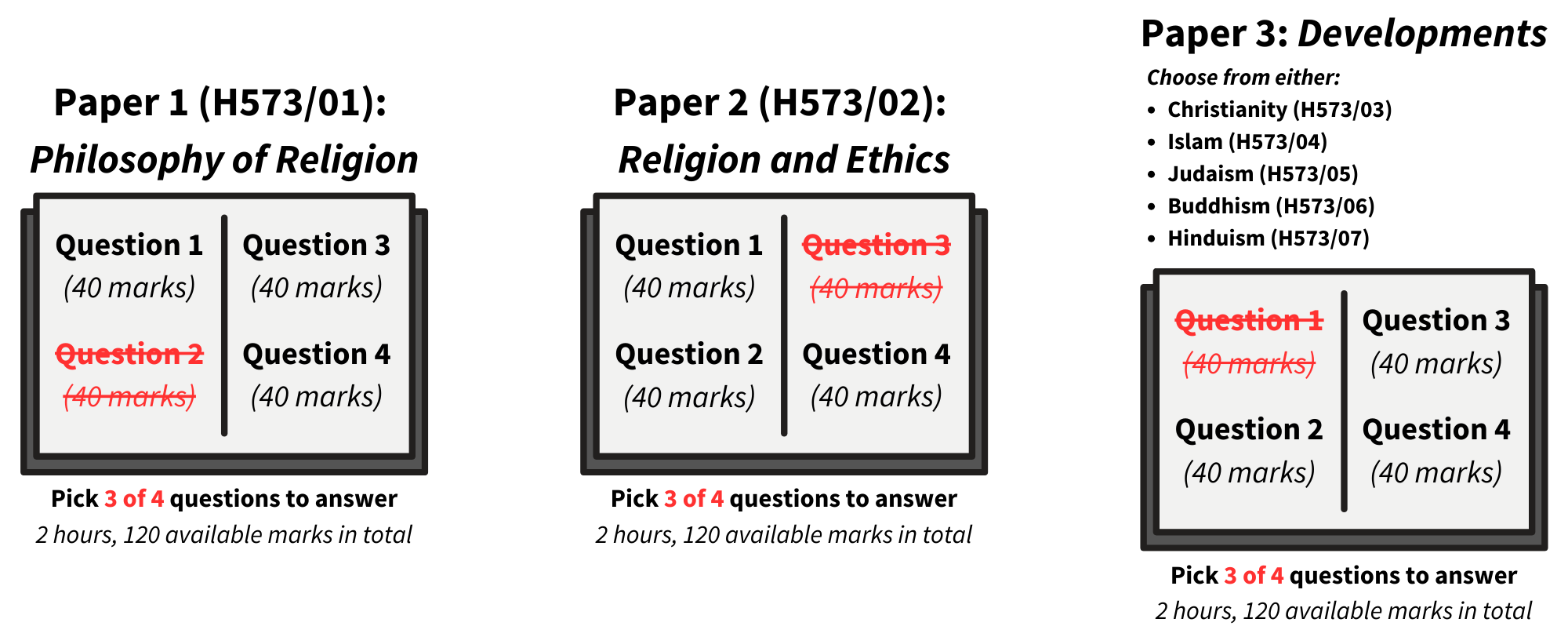

OCR Religious Studies – Developments in Christianity

The Developments in Christian Thought section of the exam paper in OCR A Level Religious Studies (H573/03) contains essay questions on the following topics:

- St. Augustine’s teachings on human nature (including the Fall, original sin, and grace)

- Christian views on death and the afterlife (including heaven, hell, purgatory, and election)

- Knowledge of God (including natural knowledge and revealed knowledge)

- The person of Jesus Christ (as son of God, a teacher of wisdom, or political liberator)

- Sources of Christian moral principles (including the Bible, the church, and reason)

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s teachings on ethics and Christian moral action

- Christianity teaching on other religions (exclusivism, inclusivism, and pluralism)

- Christian views on gender (including responses to secular views and feminist theology)

- The challenge of secularism for Christianity

- Liberation theology (and its relationship to Marxism)

St. Augustine on human nature

Human nature is the idea that human beings have a core essence – that, despite minor differences, all humans ultimately have the same general character. St. Augustine’s view of human nature has been highly influential on Christian theology, and in the 5th Century became the orthodox view over alternative theological interpretations such as those of Pelagius. Augustine taught that humans were initially made in God’s image and lived in perfect harmony with God but, after the Fall in the Garden of Eden, human nature was corrupted by original sin. Despite this sinful nature, Augustine says, God’s grace means people can sometimes choose good and be saved.

The Fall

The Fall refers to the story in the Bible where Adam and Eve disobey God and eat from the tree of knowledge. It also comes up in the philosophy of religion topic with the problem of evil:

The Fall refers to the story in the Bible where Adam and Eve disobey God and eat from the tree of knowledge. It also comes up in the philosophy of religion topic with the problem of evil:

- God created Adam and Eve, the first humans, “in his own image” (Genesis 1:27).

- Adam and Eve lived in the Garden of Eden: A paradise created by God where they would have everything they needed, where there was no pain or danger, and where God lived alongside them.

- “God commanded the man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat: But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it” (Genesis 2:16-17).

- A serpent (Satan) tempts them to disobey this command. Eve eats from the tree of knowledge, and gives some to Adam, who also eats (Genesis 3:6).

- Adam and Eve then realise they are naked, feel shame, and hide from God.

- God realises they have eaten from the tree of knowledge and, as punishment, banishes them from the Garden of Eden into our fallen world.

Original Sin

Augustine interprets the Fall as changing human nature. Before the Fall, human nature was such that our will was perfectly aligned with reason. However, after the fall, our will becomes corrupted by our desires – particularly sexual desire.

For example, before the fall, Adam and Eve were married – but as friends and without sexual lust. They would have had the pleasure of sex, but having sex would be a reasoned decision and fully under the control of the will. However, after the fall, sexual desire is no longer under the control of the will – we lust after random people in the street, for instance. Augustine’s word for this disharmony between the will and our desires is concupiscence.

Because all humans (except Jesus) are descendants of Adam, they inherited Adam’s concupiscence and tendency towards sin. This is known as original sin – that humanity inherited Adam’s sinful nature.

God’s grace

Because of original sin, human nature is ruined. Everyone – from the moment they are born – has a tendency towards sin that is beyond the control of their will. As such, no matter how much we resist temptation and try to act morally, we can never truly be good. Augustine describes humanity as a massa damnāta – a damned species.

Despite the flawed nature of humanity, God’s omnibenevolence (see the philosophy of religion page for a reminder of this term) means He provides some people with grace. Grace is when God acts on people to make them choose good and have faith in Jesus. God’s grace means that some people can still go to heaven (even though they don’t deserve it) and be saved from hell.

Grace is not something we can earn or that we have control over – it’s a gift given by God. It is only by God’s grace – not our own actions – that we can be saved. Augustine thus believes in limited election.

AO2 evaluation: Augustine on human nature |

|---|

Issues for St. Augustine’s view of human nature:

|

Death and the afterlife

This topic is about Christian views of what happens after we die – with particular reference to Jesus’ parable of the sheep and the goats in Matthew 25:31-46:

- Judgement: “And before him shall be gathered all nations: and he shall separate them one from another, as a shepherd divideth his sheep from the goats: And he shall set the sheep on his right hand, but the goats on the left.” (Matthew 25:32-33)

- Heaven: “Then shall the King say unto them on his right hand, Come, ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world:” (Matthew 25:34)

- Hell: “Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels:” (Matthew 25:41)

There are differing views on the afterlife within Christianity. This parable evokes images of heaven and hell. Should we understand them as literal, spiritual, or symbolic places? Are they eternal or finite? Is there a third option – purgatory? There is also the question of election – who goes where and why.

Heaven and hell

The literal interpretation

The typical view of heaven and hell are as literal, physical, places where you go when you die:

The typical view of heaven and hell are as literal, physical, places where you go when you die:

- Heaven is this perfect paradise where you have everything you could ever want and experience perfect happiness. Literal interpretations often evoke images of physical, earthly, pleasures such as dancing, celebrating with family and friends, and eating.

- Hell, in contrast, is the exact opposite: A place of “fire and brimstone” where people experience terrible pain and suffering. Literal interpretations often evoke images of physical, bodily, torture.

Revelation 21 appears to describe heaven and hell in literal terms: Earth is transformed into a heavenly ‘New Earth’ where God lives among the people but where sinners are “consigned to the fiery lake of burning sulfur”. A New Jerusalem is described that is decorated with jewels and gold and has physical dimensions: “12,000 stadia in length” and with walls “144 cubits thick”.

These literal interpretations are typically thought of as permanent. If you’re let into heaven, you live there forever more. But if God sends you to hell, you can never escape. The idea that heaven and hell are permanent and inescapable is in line with Jesus’ description at the end of the parable of the sheep and the goats where those on the left hand “shall go away into everlasting punishment: but the righteous into life eternal.” (Matthew 25:46).

Spiritual interpretations

Alternatively, we may think of heaven and hell as spiritual states of the soul.

These spiritual states would, presumably, be radically different to our experience while alive on earth. For one thing, you wouldn’t have a physical body. Instead, your non-physical soul would leave your body behind when you die:

- Heaven would be a blissful and pleasant state, greater than any happiness attainable on earth. Aquinas described the beatific vision where we are directly in God’s presence and meet Him face-to-face. While living as finite and imperfect human beings, we can never truly appreciate God’s infinite and perfect nature. But, after death, we can experience direct union with God. Only then can we truly comprehend His perfect and infinite nature, and this experience would be of perfect and infinite happiness.

- Hell, in contrast, would mean total separation from God. “Fire and brimstone” are not literal descriptions of a physical place, but instead represent the spiritual suffering that would come from being completely alienated from God’s goodness. Many Christians who take this view see hell as a state people commit themselves to rather than something God actively inflicts on us: By choosing sin and not repenting, we choose to turn away from God and end up in hell.

Like the literal interpretation, these spiritual interpretations are typically thought of as permanent. But, whereas a physical body only really makes sense within time, a non-physical soul could potentially exist outside of time. And so, the permanence of heaven and hell could potentially be eternal rather than everlasting (see the philosophy of religion page for a reminder of these terms).

Symbolic interpretations

Heaven and hell may also be interpreted symbolically as referring to states while alive on earth:

- If you choose not to follow God’s commandments and live a morally bad life – you lie, steal, cheat on your wife, abuse drugs, are lazy, and so on – your life will unravel and become hell. For example, your friends and family will desert you, you may become an addict, suffer health problems, have no money etc. Hell, then, is not a literal punishment that God inflicts on us but a natural consequence of living a bad life.

- On the other hand, if you do follow God’s commandments and be a good person – you care for other people and treat them well, tell the truth, work hard, stay healthy, and so on – then you will experience heaven: A happy life, friends and family who love you, rewarding work and material comfort, and so on. Here, heaven is not a literal place but the natural consequence of living a good life.

Unlike the literal and spiritual interpretations, this symbolic interpretation is not permanent – at least not literally. It symbolises a state of being during the finite time we are alive on earth.

Purgatory

Purgatory is a state in between a person’s earthly life and heaven. It is mainly a Catholic belief.

A common misconception of purgatory is as a kind of crossroads prior to judgement where a person can still act to change whether they go to heaven or hell. However, the orthodox interpretation is that judgement has already happened when a person is in purgatory. The idea is that a person in purgatory is destined for heaven but are still not worthy of meeting God – even if they have been pretty good – without some sort of spiritual ‘cleansing’ first:

“All who die in God’s grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven.”

– Catholic Catechism #1030

Election

Election is about who God chooses to go to heaven:

- Limited election says only some people will go to heaven

- Unlimited election says that everyone can go to heaven but it’s not necessary that everybody will

- Universal election says everybody necessarily will go to heaven

Limited election

Limited election is the view that God has chosen only some people to go to heaven but not others – that there’s a limited number of places.

Augustine’s account of grace above supports limited election because grace is something given by God, not something we have control over. So God has already decided who will receive his grace and be saved.

In the 1500’s, John Calvin built on Augustine’s view. Calvin rejected free will and argued that God has control over everything, including our actions and spiritual destiny. This led Calvin to the conclusion of double predestination: God created some people to go to heaven and created some people to be sent to hell.

Unlimited election

Unlimited election is the view that everyone can go to heaven but that it’s possible (in theory) that some people may not due to their choices in life.

Karl Barth argued that Jesus’ work on the cross means all humans can be saved. God’s choice of who to save isn’t made at an individual level as limited election says – it isn’t that God picks some humans but rejects others. Instead, God’s choice was made at a human level – to come to earth in Jesus and take on humanity’s sins. Jesus is the one who elects and Jesus died for the sins of all humanity so in theory all humans can be saved.

The key difference between unlimited election and universal election is that unlimited election emphasises God’s sovereign choice to save all humans – that God didn’t have to save humanity but chose to do so in Jesus. In contrast, universal election emphasises God’s omnibenevolence and suggests that it would contradict God’s omnibenevolence if God didn’t ensure that everybody necessarily is saved.

Universal election

Universal election is the view that everyone must go to heaven – at least eventually.

John Hick’s soul-making theodicy from the philosophy of religion page is an example of universalism. Hick argues that our purpose in life is spiritual development – the end goal of which is to freely choose to follow in God’s ways and reconcile with Him (i.e. heaven). Hick argues that it would be a logical contradiction of God’s omnibenevolence for God to allow anyone to suffer forever. As such, Hick sees hell as a temporary place where we continue to exercise our free will until we change. This might take some people a very long time, but ultimately everyone will necessarily learn to choose good, escape hell, and reach heaven.

AO2 evaluation: Christian views on the afterlife |

|---|

Issues for Christian views of heaven and hell:

|

Issues for Christian views of election:

|

Knowledge of God

This topic is about the ways we can know of God’s existence and character. Broadly, there are 2 different categories:

- Natural knowledge is when we come to know God by ourselves through human faculties such as observation, reason, or an innate sense of the divine.

- Revealed knowledge is when God explicitly shows Himself to us in some way, such as by sending Jesus to earth and through His word in the Bible.

Pretty much all Christians agree that natural knowledge alone is not sufficient to properly know God. But there are many different views within Christianity on the importance of natural knowledge and also the authority that should be given to different forms of revealed knowledge.

Natural knowledge

In natural theology, a person uses their own capacities to attempt to know and understand God. Proponents of natural theology would say that even if someone had never heard of the Bible or Jesus, they could still gain some knowledge of God’s existence and character through human faculties such as observation, reason, and an innate sense of the divine.

An innate sense of the divine (sensus divinitas)

The 16th century Protestant theologian John Calvin argued that all humans are born with a sensus divinitas – i.e. an innate ability to sense God:

“That there exists in the human minds and indeed by natural instinct, some sense of Deity, we hold to be beyond dispute, since God himself, to prevent any man from pretending ignorance, has endued all men with some idea of his Godhead, the memory of which he constantly renews and occasionally enlarges”

– John Calvin, The Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book 1 Chapter 3

Calvin argues that even people from remote tribes with zero exposure to Christianity have some idea of God. Calvin takes this to show that the sensus divinitas is an innate faculty given to all humans. As such, all humans are able to know of God – at least on a very basic level – even in the absence of revealed theology such as the Bible.

According to Calvin, we experience the sensus divinitas in the following ways:

- Conscience: The fact that we feel good when we do right and guilty when we do wrong is because we have an innate understanding of God’s goodness.

- Beauty: We appreciate the beauty of creation – e.g. the beauty of the stars above and the complexities of the human body – because this beauty serves “as a kind of mirror, in which we may behold God, though otherwise invisible.”

- Intellectual capacity: We can use our capacity for reason to recognise God’s existence – see below for examples.

Reason and observation

Much of St. Thomas Aquinas‘ theology that we’ve covered elsewhere in the course is based on rationality and reason. For example:

- His cosmological arguments (the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd ways) reason from observations about cause, effect, necessity, and contingency to the conclusion that God exists.

- His teleological argument (the 5th way) reasons from the observation that things act according to a purpose as though designed to the conclusion that God exists.

- His ethical theory of natural law reasons from observations about the purpose/telos of things to conclusions about God’s plan and what God considers to be good.

There are no such arguments made in the Bible (at least not explicitly). And so, Aquinas is also an advocate of natural theology; he thinks we can understand – at least partially – God’s existence and character by observing the world around us and applying our capacity to reason.

However, Aquinas doesn’t say that reason alone definitively and conclusively proves God’s existence because this would remove the need for faith. Instead, he says, such arguments – and reflection on the world around us through reason – support faith. Aquinas’ view here is in line with Pope John Paul II’s letter Fides et Ratio, which says: “Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth”.

Revealed knowledge

Although many Christians believe natural theology may provide some knowledge of God, the orthodox view – held by both Calvin and Aquinas – is that natural knowledge alone is not enough to know God. Some argue this is because the Fall damaged humanity’s capacity for reason such that we can never fully know God by ourselves. Instead, Christians believe that proper knowledge of God requires revealed theology.

Revealed knowledge is when God deliberately chooses to show himself to us in some way. For Christians, the most significant example of such revelation is God coming to Earth in the person of Jesus Christ. Other sources of revealed knowledge include faith and grace, the Bible, and the church.

Faith and grace

For most Christians, belief in Christianity and Jesus is primarily a matter of faith rather than something that is conclusively proved by reason or observation.

Aquinas, for example, saw faith as a conscious decision to believe in something even though it is uncertain. Although reason provides some idea of God’s existence and character, God is ultimately beyond comprehension and so it requires a ‘leap’ of faith to go from what reason and observation tell us to proper belief in Christianity. This leap of faith distinguishes religious belief from belief in science, for example. Once a person makes this leap of faith, their faith is affirmed and strengthened by God’s grace and the Holy Spirit.

Like Aquinas, Calvin sees faith as foundational to Christianity. But where Aquinas saw a fairly large role for reason, Calvin argued that the Fall corrupted the human mind so badly that it is “readily inclined to every kind of error”. As such, Calvin argued that proper knowledge of God (and of morality) must be founded in faith and obedience:

“it is impossible for any man to obtain even the minutest portion of right and sound doctrine without being a disciple of [the Bible]… For not only does faith, full and perfect faith, but all correct knowledge of God, originate in obedience.”

– John Calvin, The Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book 1 Chapter 6

For Calvin, like Augustine, such faith is purely a matter of grace: It is not something we have control over but is instead something that is given to us by God.

The Bible

For some Christians, the Bible is seen as the direct, perfect, and infallible word of God. For others, the Bible is seen as a record of God’s revelation and interaction with humanity – but a record ultimately written by (finite and fallible) human beings.

For some Christians, the Bible is seen as the direct, perfect, and infallible word of God. For others, the Bible is seen as a record of God’s revelation and interaction with humanity – but a record ultimately written by (finite and fallible) human beings.

Either way, Christians believe the Bible is a record of God’s revelation to humanity. It describes various instances where God reveals himself to humanity. Examples of this include:

- In the Old Testament, God speaks to various prophets directly. For example, in Exodus, God communicates the 10 Commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai and gives him physical stone tablets on which they are written.

- The Gospels of the New Testament (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John) tell the story of God coming to earth in the person of Jesus. In Matthew 3:17, God speaks from heaven and says of Jesus “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.”

- Later books of the New Testament describe the spread of Christianity after Jesus’ death and resurrection, including the formation of the Church. In Acts 9, Jesus appears to Saul and says “Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?”, after which Saul converts to Christianity and becomes Paul the apostle.

Revealed knowledge of God in Jesus Christ

The Bible tells the story of Jesus, which is really the crux of Christianity and the most important part of God’s revelation for humanity. As always, there are different interpretations, but most orthodox interpretations say something like:

- Human nature was damaged in the Fall and sin created a gap between humans and God

- God came to Earth in the person of Jesus and died for the sins of humanity

- Jesus’ sacrifice bridges this gap between humans and God, completing God’s plan for humanity

The Church

For Catholics, the Church is a gift given by God and is in some sense a continuation of God’s revelation that holds great authority. Examples of this include:

For Catholics, the Church is a gift given by God and is in some sense a continuation of God’s revelation that holds great authority. Examples of this include:

- The Magisterium of the Church means it is able to give authoritative interpretations and applications of the Bible.

- Sacred tradition includes teachings and practices handed down from Jesus and the apostles by word of mouth. Whereas Protestants typically say the Bible alone is sufficient, Catholics recognise Bible + sacred tradition.

- The Sacraments – rituals including baptism, marriage, and the Eucharist – are seen as signs of God’s grace. For example, when the bread and wine are consecrated during Eucharist, Catholic tradition says they are transubstantiated – changed in substance – into the body and blood of Jesus.

In contrast, Protestants typically see the role of the Church as simply a means to direct people towards God’s revelation in the Bible (which is the sole authority). Although people within the Church (e.g. vicars) may help people understand and interpret the Bible, Protestants reject the notion that the Church has any special ability to, for example, give authoritative interpretation of it.

AO2 evaluation: Knowledge of God’s existence |

|---|

Issues for natural knowledge of God’s existence:

|

Issues for revealed knowledge of God’s existence:

|

The person of Jesus Christ

Jesus Christ is the central figure of the Christian faith. The orthodox Christian view of Jesus is that he is the divine son of God – fully God and fully man simultaneously. However, even non-Christians who reject Jesus’ divinity may acknowledge that he was an important historical figure who challenged the powers of his day and liberated the marginalised and poor, or that he was a wise and influential teacher of morals. This topic examines these different characterisations of Jesus.

Jesus Christ is the central figure of the Christian faith. The orthodox Christian view of Jesus is that he is the divine son of God – fully God and fully man simultaneously. However, even non-Christians who reject Jesus’ divinity may acknowledge that he was an important historical figure who challenged the powers of his day and liberated the marginalised and poor, or that he was a wise and influential teacher of morals. This topic examines these different characterisations of Jesus.

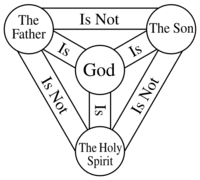

Jesus as the divine Son of God

Jesus is often referred to as the Son of God – but there are different interpretations of what this means and how Jesus (the son) relates to God (the father).

Modern Christian orthodoxy says that Jesus is God – they are one and the same. However, this wasn’t always the official view. In the centuries after Jesus’ death, various doctrines were proposed to resolve the apparently conflicting claims that Jesus was both God and human simultaneously:

- Adoptionism said Jesus was born an ordinary human but ‘adopted’ by God when baptised by John the Baptist. This view saw Jesus as having the same kind of status as the prophets of the Old Testament (e.g. Moses), albeit more important.

- Docetism said Jesus was fully God but taking the appearance of a human.

- Arianism said Jesus was less important than God because he was created by God (so Jesus would not be co-eternal with God).

These doctrines are now considered heresies (i.e. wrong according to mainstream orthodox Christianity). The orthodox view that Jesus and God are consubstantial (i.e. of the same substance) was decreed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD. The council defined Jesus as “truly God and truly Man.”

These doctrines are now considered heresies (i.e. wrong according to mainstream orthodox Christianity). The orthodox view that Jesus and God are consubstantial (i.e. of the same substance) was decreed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD. The council defined Jesus as “truly God and truly Man.”

Note: Modern Christian orthodoxy also adds the Holy Spirit as consubstantial with Jesus and God. This ‘trinity’ is one substance (one God) but three persons.

Jesus’ divine status is supported by his performing of miracles and, in particular, the resurrection.

Miracles

Jesus performs many miracles in the New Testament. John calls these miracles ‘signs’ (the implication being these signs point to Jesus’ divinity).

The syllabus mentions the following two Bible passages in particular with regard to Jesus’ miracles:

- In Mark 6:47-52, Jesus walks on water. Earlier in Mark 6, Jesus performed another miracle, feeding 5000 people with only 5 loaves of bread and 2 fishes. However, the disciples “still didn’t understand the significance of the miracle of the loaves” (Mark 6:52 NLT) until Jesus walked on water. The implication is that, after this second miracle of walking on water, the disciples finally recognised Jesus’ identity as God.

- In John 9:1-41, Jesus heals a man who was born blind. The Jewish authorities didn’t believe or want to accept this because it broke the Old Testament law of working on the Sabbath day, so they cast the blind man out. Jesus then asks the previously blind man “Dost thou believe on the Son of God?” (John 9:35), to which the blind man asks “Who is he, Lord, that I might believe on him?” (John 9:36), and Jesus responds: “Thou hast both seen him, and it is he that talketh with thee” (John 9:37). So, here, Jesus identifies himself as the Son of God.

These verses may be taken as evidence of Jesus’ divinity. There are many examples of people performing miracles in the Old Testament (e.g. Moses parting the Red Sea in Exodus), but these aren’t taken to show that the person is God. However, these verses imply not only that Jesus’ power to perform miracles comes from God, but that Jesus is God.

The resurrection

For Christians, Jesus’ death and resurrection is no ordinary miracle. It is the fulfilment of God’s plan for humanity and performed a function only God himself could perform.

Although there are minor differences between the four Gospel accounts, the key points of the story are:

- Jesus was crucified until dead

- Then buried in a tomb that was sealed with a boulder

- Three days later, the tomb was found to be empty

- Jesus then appeared to his followers and showed he had risen from the dead.

By most orthodox interpretations, Jesus’ death is seen as salvific: He died for the sins of all humanity. Before Jesus, humanity’s sinful nature was such that no human could ever truly know God and be saved. However, Jesus’ unique status as both God and man meant he could act as a mediator between humanity and God. Jesus’ death is seen as paying the ‘price’ of humanity’s sin, bridging the gap between humans and God that was created after the fall.

Only God (through the person of Jesus) could perform such work and save humanity. As such, Jesus’ resurrection is understood by Christians as evidence of his divinity.

Did Jesus see himself as divine?

The syllabus raises the issue of whether Jesus regarded himself as divine. The following are examples of Bible verses that can be used to support either side:

| Evidence suggesting Jesus did regard himself as divine | Evidence suggesting Jesus did not regard himself as divine |

| In several verses (e.g. John 8:58 below) Jesus refers to himself by the same name for God which was revealed to Moses in the Old Testament (YHWH/kyrios, which translates to “I am”). | Hick argues that it is mainly in the gospel of John that Jesus refers to himself this way. In the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), Jesus more commonly refers to himself as the “Son of Man”. |

| In John 10:30, Jesus says “I and my Father are one.” | In John 14:28, Jesus says “I go unto the Father: for my Father is greater than I.” |

| In John 8:58, Jesus says “Before Abraham was, I am.” This implies Jesus, unlike mortal human beings, has always existed. | Jesus often speaks to God in a way that implies he is separate from him. For example, during his crucifixion in Matthew 27:46 Jesus cries “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” |

Jesus as a teacher of wisdom

Even those who reject Jesus’ divine status as God may accept he was a profound teacher of wisdom.

In Islam, for example, Jesus is regarded as a prophet who performed many great miracles but Islam rejects the Christian account of the resurrection. Most importantly, Islam does not regard Jesus as God, but as a messenger of God.

Even among secular historians, it is fairly uncontroversial that Jesus was a real person who walked the earth during the time period described in the Bible. As such, atheist or agnostic readers may reject certain parts of the Bible (e.g. supernatural elements such as miracles) and yet still find great wisdom in the moral teachings of Jesus.

Some key themes in Jesus’ moral teachings are repentance and forgiveness. The syllabus focuses on two passages in particular: Matthew 5:17-48 (the Sermon on the Mount) and Luke 15:11-32 (the Prodigal Son).

The Sermon on the Mount

In Matthew 5, Jesus begins his famous Sermon on the Mount. In this sermon, Jesus describes an approach to morality that departs from the legalistic interpretation of Old Testament morality that was common at the time:

- Be righteous on the inside, not just the outside: Jesus affirms the importance of Old Testament law – “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.” (Matthew 5:17) – but suggests true righteousness is about more than just actions. For example, Jesus references the law “Thou shalt not kill” (Exodus 20:13) but takes it further in suggesting that anyone who is angry with another person also faces judgement (Matthew 5:21). Similarly, Jesus references the law “Thou shalt not commit adultery.” (Exodus 20:14) but takes it further in suggesting that “anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” (Matthew 5:28, emphasis added)

- Love everyone, even your enemies: Jesus reiterates the Old Testament verse that you should “love your neighbour” (Leviticus 19:18) but rejects the notion that this means you should “hate your enemy”. Instead, Jesus says you should “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 15:44).

- Forgive and don’t seek revenge: Jesus references the Old Testament adage that justice is “eye for eye, tooth for tooth” (Leviticus 24:20). However, Jesus rejects the idea that this means we should take matters into our own hands and seek revenge, saying: “If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well.” (Matthew 15:39-40).

The Prodigal Son

Luke 15 contains the parable of the prodigal son. This is a parable that illustrates God’s forgiveness and the importance of repentance:

Luke 15 contains the parable of the prodigal son. This is a parable that illustrates God’s forgiveness and the importance of repentance:

- A father has two sons, the younger of whom asks for his inheritance early (Luke 15:11-12)

- The younger son takes this inheritance and squanders it through “wild living” – think partying etc. (Luke 15:13)

- With no money left and starving, the younger son returns back to his father with the intention of apologising and working for his father as a servant (Luke 15:17-19)

- But when the father sees the younger son return, he runs to and embraces him and prepares a feast and gives him the best clothes

The standard interpretation of this parable is that God’s forgiveness is limitless – there is nothing we can do that is so bad that God will abandon us, as long as we repent from these sins. In this parable, the father represents God – the father could have been mad at the son for wasting his money, but instead is just happy that the son has returned. The father is happy because “my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found” (Luke 15:24 KJV).

Jesus as a political liberator

Jesus often clashed with the political and religious authorities of the day (politics and religion overlapped significantly during Jesus’ time). In these clashes, Jesus often took the side of the underdog – e.g. the poor or oppressed – against the political and religious authorities of the day. This supports the view of Jesus as a political liberator.

The Pharisees – the religious authorities of the day – were sticklers for Mosaic (Old Testament) law. They are often portrayed in the Bible as snobbish and hypocritical virtue signallers – following the letter of the law in a legalistic and pedantic way whilst ignoring the spirit of the law and truly worshipping God. Jesus’ actions and teachings on morality described above meant he often came into conflict with these Pharisaic authorities.

Examples of Jesus’ advocacy of outcast and marginalised groups include eating and drinking with “tax collectors and sinners” (Luke 5:30-32) and telling religious authorities that “the tax collectors and the prostitutes are entering the kingdom of God ahead of you” (Matthew 21:31). However, the syllabus mentions two Bible passages in particular as examples of Jesus as a liberator: Mark 5:24-35 (the bleeding woman) and Luke 10:25-37 (the good Samaritan).

The bleeding woman

Mark 5:24-34 tells the following story of a woman suffering from chronic bleeding:

- A woman had been suffering from chronic bleeding for 12 years and doctors were unable to help her (Mark 5:25-26)

- She hears of Jesus and goes to touch his clothes, believing that doing so will cure her bleeding (Mark 5:27-28)

- Touching Jesus’ clothes does indeed cure her (Mark 5:29)

- When Jesus realises what the woman did, he tells her that her faith is what cured her (Mark 5:34).

Why this is liberation: At the time, this woman would have been an outcast from society. Her bleeding would have made her ritually unclean according to Mosaic law (e.g. Leviticus 15:25), which meant she wouldn’t be allowed to worship in the synagogue. However, Jesus doesn’t judge her as an outsider or unworthy for this but instead commends her for her faith. This challenged the social and political order in that it suggests a person’s status or title in society – e.g. being a high-status Pharisee or Sadducee – is not important. Instead, a person’s faith is what matters.

The good Samaritan

In Luke 10:25-37, Jesus tells the following story in response to a challenge from a legal expert regarding the Mosaic law “Love your neighbor as yourself”:

- A man was attacked by robbers, who beat him up and left him for dead in the road (Luke 10:30)

- A priest saw the man, and crossed to the other side of the road and ignored him (Luke 10:31)

- A Levite also saw the man and did the same thing – crossed the road and ignored the injured man (Luke 10:32)

- But then a Samaritan saw the man and took pity on him, bandaged his wounds, helped him get to an inn where he could rest, and paid the innkeeper to look after him (Luke 10:33-35)

- Jesus asks the legal expert which of the three men “was a neighbour” – i.e. was truly following the law (Luke 10:36)

- The legal expert answers that it was the Samaritan – i.e. “The one who had mercy on him.” (Luke 10:37)

Why this is liberation: The Samaritans were the underdogs – an outcast and marginalised group for historical reasons – and yet Jesus takes their side against the more powerful and higher-status priests or Levites. Again, like the bleeding woman, the message here is that a person’s political or social status is not what’s important. Instead, what is important is a person’s faith and actions.

AO2 evaluation: The person of Jesus |

|---|

Issues for the view of Jesus as the divine Son of God:

|

Issues for the view of Jesus as a teacher of wisdom:

|

Issues for the view of Jesus as a political liberator:

|

Christian morality and ethics

This topic looks at ethics and morality – right and wrong – within Christianity. Although there is some overlap with parts of the religion and ethics page, the main issue here is where Christians should get their moral principles rather than specific discussions of what these moral principles are. The syllabus also includes the more specific topic of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s teachings on Christian moral action.

Christian sources of ethics

- Theonomous approaches see God’s word – the Bible – as the sole authority on ethics

- Heteronomous approaches use other sources – e.g. reason and the church – in addition to the Bible

- Autonomous approaches see the individual as responsible for ethical decision-making

The Bible as the sole authority

Theonomous approaches to Christian ethics see the Bible as the sole authority on morality.

Theonomous approaches to Christian ethics see the Bible as the sole authority on morality.

This is more a Protestant, rather than Catholic, view. During the reformation in the 16th Century, Protestant reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin argued that the Catholic Church was overruling and contradicting the Bible. The reformers argued that the Church’s authority should be rejected and faith should be sola scriptura (Latin meaning grounded in ‘scripture alone’).

Applied to morality and ethics, theonomous Protestant approaches reject the Church’s authority on ethical matters. Instead, the theonomous approach says the Bible contains everything necessary to live an ethical life. Church leaders may help Christians understand the Bible’s moral teachings, but these people have no authority themselves.

Theonomous approaches also reject reason as a source of ethical decision-making. As we saw above, John Calvin argued that human reason was so badly corrupted in the Fall that proper knowledge of God (and God’s will regarding morality) can only come from the Bible.

Advocates of theonomous approaches to ethics may point to verses such as the following in support of this view:

“All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness”

– 2 Timothy, chapter 3 verse 16 (NIV)

A combination of the Bible, the church, and reason

Heteronomous approaches to Christian ethics see other sources in addition to the Bible – such as the church and reason – as important for understanding right and wrong.

Heteronomous approaches to Christian ethics see other sources in addition to the Bible – such as the church and reason – as important for understanding right and wrong.

In Catholicism, the Church is given much greater significance as a source of ethics than in the Protestant tradition. For example, Catholic Catechism #2032 explicitly states:

“To the Church belongs the right always and everywhere to announce moral principles.”

According to Catholic teaching, this right to discern ethical principles comes from Jesus himself. In Matthew 16:16-19 (RSV), Jesus chose Peter – one of the 12 apostles – to have authority over the Church after his death, making Peter the first Pope. This authority is then passed on to each heir, so each Pope has authority that can be traced back to Jesus.

Heteronomous approaches may also acknowledge the use of reason as an important way for Christians to decide on moral issues. For example, in the religion and ethics topic, we saw Aquinas’ description of conscientia as the use of reason to apply general moral rules (precepts) to practical situations. According to Aquinas, the fact that we are made in God’s image gives us this capacity to reason about what is right and wrong – although the Fall means our own reasoning on ethics imperfect.

Agape/love as the sole principle

Autonomous approaches to Christian ethics say it is entirely up to the individual to work out what is right and wrong.

An example of such an autonomous approach to Christian ethics is Fletcher’s situation ethics from the religion and ethics topic. Fletcher argues that what is ethically good is, in each specific situation, to act in the most loving way. The Christian basis of this approach is Jesus’ teaching that:

“Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these.”

– Mark, chapter 12, verse 31 (KJV)

If there is ‘no greater commandment’ than this, then the individual’s judgement of what ‘loving one’s neighbour’ looks like should take priority over legalistic adherence to specific Bible verses (such as “Thou shalt not kill” (Exodus 20:13)) or strict adherence to ethical rules created by the Church (e.g. that euthanasia is wrong). In other words, it is up to individual Christians to use their capacities for reason to apply Jesus’ command to love your neighbour to each situation.

AO2 evaluation: Christian sources of ethics |

|---|

Issues for the theonomous (Bible only) approach to Christian ethics:

|

Issues for the heteronomous (mixed) approach to Christian ethics:

|

Issues for the autonomous (individual’s decision) approach to Christian ethics:

|

Christian moral action (Dietrich Bonhoeffer)

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a Christian theologian and pastor living in Germany before and during the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism. He opposed the Nazi Party and argued that the Church should see itself as separate from the State and government. With regards to ethics, Bonhoeffer emphasised moral action – it is not enough for Christians to simply believe, they have to do and sacrifice as Jesus’ example shows.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a Christian theologian and pastor living in Germany before and during the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism. He opposed the Nazi Party and argued that the Church should see itself as separate from the State and government. With regards to ethics, Bonhoeffer emphasised moral action – it is not enough for Christians to simply believe, they have to do and sacrifice as Jesus’ example shows.

Duty to God and duty to the state

Bonhoeffer saw a Christian’s ultimate duty as to God. In many cases, this will involve obeying the man-made laws of the land. However, if the state becomes corrupt and commands laws that go against God’s will, then civil disobedience is required.

In 1930’s Germany, some churches saw the state’s laws as an expression of God’s laws and aligned themselves with the Nazi Party and ideology. However, other churches opposed Nazi ideology and met to write the Barmen Declaration, which declared the Church as independent from the state. The Barmen Declaration became the foundation of a movement known as the Confessing Church.

Bonhoeffer was a key figure in the founding of the Confessing Church. He became head of a Confessing Church seminary (i.e. school for Church leaders) at Finkenwalde but, in 1937, it was declared illegal and closed down. Despite this, Bonhoeffer continued his seminary underground in an act of civil disobedience.

Moral action

For Bonhoeffer, ethics is about acting according to God’s will.

But God’s will isn’t something that we can understand through reason (the Fall corrupted reason too badly), nor is it something that can be distilled into a set of rules or beliefs taken from the Bible. Instead, Bonhoeffer argued, God’s will differs from situation to situation. And the only way we can know God’s will is through revelation – when God reveals himself to us directly – in the moment we act.

At Finkenwalde, Bonhoeffer encouraged students to read the Bible, discuss the Bible in groups, pray, and meditate to cultivate the spiritual discipline that would enable them to identify God’s will. By engaging in these activities and cultivating spiritual discipline, Christians can get a better sense of God’s will. Then, in the moment of action, the Christian must act according to what they sense is God’s will, knowing God will forgive them if they accidentally commit a sin in the process.

The Cost of Discipleship

In The Cost of Discipleship, Bonhoeffer distinguishes between ‘cheap grace‘ and ‘costly grace‘.

A core doctrine of Christianity is that Jesus died for and paid the price of humanity’s sins. But Bonhoeffer criticised the way this message was twisted by the Church to justify an easy and comfortable life without sacrifice. This is cheap grace – the belief that because “the account has been paid in advance; and because it has been paid, everything can be had for nothing.” For example, a person may get baptised as a Christian and then just carry on exactly as before – stealing, lying, and not making any sacrifices – believing that all their sins will be forgiven anyway.

In contrast, costly grace involves suffering and sacrifice. For Bonhoeffer, this is the proper understanding of grace because it involves engaging (at least to some degree) with the sacrifice and example of Jesus. Bonhoeffer would argue that the true Christian should be prepared to sacrifice everything for God’s grace – as in the parable of the hidden treasure:

“The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field. When a man found it, he hid it again, and then in his joy went and sold all he had and bought that field.”

– Mark, chapter 13, verse 44 (NIV)

A related concept mentioned on the syllabus is solidarity – the idea that Christians must live for other people rather than themselves. Bonhoeffer put his money where his mouth was in this regard: He moved back to Germany from America in 1939 in order to “live through this difficult period in our national history along with the people of Germany” (letter to Reinhold Niebuhr). Despite the danger, Bonhoeffer continued speaking out and acting against the Nazi regime and was imprisoned for it in 1943. He was executed on the 9th April 1945.

AO2 evaluation: Bonhoeffer and moral action |

|---|

Issues for Bonhoeffer’s teachings on Christian moral action:

|

Pluralism, exclusivism, and inclusivism

![]() Clearly, Christianity is not the only religion. This raises the issue of how Christians should regard people of these other religions. The theological question is about which teaching is the correct interpretation of Christianity. However, there are also questions about how these teachings fit within wider society, given that modern societies often contain a mix of people of different faiths that contradict Christianity.

Clearly, Christianity is not the only religion. This raises the issue of how Christians should regard people of these other religions. The theological question is about which teaching is the correct interpretation of Christianity. However, there are also questions about how these teachings fit within wider society, given that modern societies often contain a mix of people of different faiths that contradict Christianity.

Christian theology regarding other faiths

- Exclusivism is the view that Christianity is the only way to be saved.

- Inclusivism is the view that Christianity is the proper way to be saved, but that some non-Christians may also be saved.

- Pluralism is the view there are multiple – equally valid – ways to be saved, and Christianity is just one of these ways.

Exclusivism

Christian exclusivism says that Christianity is the only way to be saved.

Exclusivism makes sense in the context of some of the other Christian teachings we’ve looked at here. For example, if Augustine’s teachings on human nature are correct, then all humans are doomed without Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross – no matter how good a life they live. Orthodox Christianity teaches that it is Jesus’ sacrifice (and our acceptance of it) alone that redeems us, not our actions. As such, this interpretation leaves no room for salvation except through Jesus.

Supporters of Christian exclusivism will also point to the following verse to support exclusivism:

Jesus saith unto him, I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me.

– John, chapter 14 verse 6 (KJV) – emphasis added

Inclusivism

Christian inclusivism says that Christianity is the normative – i.e. the right or correct – way to be saved, but that anonymous Christians – i.e. people who are not Christians but are seeking the truth and in theory open to God’s grace – may also be saved.

Inclusivism makes sense when you consider that many people throughout history wouldn’t have even heard of Christianity and so would never have been able to explicitly accept Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. Catholic theologian Karl Rahner also makes the following points in support of inclusivism:

- Heroes of the Old Testament – such as Abraham and Moses – would surely be saved. But they wouldn’t have been able to accept Jesus’ sacrifice because they lived before Jesus was even born.

- In Acts 17, Paul travels to Athens and talks with people who haven’t yet heard about Jesus. Paul sees an altar inscribed “To The Unknown God” and tells the people of Athens that this ‘unknown’ God they worship is, in fact, the Christian God. Rahner’s interpretation of this is that the people of Athens were doing the right thing up to that point based on the information they had available – they were anonymous Christians – and could be saved. But, once presented with the Christian message by Paul, their ignorance would no longer be an excuse and they would have to accept Jesus’ sacrifice in order to be saved.

Pluralism

Christian pluralism says there are many ways to be saved, and that Christianity is just one of these ways.

A parable often used to illustrate pluralism is the blind men and the elephant: A group of blind men, who have never encountered an elephant, try to learn what an elephant is by touching it. Each man touches a different part of the elephant’s body – one its tusk, one its leg, and so on – and so each man has a different image of the elephant in their mind. In some way, all these ideas are accurate, but they are also limited in various different ways. In this parable, the elephant represents God, and the different men represent different religions.

A parable often used to illustrate pluralism is the blind men and the elephant: A group of blind men, who have never encountered an elephant, try to learn what an elephant is by touching it. Each man touches a different part of the elephant’s body – one its tusk, one its leg, and so on – and so each man has a different image of the elephant in their mind. In some way, all these ideas are accurate, but they are also limited in various different ways. In this parable, the elephant represents God, and the different men represent different religions.

Pluralism makes sense in the context of a multicultural, multi-faith, society. John Hick makes the following points in support of pluralism:

- There are equally good (and bad) people of all religions, which suggests that Christianity does not have a monopoly on morality. (Hick became a pluralist partly as a result of living in multi-faith Birmingham).

- Religious experiences are common to people from different faiths all over the world. And like William James (see the philosophy of religion notes for a recap), Hick believes people interpret these religious experiences differently according to the cultural beliefs of their society.

- Immanuel Kant distinguishes between the noumenon (i.e. the thing itself) and the phenomenon (i.e. how we experience the thing). We can never experience the noumenon itself, only the phenomenon. Applied to religion, Hick says different religions are different phenomenal ways of experiencing the same noumenon (i.e. God).

AO2 evaluation: Theology of religious pluralism |

|---|

Theological issues for exclusivism:

|

Theological issues for inclusivism:

|

Theological issues for pluralism:

|

Christian pluralism and society

If you were a Christian in Medieval England, for example, chances are you would never even encounter a person of a different faith. But in the modern day, immigration, globalisation, and technological advances in transportation and communication mean Christians will interact with many people from many different faiths – whose beliefs may directly contradict theirs – on a regular basis. The syllabus mentions two Christian responses to this issue in particular – Redemptoris Missio and Sharing the Gospel of Salvation – as well as the Scriptural Reasoning Movement.

Christian Responses

Redemptoris Missio, 55-57

Redemptoris Missio – Latin for ‘the Mission of the Redeemer’ – is a letter written by Pope John Paul II in 1990 on the role of Catholics and the Catholic Church in a multi-faith world:

- “Inter-religious dialogue is a part of the Church’s evangelizing mission” and is an expression of the Church’s mission ad gentes (i.e. its mission to preach the Gospel of Jesus to the world).

- The Church acknowledges “whatever is true and holy” in other religious traditions and says that “the followers of other religions can receive God’s grace and be saved by Christ” but “the Church is the ordinary means of salvation and that she alone possesses the fullness of the means of salvation.” (note: this is an inclusivist stance)

- Dialogue should be “based on hope and love” and Catholics who engage in such dialogues should be respectful and understanding to people of other faiths whilst remaining “consistent with their own religious traditions and convictions”.

Sharing the Gospel of Salvation

Sharing the Gospel of Salvation is a 2010 document issued by the Church of England on the role of Christians to proclaim the “unique revelation of God in Jesus Christ” in a multi-faith Britain:

- The document affirms an inclusivist position (sections 85 and 86) while still maintaining the centrality of Christ for salvation.

- Evangelising “is not an exercise in the selling of a product in a competitive marketplace of religions or philosophies, it is proclamation” – Christians should embrace inter-faith dialogue, speak proudly of their beliefs, and invite others to join them, but must avoid “bullying or manipulative” tactics in their proclamation.

- This proclamation “requires some combination of word and deed” – Christians must also walk the walk and live an authentically Christian life, which may inspire others to follow.

- aaaaa

The Scriptural Reasoning Movement

The scriptural reasoning movement started among a group of Jewish scholars studying Judaism’s sacred texts. But given the shared (Abrahamic) history of Judaism with Christianity and Islam, the group expanded to include Christians and Muslims. The point of the group’s meetings wasn’t to try and convert each other, but to develop a deeper understanding of their own and the other religions. These meetings gave rise to a general practice known as scriptural reasoning:

- Meetings typically focus on a particular topic or theme (for example marriage or parenting)

- Members from each of the different religions take turns reading passages from their sacred scriptures on this topic or theme

- The members discuss each others’ readings from the perspective of their own faith

The goal of these meetings is explicitly not to convert those of other faiths. Nor is it about reaching a mutual agreement. Instead, the goal is to develop better understanding of each other’s faith and beliefs. The method emphasises respect and openness, with the different faiths being seen as equally valid.

AO2 evaluation: Religious pluralism and society |

|---|

Wider societal issues regarding religious pluralism:

|

Christian views on gender

This topic examines Christian views on gender. Social attitudes towards women have changed since the era in which the Bible was written and so the societal question is about possible conflict between traditional Christian views on gender and modern society’s views on gender. Then the theological issues are about feminist interpretations of the Bible and Christianity.

Gender and society

Christian teaching on gender roles

Christian teaching on gender roles typically says that men and women have different gender roles as determined by natural law. Such views may be seen as more ‘traditional’ than the views of modern (secular) society, but there is a range of views within both camps. The syllabus mentions two texts in particular regarding Christian teaching on gender roles: Ephesians 5:22-33 and Mulieris Dignitatem.

Christian teaching on gender roles typically says that men and women have different gender roles as determined by natural law. Such views may be seen as more ‘traditional’ than the views of modern (secular) society, but there is a range of views within both camps. The syllabus mentions two texts in particular regarding Christian teaching on gender roles: Ephesians 5:22-33 and Mulieris Dignitatem.

Ephesians 5:22-33

| Verses supporting a traditional interpretation of gender roles | Verses supporting a more modern interpretation of gender roles |

| “Wives, submit yourselves to your own husbands as you do to the Lord.” (verse 22) | “Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her”. (verse 25) |

| “For the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the church” (verse 23) | “husbands ought to love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself.” (verse 28) |

| “Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit to their husbands in everything.” (verse 24) | “a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.” (verse 31) |

On the one hand, the verses suggesting that the husband is above – “the head of” – the wife, and that “wives should submit to their husbands in everything” support a traditional view of gender.

On the other hand, the next few verses command men to love, care, sacrifice, and potentially die for their wives as Jesus did for humanity. Rather than seeing wives as less important, husbands are told they “ought to love their wives as their own bodies“. The idea that man and woman become “one flesh” in marriage suggests a sense of equality – they are a single unit and so neither is above the other. This idea of husband and wife being “one flesh” comes from Genesis 2:24 and is discussed in Mulieris Dignitatem.

Mulieris Dignitatem

Mulieris Dignitatem – Latin for ‘the Dignity of a Woman’ – is a letter written by Pope John Paul II in 1988 in response to issues raised by the rise of (second-wave) feminism. In this letter, Pope John Paul II provides scriptural justification for equality between men and women:

- Genesis/creation story: God created humanity – male and female, Adam and Eve – in His image (Genesis 1:27), so both genders are equally human and equally made in God’s image. In marriage, husband and wife are “one flesh” (Genesis 2:24). Although Eve is created as ‘help’ for Adam (Genesis 2:18), the full context reveals that it is an equal relationship where “in his turn he must help her”. It is only after the Fall that God tells Eve that “Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you” (Genesis 3:16, emphasis added). So, rather than God willing men to rule over women, this inequality represents a disturbance to the fundamental equality of men and women intended by God. This disturbance is a consequence of man’s sinful post-fall nature.

- New Testament/Jesus’ example: Jesus’ treatment of women was at odds with the attitudes of his day. Rather than upholding “that tradition which discriminated against women”, the letter cites several examples where Jesus treats women with a dignity that was radical for the time (e.g. his healing of the woman with a flow of blood in Mark 5 described above or how Jesus told men that “prostitutes are entering the kingdom of God before you”). Jesus’ approach to women was so radical that even his disciples “marvelled” how he talked with a woman (John 4:27). The letter also highlights the importance of Mary as mother of Jesus, how women were the first to discover Jesus’ empty tomb, and how Jesus first appeared to Mary Magdalene after the resurrection (John 20:14), making her “the apostle of the Apostles”.

However, the letter also makes points that uphold a more traditional view of gender roles:

- It confirms the doctrine that only men can be priests.

- It confirms traditional gender roles, arguing that men and women are fundamentally different. It acknowledges women’s “rightful opposition” to Genesis 3:16 above, but argues that if women appropriate masculine characteristics as a response they will not “reach fulfilment” as women have an “image and likeness of God” that is specifically theirs and is different to that of men. However, the letter emphasises that no gender is better than the other, “they are merely different”.

- It emphasises the woman’s unique role and “psycho-physical structure” as mother (see below).

Christian vs. secular views of gender roles

Modern (Western) society is essentially secular and often takes a different view to Christianity on the issues of motherhood and different types of family. There are clearly a broad range of views within each camp, but the following examples contrast different views on these issues. Essay questions may ask you to consider which view is more accurate and whether Christian teaching should conform to secular views or resist them – see the AO2 evaluation points for more.

Motherhood

Christian teaching on gender typically sees motherhood as a key and defining feature of the female gender role. For example, Mulieris Dignitatem describes how:

- “the very physical constitution of women is naturally disposed to motherhood”.

- although parenting is a shared responsibility between man and woman, parenthood “is realized much more fully in the woman” due to the fact that she carries the baby inside her during the prenatal period, “which literally absorbs the energies of her body and soul”.

- The fact that the father is “outside the process of pregnancy and the baby’s birth” like this, means he must in some sense learn fatherhood from the mother’s example. “The “woman”, as mother and first teacher of the human being… has a specific precedence over the man”.

There is a wide range of secular views on motherhood and gender but secular feminist approaches typically reject motherhood as an essential part of womanhood. For example, in The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir argues that:

- “One is not born, but rather becomes a woman”. In other words, there is no essential – i.e. biological – female nature.

- Instead, women are socially conditioned into gender roles – which includes wanting to become mothers – as a result of social norms created by men.

- Raising children means women have to give up their own desires, interests, and careers.

Different types of family

Like with gender, Christian teaching on family is generally traditional – seeing children raised by a married heterosexual mother and father as the normative ideal. But again there is a range of views on a wide range of issues:

- Monogamy: Christian teaching typically forbids polygamy. For example, the Roman Catholic Church and Church of England only recognise marriages between one man and one woman. However, in the Old Testament, many figures – such as Abraham, Jacob, and David – had multiple wives.

- Homosexuality: Most Christian denominations do not recognise same-sex marriage. However, some denominations – such as the Episcopal Church – take a more liberal approach to homosexuality and bless same-sex marriages. Homosexual couples cannot naturally produce children, but this still leaves questions regarding adoption or artificial ways of producing children.

- Adoption: Christian teaching is generally in favour of adoption. For example, the story of Moses in Exodus. However, this is mostly only in the context of adoption into a heterosexual married family – Catholicism, for example, does not approve of homosexual couples adopting children.

- Abortion: On the issue of abortion, Christianity generally forbids abortion except in extreme cases (e.g. to save the mother’s life).

- Contraception: Views regarding family planning via contraception are more mixed – e.g. Catholicism forbids contraception but Protestant traditions usually don’t.

- IVF, gene-editing, etc.: Again, there are a range of technologies and a range of views here. Regarding in vitro fertilization (IVF), the Church of England permits it for (married heterosexual) couples struggling to conceive – but raises ethical and spiritual considerations. Catholic catechism #2377, however, describes IVF and similar techniques as “morally unacceptable” because “they dissociate the sexual act from the procreative act”.

Although there is no single secular view on different types of family, Western societies (i.e. UK, US, etc.) have moved away from legally upholding the traditional Christian view. For example, in the UK:

- Marriage: The law was changed in 2005 to allow civil partnerships between same-sex couples and in 2014 this was extended to full marriage rights. However, polygamous marriage is still not legally recognised as of 2024.

- Adoption: The Adoption and Children Act 2002 gave homosexual couples the right to adopt children.

- Abortion: Although technically still illegal, The Abortion Act 1967 made it effectively legal for women to get an abortion up to 24 weeks of gestation. Feminists typically – though not universally – see abortion rights as a key part of women’s rights.

- Contraception: Secular feminism aaaa.

AO2 evaluation: Christian vs. secular views on gender |

|---|

Issues for Christian vs. secular views on gender:

|

Gender and theology

Historically, Christianity can be seen as patriarchal – i.e. male dominated. For example, God in the Old Testament is referred to using male pronouns, Jesus was a man and chose all-male disciples, and even today many Christian denominations forbid women from occupying leadership roles. However, feminist theologians challenge this patriarchal interpretation of Christianity. The syllabus mentions comparisons between two feminist theologians in particular: Rosemary Radford Ruether and Mary Daly.

Rosemary Radford Ruether

Rosemary Radford Ruether was a Catholic feminist theologian. She argues that Christianity is not inherently sexist, but has been made that way over time by men and male leaders. As such, she argues Christianity should be reinterpreted to become compatible with feminism.

Jesus’ challenge to the male-warrior messiah expectation

Ruether contrasts the assumed (male) expectation of the messiah – based on Old Testament prophecy – with the reality of Jesus.

The expectation was that the messiah would be a military leader – like David in the Old Testament – who would liberate the Jewish people and restore Israel. The expectation was of a conquering and powerful king who would restore the kingdom of God by force.

However, Ruether argues that, historically, Christianity went wrong in trying to fit Jesus into this (masculine) Davidic military leader role – that this view isn’t accurate. If we discard this expectation and focus on what Jesus actually did, his teachings and example often invoke what are typically considered to be feminine qualities:

- Jesus used words, rather than violence.

- Rather than dominating and ruling over others, he served them.

- Jesus referred to God as Abba/father – implying a familial relationship – rather than the traditional hierarchical/dominant-subordinate “God-language”.

Ruether argues that Jesus could have come to earth as either a man or a woman – that his gender wasn’t important.

God as the female wisdom principle

In ancient Greek mythology, wisdom was personified in female form, Sophia. And this language is also found throughout the Old Testament. For example, aaa Paul fake wisdom of men aaa Wisdom of Solomon

Mary Daly

Mary Daly was a radical feminist theologian who was once a practising Catholic but disavowed Christianity.

Whereas Ruether sought to reform Christian theology from within – by reclaiming the female aspects of God and reinterpreting Scripture – Daly believed Christianity was beyond redemption and that women must move beyond traditional religion to reconnect with a more ancient, nature-based spirituality.

Christianity’s ‘Unholy Trinity’

Daly described Christianity as being shaped by an “unholy trinity” of rape, genocide, and war. These represent, for her, the violent and oppressive structures of patriarchal society, which she saw reflected in Christian theology, liturgy, and institutions. In her view, this violence is not incidental but fundamental to the way the Christian tradition has developed – especially through its use of male power and imagery.

Spirituality experienced through nature

aaa

AO2 evaluation: Christian feminist theology |

|---|

Issues for Christian feminist theology:

|

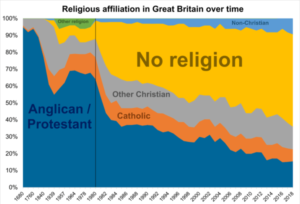

The challenge of secularism

Secularism is the view that religion should be separate from the state and public institutions – that government etc. should be neutral with regards to religion. The trend in UK society is towards increasing secularisation.

Secularism is the view that religion should be separate from the state and public institutions – that government etc. should be neutral with regards to religion. The trend in UK society is towards increasing secularisation.

This topic considers whether increasing secularisation is a good or bad thing, including:

- The view of Freud and Dawkins that God is an illusion and belief in God is bad for society

- The secular humanist view that Christianity is a personal belief should not be part of public life

The view that God is an illusion and Christianity is bad for society

Atheists Sigmund Freud and Richard Dawkins see the Christian belief in God as an illusion. They also argue that this belief in God is bad for society.

Freud’s view of religion and its effects on society

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud explained religious belief in psychological terms. He saw belief in God as wish fulfilment and an illusion created by the mind in response to unpleasant feelings and psychological conflicts. For example:

- As children, our parents provide us safety and security. As adults, we still desire this, so create the idea of God to provide this sense of security.

- Belief in God and God’s forgiveness alleviates feelings of guilt.

- Belief in God alleviates feelings of purposelessness and helps people cope with a life that has no meaning.

- There is a lot of overlap with religious belief and the Oedipus complex that occurs in the phallic stage of sexual development (see the religion and ethics page for more). During this stage, boys become jealous of their fathers. They end up repressing this jealousy into their subconscious, but these repressed feelings are projected in adult life onto the made up idea of God – the ultimate father figure. Freud’s equivalent explanation of religious belief in girls/women isn’t really developed.

Freud saw religious belief as a major cause of neurosis (a broad term for mental disorders that have symptoms similar to anxiety and stress) due to the way it represses and shames natural human instincts.

Freud also argued that, during the early stages of human civilisation, religion played a positive role in keeping people in line. For example, telling people that God forbids and will punish murder prevented “the great mass of the uneducated and oppressed” from killing people. However, Freud hoped that modern civilisation could move beyond this and replace faith in God with reason.

Dawkins’ view of religion and its effects on society

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins argues that religious belief is false. Things we once explained with God (e.g. the existence of human beings) eventually get explained with science (e.g. evolution). He argues that we should form beliefs on the basis of evidence and reason and that the evidence for belief in God is weak. Most of the reasons for religious belief – e.g. tradition, authority, revelation – are bad, he says.

Further, Dawkins argues that religious belief has several negative effects on society, such as:

- Discourages scientific progress: E.g. Dawkins complains about how faith schools might teach creationism rather than evolution, or that God created the world in 7 days 6,000 years ago rather than the big bang theory.

- Causes wars: E.g. the Crusades and conflicts in the Middle East.

- Indoctrinates children: E.g. Dawkins argues children should be taught to think for themselves rather than labelled as ‘Christian’ (or ‘Muslim’, ‘Jewish’, etc.) when they are too young to decide.

The view that Christianity should not be part of public life

Secular humanism is the view that humans can live good and moral lives without religion. The 2002 Amsterdam Declaration by Humanists International lists core humanist values including:

- Ethics

- Rationality

- Human rights

- Personal liberty

- Social responsibility

Secular humanists argue that society can thrive and flourish based on human, rather than specifically spiritual, values. Most secular humanists would argue that religious belief is personal and should not be part of public life. As such, they typically oppose faith schools and argue for separation of church and state.

Government and State

Unlike e.g. France or the USA, England is technically (de jure) a Christian country: the Anglican Church is the official state religion. However, in practice (de facto), most people in modern Britain are not Christian, and the Church of England has little influence on the state.

Even so, there are still historical links between Church and State. For example, some bishops (known as Lords Spiritual) automatically get seats in the House of Lords. Further, each sitting of parliament begins with a Christian prayer¹.

Education and schools

Around 1/3 of state-funded schools in the UK are faith schools¹, i.e. schools that identify with and to some extent teach a particular religion. Of these 1/3 of schools, the vast majority are Christian (Church of England or Catholic).

AO2 evaluation: The challenge of secularism |

|---|

Issues relating to the challenge of secularism:

|

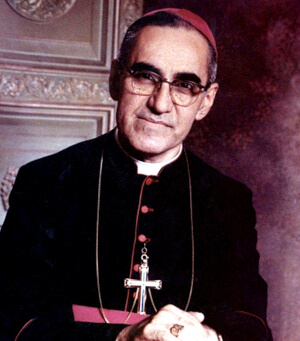

Liberation theology and Marx

Marxism is an economic and political theory that emphasises social justice and liberation of the poor and oppressed. And liberation theology is a Christian movement that overlaps with many of these same themes. This topic looks at the links between these two movements and considers the legitimacy of liberation theology as an expression of Christianity.

Marxism

Marxism is a social, political, and economic theory developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels which says:

- Society is divided into classes, with the working class (proletariat) oppressed and exploited by the ruling class (bourgeoisie).

- This oppression and exploitation is an inevitable result of capitalism.

- Capitalism dehumanises proletariat workers and treats them as a means to an end, leading to alienation:

- Alienated from the product they make: Someone else (bourgeoisie) has designed the product the worker makes.

- Alienated from the act of production: Workers have no control over how they make the product (e.g. they work on production lines doing repetitive and monotonous tasks).

- Alienated from their own potential: Workers have to work to survive, which leaves little time or energy to pursue other activities that could enrich their lives.