal powers raises an issue: How do we know about our own mental states?

Epiphenomenalism usually explains away the apparent causal effects of qualia by saying that it’s the brain that causes both qualia and behaviour. For example, when I burn my hand on a hot stove, my brain state causes me to pull my hand away and also causes the unpleasant qualia/mental state. Here, the qualia/mental state is just an effect of the brain state – it doesn’t actually cause anything itself.

But this explanation raises a problem in the case of self-knowledge: If qualia/mental states have no causal powers, then knowledge of qualia/mental states is impossible. If my brain state is all that causes my beliefs about my mental state, then I would have the same beliefs about my mental state even if the qualia was completely different.

When I have the brain state of pain, for example, my pain qualia could be like my red qualia, or swap places with my pleasure qualia, or disappear entirely, and I would still form the same belief “I am in pain”. This means that, at best, we could only ever have knowledge of our brain states, never knowledge of our mental states/qualia.

So, if property dualism is true, it seems to imply that introspective self-knowledge (of mental states) is impossible – but this seems obviously wrong. You can make the argument in this way:

- If epiphenomenalism is true, qualia have no causal effects

- If qualia have no causal effects, then knowledge of mental states is impossible

- But knowledge of mental states is possible (e.g. I can know “I am in pain”)

- So, epiphenomenalism must be false

The phenomenology of mental life

In addition to causing knowledge of our mental states (see above), qualia also seem to cause other mental states.

For example, if someone is in constant chronic pain, this may cause them to feel sad. It seems plausible that the unpleasant feeling of being in pain (i.e. the qualia) caused the mental state of sadness – this explanation is perfectly reasonable.

But, if epiphenomenalism is correct, qualia have no causal powers. So this explanation can’t be correct – it wouldn’t be possible for pain qualia to cause sadness (or any other mental state). But this conclusion seems false: It seems obvious that qualia do cause other mental states, and so epiphenomenalism must be false.

Evolution

Evolution says that genetic mutations occur randomly. Over millions of years, the environment selects for genes that give some benefit – either in terms of survival or reproduction. For example, having long neck genes enables a giraffe to reach food and survive. Or, to put it another way, having a long neck causes the giraffe not to die of starvation. The causal effects of long neck genes clearly explain why giraffes have long necks: They are beneficial for survival in the physical world.

But, if epiphenomenalism is true, there would be no evolutionary benefit to having qualia because epiphenomenal qualia doesn’t have any causal effect.

It makes sense why animals would evolve brain states – for example, the brain state of pain would cause the animal to get away from things that might damage its body or kill it. But, if epiphenomenalism is true, the brain state alone would cause the animal to move away from whatever is damaging its body – the brain state alone would cause it to behave in exactly the same way whether it had qualia or not. So, there would be no evolutionary benefit of having epiphenomenal qualia in addition to the brain state.

And so, if minds are the product of evolution, it would suggest that epiphenomenalism is false: Qualia does have some useful causal role, otherwise we wouldn’t have evolved it.