<<< Back to philosopher profiles

Aristotle

- Born: 384 BC (Stagira, Greece)

- Died: 322 BC (Euboea, Greece)

Biography

Biography

Aristotle was born in 384 BC in Stagira, northern Greece. His father, Nicomachus, was physician to the Macedonian king, which introduced Aristotle to medicine and biology at an early age. At age 17, Aristotle travelled to Athens to study at Plato’s Academy, where he remained for nearly 20 years.

Though Plato was a significant influence on Aristotle, he often diverged from Plato’s ideas – especially regarding the nature of reality and the forms. After Plato’s death, Aristotle left Athens and spent time travelling and studying natural phenomena. In around 343 BC, Aristotle began tutoring a young Alexander the Great at the request of his father, King Philip II of Macedon. In 335 BC, Aristotle returned to Athens to establish his own school, the Lyceum. The Lyceum’s structure was novel for its time; Aristotle’s method involved not only philosophical discussion but also empirical research, particularly in the natural sciences. Aristotle continued to teach in Athens until 323 BC until political unrest led him to leave for Euboea.

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle’s works are foundational to Western philosophy – representing an alternative, empirical, approach. In addition to philosophy, Aristotle’s work had a lasting impact on science. His ideas on biology, physics, and causation influenced scientific inquiry for centuries, shaping both medieval scholarship and early modern science, including figures like Galileo and Darwin who would build on and revise his foundational concepts.

Key Ideas

Virtue Ethics

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle pioneered a practical, character-based, approach to moral philosophy known as virtue ethics. Rather than focusing on rules or consequences – on which actions are good and bad – Aristotle’s approach to ethics emphasises being a good person.

The starting point of Aristotle’s ethics is eudaimonia. Modern translations of this term include simply ‘happiness’, but this is a bit misleading as eudaimonia is more than just a temporary psychological or emotional state. Other translations include ‘human flourishing’ or ‘living and fairing well’ – it means a good life in a broad sense. To achieve eudaimonia, a person must cultivate virtues – character traits that dispose them towards acting correctly. According to Aristotle, virtues are the ‘mean’ between two extremes. For example, courage is a virtue that lies between recklessness (a vice of excess) and cowardice (a vice of deficiency). In the same way that eating healthily, for example, is a habit that develops over time, so too are virtues developed through habit: if you continuously decide to act courageously when the opportunity arises it eventually becomes your natural reaction – part of your character. Developing virtuous character ensures a person will act in the right way and, over a lifetime, will achieve eudaimonia.

So Aristotle’s virtue ethics is the other way round to many other ethical approaches: Rather than saying a good person is one who does good actions, Aristotle says good actions are those done by good – or virtuous – people.

Metaphysics and Epistemology

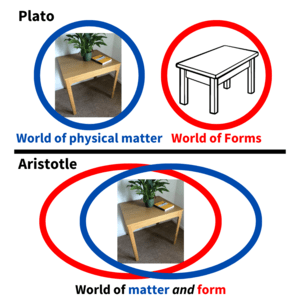

Aristotle’s understanding of reality and how we acquire knowledge of it diverges significantly from his teacher, Plato. Where Plato saw reality as divided into two separate realms – appearances and Forms – Aristotle argued that forms are not separate but instead exist within individual substances. Every substance is a combination of form (what a thing is) and matter (what it is made of).

Aristotle’s understanding of reality and how we acquire knowledge of it diverges significantly from his teacher, Plato. Where Plato saw reality as divided into two separate realms – appearances and Forms – Aristotle argued that forms are not separate but instead exist within individual substances. Every substance is a combination of form (what a thing is) and matter (what it is made of).

To explain the existence and changes in things, Aristotle introduced the 4 causes:

- The material cause (what something is made from),

- E.g. the material cause of a table might be the wood it’s made from.

- The formal cause (its shape or design),

- E.g. the formal cause of a table would be its flat surface and four legs.

- The efficient cause (the process or agent that brings it about),

- E.g. the carpenter who carved the table from wood might be the efficient cause of a table.

- And the final cause (its purpose or function).

- E.g. the purpose of a table is to be a platform on which people write, eat, etc. so this is its final cause.

Aristotle believed that all human knowledge begins with sensory experience. Unlike Plato, who argued that knowledge of the forms is innate and accessed through reason (a rationalist approach), Aristotle contended that we gain knowledge through observing the natural world (empiricism). He argued that the mind processes information from the senses and abstracts general principles from particular experiences. This emphasis on empirical observation laid the groundwork for the scientific method.

Logic and the Organon

Aristotle is often credited as the ‘father of logic’ because he was the first to develop a formal system for reasoning (outlined in a series of texts later called the Organon).

Aristotle’s logical system is centred on syllogistic reasoning – a method for drawing conclusions from premises. A syllogism consists of two premises followed by a conclusion, structured in a way that, if the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. For example:

- Premise 1: All humans are mortal.

- Premise 2: Socrates is a human.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Aristotle categorised syllogisms into different forms and established rules for determining whether a syllogism was valid. This system enabled philosophers to assess the correctness of arguments and helped build a systematic approach to knowledge.

Aristotle also introduced the laws of thought, which are foundational principles that guide logical reasoning. These include the Law of Non-Contradiction (something cannot be both true and false at the same time in the same respect) and the Law of the Excluded Middle (a statement must either be true or false, with no middle option). These principles form the basis of classical logic.

Aristotle’s contributions to logic laid the foundation for deductive reasoning and remained the standard in Western thought for over two millennia. Through the Organon, Aristotle provided tools for scientific inquiry, reasoning, and debate. His logical methods shaped medieval scholasticism and influenced the development of modern formal logic, demonstrating his profound and lasting impact on the field.

Political Theory and the State

Aristotle viewed human beings as naturally social and argued that the state exists to help people achieve a good life. In Politics, he defined humans as ‘political animals,’ meaning they flourish best within a community.

Aristotle analysed different types of government (monarchy, aristocracy, and polity) and their corrupt forms (tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy), proposing that a mixed constitution (a combination of elements) was most stable. He also emphasised that good political systems promote justice, education, and the welfare of all citizens.

Aristotle’s political theory, particularly his emphasis on civic engagement and the idea of the ‘common good,’ has had lasting influence on Western political philosophy and the development of democratic thought.

Quotes

“What is the good for man? It must be the ultimate end or object of human life: something that is in itself completely satisfying. [Eudaimonia] fits this description.”

– Nicomachean Ethics

“The man who shuns and fears everything and stands up to nothing becomes a coward; the man who is afraid of nothing at all, but marches up to every danger, becomes foolhardy. Similarly the man who indulges in every pleasure and refrains from none becomes licentious; but if a man behaves like a boor and turns his back on every pleasure, he is a case of insensibility. Thus temperance and courage are destroyed by excess and deficiency and preserved by the mean.”

– Nicomachean Ethics

“One swallow does not make a summer; neither does one day. Similarly neither can one day, or a brief space of time, make a man blessed and happy.”

– Nicomachean Ethics

“Hence it is evident that a city is a natural production, and that man is naturally a political animal.”

– Politics

Influences and Influenced

Influences: Aristotle was influenced by a range of thinkers, notably Plato, who provided a foundation in metaphysics and ethics which Aristotle then responded to. Aristotle also drew on the pre-Socratic philosophers’ focus on explaining the natural world and was influenced by Hippocrates’ approach to understanding life scientifically. Aristotle’s own empirical focus was partly inspired by his early experiences observing and studying natural phenomena.

Influenced: Aristotle’s work laid the foundation for a wide array of fields, from metaphysics to biology. His ideas profoundly shaped medieval philosophers, such as Thomas Aquinas, who integrated Aristotle’s ideas into Christian theology. In the Renaissance, Aristotle’s views were revived, influencing the development of modern science and political philosophy. Thinkers from Immanuel Kant to Alasdair MacIntyre have engaged with and expanded upon Aristotle’s ethics, while his scientific approach laid groundwork for figures like Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton.

Key Works and Further Reading

- Nicomachean Ethics

- Politics

- Metaphysics

- Physics

- Poetics

- On the Soul