Overview – Knowledge from Reason

This A Level philosophy topic examines whether all our knowledge comes from perception or whether there are other – a priori – sources of knowledge. There are really two separate debates in this topic, and these are:

Broadly speaking, empiricism says that all knowledge comes from experience. But innatism and intuition and deduction are two ways rationalism can reject empiricism:

- Rationalism’s intuition and deduction thesis says that we can acquire some knowledge purely through intuition and deduction (i.e. we can acquire knowledge purely by thinking rather than through perceptual experience).

- Rationalism’s innate knowledge thesis says that we are born with some knowledge already (and innate knowledge obviously doesn’t come from perceptual experience because you haven’t had any perceptual experience when you are newly born).

Some definitions

A lot of the discussion (in particular rationalism vs. empiricism) draws on the following terms.

Analytic / synthetic

Analytic and synthetic are two different kinds of truths.

| Analytic truth | Synthetic truth |

| True in virtue of the meaning of the words | True in virtue of how the world is |

| E.g. “A bachelor is an unmarried man” or “triangles have three sides” | E.g. “Grass is green” or “water boils at 100°c” |

Analytic truths cannot be denied without resulting in a logical contradiction. To say, “not all bachelors are unmarried”, for example, is to misunderstand the word bachelor – the concept of a married bachelor does not make sense. Similarly, one cannot coherently imagine a triangle with four sides because the very idea involves a contradiction.

Denial of a synthetic truth does not lead to a logical contradiction. For example, we can coherently imagine red grass in denial of the synthetic truth “grass is green”. Though experience tells us grass is not, in fact, red, there is no logical contradiction in this idea.

A priori / a posteriori

A priori and a posteriori are two different kinds of knowledge:

| A priori knowledge | A posteriori knowledge |

| Knowledge that can be acquired without experience of the external world, through thought alone | Knowledge that can only be acquired from experience of the external world |

| E.g. working out what 900 divided by 7 is | E.g. doing an experiment to discover the temperature at which water boils |

Intuition and deduction

Intuition and deduction are a priori methods for gaining knowledge:

- (Rational) intuition: The ability to know something is true just by thinking about it

- E.g. Descartes’ cogito argument below

- Deduction: A method of deriving true propositions from other true propositions (using reason)

- E.g. You can use deduction to deduce statement 3 from statements 1 and 2 below:

- If A is true then B is true

- A is true

- Therefore, B is true

- E.g. You can use deduction to deduce statement 3 from statements 1 and 2 below:

In the overview above, we defined rationalism as the view that we can acquire some knowledge purely through intuition and deduction. This is slightly inaccurate, though, because even an empiricist would admit there is some knowledge that can be known purely through intuition and deduction. For example, you clearly don’t need empirical experience to work out that “2×75=150” because it is an analytic truth. So actually, what empiricists say is that you can’t acquire knowledge of synthetic truths using intuition and deduction:

- Empiricism says all a priori knowledge is of analytic truths (i.e. there is no synthetic a priori knowledge)

- Rationalism says not all a priori knowledge is of analytic truths (i.e. there is at least one synthetic truth that can be known a priori using intuition and deduction)

Most of the time, empiricism holds true. If you take any synthetic truth, such as “water boils at 100°c”, it seems impossible that we could learn it without some a posteriori experience of the world (e.g. an experiment).

So, most synthetic truths are known a posteriori. But the question is whether this relationship holds true all the time or just some of the time. Rationalism says the latter: There is at least one synthetic truth that can be known a priori through intuition and deduction.

Descartes: Meditations

René Descartes‘ Meditations provides arguments for 3 synthetic truths using a priori intuition and deduction. The synthetic truths Descartes argues for are:

If Descartes’ arguments for these claims work and are purely a priori, then they support the rationalist claim that some synthetic truths can be known a priori.

The three waves of doubt

Before seeking to establish what he can know, Descartes first seeks to doubt everything he thinks he knows. If it’s possible to doubt it, then he does.

These sceptical arguments have come to be known as the three waves of doubt. They are:

- Illusion

- Dreaming

- Deception

First off, Illusion. I can doubt the reliability of my sense experience as it has deceived me in the past. For example, a pencil in water may look crooked even though it isn’t.

Second, I might think I’m awake when I’m actually dreaming. I might believe I’m looking at a computer screen, but if I’m simply dreaming that I am, then my belief is mistaken.

But even if I’m dreaming, there are still basic ideas that are common to both dreams and reality. For example, that “1+1=2” – can this be doubted?

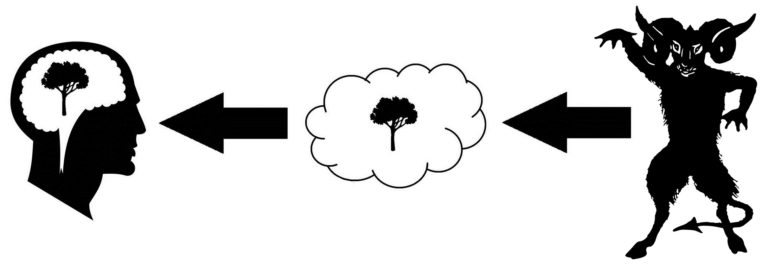

Yes, says Descartes, if I am being deceived. An evil demon may be controlling my entire experience, making me think I’m correctly adding 1 and 1 when I’m not.

So, basically anything I think I know can be doubted – an evil demon may be controlling my perception and making me have nothing but false beliefs. The evil demon scenario could be true, and there is no way I would be able to tell the difference. So, the possibility of the evil demon scenario casts doubt on everything I know.

This position of extreme doubt is known as global scepticism.

Cogito ergo sum

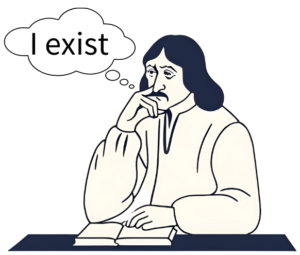

So, Descartes is currently in a position of extreme scepticism. Is there anything he can know for certain?

Yes:

Yes:

dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum

This translates as:

- I doubt

- Therefore I think

- Therefore I am

The shortened version – cogito ergo sum – is probably the most famous phrase in philosophy. Descartes’ point is that even if the evil demon is trying to deceive him on just about everything, Descartes cannot doubt that he exists.

The reason for this is that even if the demon is deceiving him, there must be something for the demon to deceive in the first place! The fact that Descartes is able to doubt his own existence is proof that he does, indeed, exist, and so:

“I am, I exist, is necessarily true, every time I express it or conceive of it in my mind.”

– Descartes, Meditation 2

Clear and distinct ideas

“I call that clear which is present and manifest to the mind giving attention to it… but the distinct is that which is so precise and different from all other objects as to comprehend in itself only what is clear.”

– Descartes, Principles of Philosophy, XLV

- Clear: Clear ideas are those that a focused mind can recognise without any confusion or ambiguity. For example, the idea of a triangle as a three-sided shape is clearly defined.

- Distinct: Ideas that are not only clear but also sharply separated from all other ideas, with no ambiguity or overlap. For example, the idea of ‘triangle’ (3-sided) is distinct from ‘square’ (4-sided).

Upon reflection of the cogito ergo sum argument, Descartes claims that his certainty in the proposition ‘I exist’ is due to the fact that it is a clear and distinct idea. Having a clear and distinct idea is not simply a feeling of certainty, though – it is a recognition that it’s impossible for the proposition to be false. So, Descartes knows ‘I exist’ is true simply by thinking about it.

This property – where the truth of an idea presents itself clearly and distinctly – goes back to the idea of rational intuition. Rational intuition is an a priori faculty that enables us to see truth. According to Descartes, any idea that presents itself as clear and distinct to our rational intuition can be trusted as true:

“And consequently it seems to me that I can already establish as a general rule that all the things we conceive very clearly and distinctly are true.”

– Descartes, Meditation 3

Arguments for the existence of God

Descartes builds on these clear and distinct ideas via deduction. He gives several arguments for the existence of God using intuition and deduction:

- Descartes’ ontological argument

- Descartes’ cosmological argument

- The trademark argument

Descartes’ ontological and cosmological arguments are covered in the metaphysics of God module, so we’ll just cover his trademark argument here:

“Now it is manifest by the natural light that there must be at least as much reality in the efficient and total cause as in its effect… And hence it follows… that the more perfect… cannot be a consequence and dependence of the less perfect… By the name of God I understand an infinite substance… And consequently I must necessarily conclude… that God exists; for, although the idea of substance is in me… I would not, nevertheless, have the idea of an infinite substance… since I am a finite being, unless the idea had been put into me by some substance which was truly infinite.”

– Descartes, Meditation 3

This argument can be summarised as:

- I have the concept of God

- My concept of God is the concept of something infinite and perfect

- But I am a finite and imperfect being (finite reality)

- The cause of an effect must have at least as much reality as the effect

- So, the cause of my concept of God must have as much reality as what the concept is about

- So, the cause of my idea of God must have as much reality as an infinite and perfect being (i.e. must have infinite reality)

- So, God exists

This argument is called the ‘trademark’ argument because Descartes argues that concept of God (premise 1) is like an innate ‘trademark’ placed in our minds.

Premise 4 is sometimes referred to as the causal adequacy principle. An example that perhaps illustrates this is getting punched by a ghost: This wouldn’t leave a physical bruise because the effect (physical reality) would have more reality than the cause (non-physical reality).

Because of this causal adequacy principle, Descartes argues that it’s impossible this trademark – of an infinite and perfect being – is something he could have created himself, because Descartes only has finite reality but this idea is of something with infinite reality. Whatever caused Descartes’ idea of God must itself be an infinite and perfect being because of premise 4 above.

Argument for the existence of the external world

Descartes then continues his process of intuition and deduction to argue that because God exists, his perception can be trusted. These perceptions are of an external world of physical objects and, because Descartes can trust his perceptions, he can trust that the external world and physical objects exist:

“there is in me a certain passive faculty of perception, that is to say of receiving and knowing the ideas of [physical objects]… these ideas are often presented to my mind without my contributing to it in any way, and indeed frequently against my will. This faculty must therefore necessarily be in some substance different from me… and this substance is either [physical objects]… or else it is God himself, or some other creature more noble than [physical objects]… But, God being no deceiver, it is manifest that he does not of himself send me these ideas directly, or by the agency of any creature… And accordingly one must confess that [physical objects] exist.”

– Descartes, Meditation 6

The key points are as follows:

- I have perceptions of an external world with physical objects

- My perceptions cannot be caused by my own mind because they are involuntary (Descartes’ argument for this is similar to e.g. Locke’s argument here)

- So, the cause of my perceptions must be something external to my mind

- God exists (see trademark argument above)

- If the cause of my perceptions is God and not the physical objects themselves, then God has created me with a tendency to form false beliefs from my perception (because premise 1)

- But God is a perfect being by definition (see e.g. Descartes’ ontological argument) and so would not create me with a tendency to form false beliefs from my perceptions

- So, I can trust my perceptions

- So, given premises 1 and 7 above, I can know that an external world of physical objects exists

Problems

The Cartesian circle

A potential issue with Descartes’ overall approach here is that the reasoning is circular – it commits the fallacy of begging the question. This is a bit of an oversimplification but you could say Descartes’ argument is that:

- God exists and isn’t a deceiver because I perceive it clearly and distinctly

- and clear and distinct ideas can be trusted as true because God wouldn’t allow me to be mistaken about them

This isn’t a strong argument because it assumes clear and distinct ideas are true (1) in order to prove that clear and distinct ideas are true (2).

Possible response:

Descartes responds to this objection in the second and fourth set of objections and replies to Meditations. His response essentially rejects the characterisation of (2) above: The trustworthiness of clear and distinct ideas is not because of God. Instead, the trustworthiness of clear and distinct ideas – such as the cogito – is self-evident.

The concept of God is not innate

We can challenge Descartes’ trademark argument by rejecting the first premise and arguing that the concept of God is not innate. If the concept of God comes from experience, as Locke argues below, then Descartes’ argument is not entirely a priori and thus fails to establish rationalism.

Further, Descartes’ argument for the existence of the external world relies on his arguments for the existence of God. So, if Descartes’ arguments for God are not a priori, then neither is his argument for the existence of the external world.

So, if Descartes’ arguments rely on a posteriori concepts, then they do not establish synthetic truths a priori and thus fail to prove rationalism is correct.

Hume’s Fork

Another way to challenge Descartes’ arguments for rationalism is by applying Hume’s Fork. David Hume (1711 – 1776) was an empiricist and argued that there are only two kinds of knowledge (judgements of reason): relations of ideas and matters of fact.

| Relations of ideas | Matters of fact |

| “either intuitively or demonstratively certain” (i.e. an analytic truth) | “The contrary of every matter of fact is still possible; because it can never imply a contradiction” (i.e. a synthetic truth) |

| “discoverable by the mere operation of thought, without dependence on what is any where existent in the universe” (i.e. they are known a priori) | Can’t be established purely by thought and thus require empirical observation to establish their truth (i.e. they are known a posteriori) |

| The key feature of a relation of ideas is that it cannot be denied without a contradiction (e.g. ‘triangles do not have 3 sides’ is logically contradictory and inconceivable to the mind) | The key feature of a matter of fact is that there is no logical contradiction in it being false (e.g. ‘grass is not green’ is false but it is not logically contradictory and so can be conceived of in the mind (e.g. as red grass)) |

We can argue that Descartes’ arguments rely on matters of fact. But, according to Hume’s Fork, matters of fact can only be known a posteriori. Thus, if Hume’s Fork is correct, then it shows that Descartes’ arguments are not entirely a priori and thus fail to establish rationalism.

Applied to the trademark argument, we could say there is no contradiction that results from denying the causal adequacy principle (“the cause of an effect must be as real as the effect”). For example, we can coherently conceive of a cause with less reality than the effect (e.g. developing a physical bruise after getting punched by a non-physical ghost). This shows that premise 4 can only be known as a matter of fact and not a relation of ideas, and thus can only be known a posteriori. So, Descartes’ trademark argument is not entirely a priori and thus fails to establish rationalism.

Similarly, we can argue that Descartes’ argument for the existence of the external world also relies on a posteriori matters of fact. For example, premise 2 states that “my perceptions cannot be caused by my own mind because they are involuntary” but there is no contradiction that results from denying this claim. For example, dreams are caused by one’s own mind but are nevertheless involuntary and so we can coherently imagine that this premise is false. Thus, Descartes’ argument for the existence of the external world is not entirely a priori either and so fails to establish rationalism.

Innate knowledge

Innate knowledge is knowledge you’re born with and so doesn’t require experience (a posteriori) to be known. In other words, innate knowledge is a priori knowledge.

The debate between empiricism and innatism is about whether we have innate knowledge or not:

- Innatism says we have some innate knowledge

- Empiricism says we do not have any innate knowledge

It’s also important to note that the kind of knowledge we are considering in this innate knowledge discussion is innate propositional knowledge. It’s uncontroversial, for example, that babies are born with innate ability knowledge, such as knowing how to breathe.

Plato: Meno

Plato argues that all learning is a form of recalling knowledge from before we’re born. So, in other words, we’re born with innate knowledge and we just need to remember it.

Plato argues that all learning is a form of recalling knowledge from before we’re born. So, in other words, we’re born with innate knowledge and we just need to remember it.

To prove his theory, Plato shows how Meno’s slave – a boy who has never been taught geometry – is able to understand a geometry proof. The key facts of the argument are as follows:

- Socrates draws a square on the ground that is 2 feet x 2 feet

- Meno’s slave agrees its area is 4 square feet

- Socrates then draws another square on the ground that has an area of 8 square feet

- Socrates then asks: What are the lengths of the sides?

- Meno’s slave incorrectly guesses 4 feet initially (the area would be 16 square feet, not 8)

- But Socrates asks Meno’s slave a series of questions

- Meno’s slave answers the questions correctly and realises that the sides of a square with an area of 8 square feet will be equal to the diagonal of the original 2 feet x 2 feet square

If this doesn’t make sense, the 18 second video below is a much easier way of visualising Socrates’ proof. Notice that the green square is twice the area of the red square and that the sides of the green square are equal to the diagonal of the red square.

Again, Meno’s slave has never been taught geometry, i.e. he has no experience of geometry. Despite this, Meno’s slave is able to correctly answer Socrates’ questions (or at least correct his mistakes). Given that Meno’s slave has no experience of geometry, his correct knowledge here must be innate.

Possible response:

You could argue that the slave boy instead used reason to work out the correct answer, rather than that he innately knew the answer beforehand – especially since the slave gives a bunch of wrong answers before eventually giving the correct answer.

Further, the empiricist might argue that asking questions, as Socrates does in this dialogue, is itself a form of teaching.

Leibniz: Necessary Truths

“The mind is capable not merely of knowing [necessary truths], but also of finding them within itself. If all it had was the mere capacity to receive those items of knowledge… it would not be the source of necessary truths… For it cannot be denied that the senses are inadequate to show their necessity”

– Leibniz, New Essays on Human Understanding, Bk 1

Gottfried Leibniz argues that our knowledge of necessary truths must be innate.

| Contingent truth | Necessary truth |

| What is the case | What must be the case |

| Could have been false in some other possible world | True in every possible world |

| E.g. “this website exists” is true but it would be false in some other possible world where I didn’t make it | E.g. “2+2=4” is true in every possible world – it must always be true |

A posteriori experience can only tell us about specific instances. For example, experience can tell us that adding these 2 apples to these 2 two apples gives us 4 apples in this particular instance.

But no amount of experience can tell us how things must be (because even if you add apples 100000 times, you never know what will happen the 100001st time). And yet we do know that it must always be true that “2+2=4”. We know that there will never be an instance where you add 2 apples to 2 apples and get 5 apples because “2+2=4” is a necessary truth.

The example of a necessary truth Leibniz often uses is noncontradiction: That “It is impossible for something to be and not be at the same time”. Like “2+2=4”, we know that this is necessarily true – that we will never experience something that both is and isn’t simultaneously.

Again, though, experience only tells us how things are (what’s contingently true) not how they must be (what’s necessarily true). And yet we know that noncontradiction must always be true. So, Leibniz argues, knowledge of necessary truths can’t come from experience – it must be innate.

Problems

John Locke: Essay Concerning Human Understanding

John Locke provides several arguments against innate knowledge.

No universal consent

Firstly, he argues that if we did have innate knowledge then every human would have such knowledge – that there would be universal consent to it:

“this argument of universal consent, which is made use of to prove innate principles, seems to me a demonstration that there are none such: because there are none to which all mankind give an universal assent… “Whatsoever is, is,” and “It is impossible for the same thing to be and not to be”; which, of all others, I think have the most allowed title to innate… But yet I take liberty to say, that these propositions are so far from having an universal assent, that there are a great part of mankind to whom they are not so much as known… For, first, it is evident, that all children and idiots have not the least apprehension or thought of them.”

– Locke, Essay Concerning Human Understanding, (Bk. 1, Ch. 2, §4-5)

So, for example, if the theorem of geometry that Meno’s slave realises in Plato’s example above was innate, then everyone would know it. But, Locke argues, “children and idiots” do not possess such knowledge – they don’t know these theorems of geometry, for example. Nor do they know Leibniz’s example above that “it is impossible for something to be and not be at the same time”.

Locke argues there are no examples propositions or beliefs that are held universally – no beliefs that everyone agrees on – and thus there are no examples of innate knowledge.

What’s more, says Locke, even if there were such examples of universal knowledge, this still wouldn’t prove this knowledge was innate because it could be explained in other ways – such as via simple and complex ideas acquired from experience.

“This argument, drawn from universal consent, has this misfortune in it, that if it were true in matter of fact, that there were certain truths wherein all mankind agreed, it would not prove them innate, if there can be any other way shown how men may come to that universal agreement, in the things they do consent in, which I presume may be done.”

– Locke, Essay Concerning Human Understanding, (Bk. 1, Ch. 2, §3)

So, in short:

- If innate knowledge did exist, it would have to be universal

- But there is no knowledge that is universal

- And, even if there were universal knowledge, this still wouldn’t prove that knowledge was innate.

Possible response:

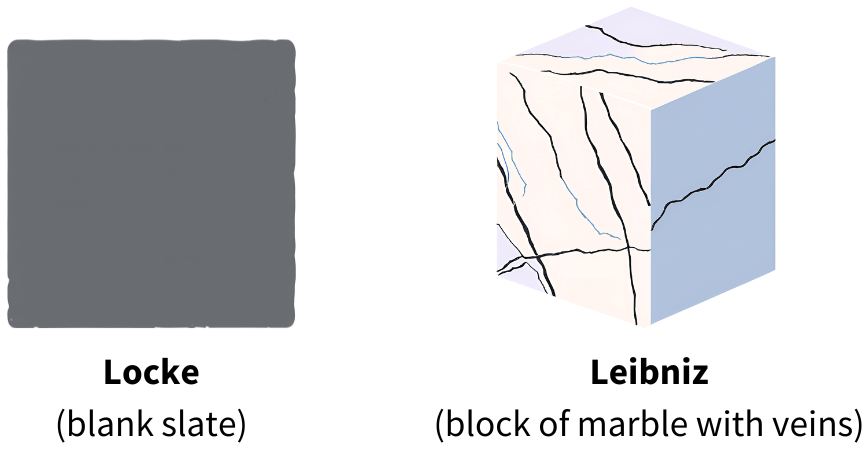

Leibniz argues that it’s possible to have innate knowledge and yet not be conscious of it. He illustrates this by drawing an analogy between the mind and a block of marble. Marble is not some neutral and homogeneous rock. Instead, it has veins running throughout it, and these veins give it a tendency to take a certain shape when struck. Although it requires a sculptor (i.e. experience) to reveal this shape, that shape is innately there in the marble from the start.

Leibniz argues that logical concepts such as identity (e.g. “a = a”) and noncontradiction (i.e. “it’s impossible for the same to be and not to be at the same time”) are innately present in the mind like veins in the marble. And even though a newborn baby can’t verbally articulate this knowledge, that doesn’t mean the knowledge isn’t there. Over time, we learn to recognise these concepts and make them explicit, but they were always there in the mind.

Tabula rasa

It follows from Locke’s rejection of innatism that all knowledge (and concepts) must come from experience. Where Leibniz compares the mind at birth to a block of marble with veins already in it, Locke says the mind at birth is a ‘tabula rasa’ – a blank slate.

Locke argues that the mind at birth contains no ideas, thoughts, or concepts. If you observe a newborn baby, for example, there is no evidence to suspect it has any knowledge – or any concepts – except those it has experienced, such as “hunger, and thirst, and warmth, and some pains”.

Instead, says Locke, all knowledge comes from two types of experience:

- Sensation: Our sense perceptions – what we see, hear, smell, taste, etc.

- Reflection: Experience of our own minds – thinking, wanting, believing etc.

Simple and complex ideas

Locke’s explanation of simple, complex, and abstract general ideas provides an account of how humans can form all knowledge – including complex concepts, such as the concept of God – from experience.

When I look at a clear sky, my sensation of blue might give me the simple concept of blueness. Likewise, when I’m outside in winter, my sensation of cold might give me the simple concept of coldness. A simple concept is just one thing like this.

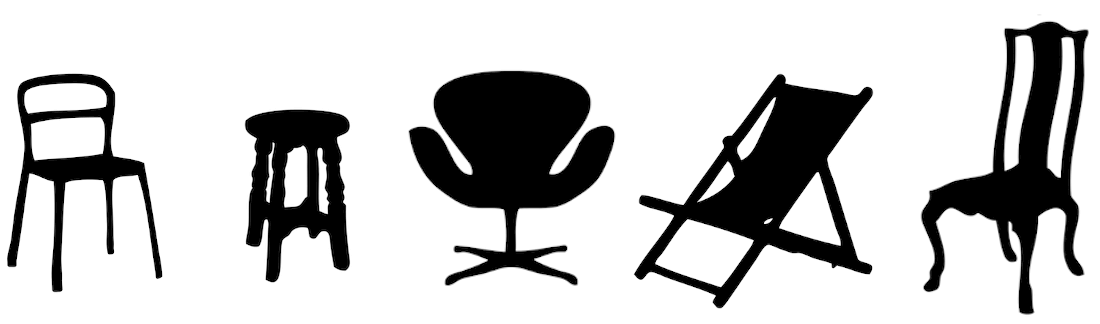

Complex concepts are made up of the building blocks of simple concepts. For example, my concept of the ocean could consist of both the simple concepts of blue and cold above. Pretty much everything is a complex concept made up of simple concepts to differing degrees – for example a chair might consist of many simpler concepts (e.g. brown, hard, wooden, small, etc.) and yet they all form the same thing: This chair. This chair is a complex concept because it contains many simpler concepts within it.

And complex ideas can go beyond specific instances of things (e.g. this chair) to form abstract ideas (e.g. chairs in general). For example:

- Chair #1 may be wooden and have four legs

- Chair #2 may be metal and have 3 legs

- Chair #3 may be a red plastic stool

Similarly, we form abstract concepts such as beauty or justice or God by abstracting from experience. For example, we see a beautiful lake, a beautiful painting, a beautiful person, etc. and over time we abstract the common features from these experiences to form the abstract concept of beauty.

The point of all this: Locke’s account here aims to show how all concepts and knowledge – from simple to complex – can be explained as coming from experience in some way. And so, if we can explain all knowledge and concepts using experience only, we don’t need innate knowledge.