<<< Back to philosopher profiles

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

- Born: July 1, 1646 (Leipzig, Holy Roman Empire)

- Died: November 14, 1716 (Hanover, Holy Roman Empire)

Biography

Biography

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was born in Leipzig in 1646. A precocious child, he began reading Latin by age seven and quickly taught himself Greek. By 15, he was studying philosophy and law at the University of Leipzig, where he became fascinated by logic, mathematics, and metaphysics.

Leibniz’s career was diverse: he worked as a diplomat, historian, librarian, and advisor to various European rulers. Despite his many political and administrative duties, he devoted much of his time to philosophy and mathematics, leading to groundbreaking contributions in both fields. He independently developed calculus, a discovery that led to a bitter dispute with Isaac Newton over priority.

Leibniz was not content to focus on one discipline. He envisioned a universal science, a grand intellectual system that would unify all knowledge. His vast body of work includes theories on metaphysics, logic, theology, and epistemology, and he engaged with many of the great thinkers of his time, including Spinoza, Malebranche, and Locke. Despite his intellectual achievements, Leibniz was largely ignored by his contemporaries while alive and died in relative obscurity in 1716.

Key Ideas

Monadology

One of Leibniz’s most famous contributions to philosophy is his Monadology (1714), in which he presents a radically unique vision of reality. According to Leibniz, the universe is composed of monads: simple, indivisible substances that contain their own internal principles of action.

Monads are not physical atoms but rather metaphysical entities that do not interact causally with one another. Instead, they exist in a state of pre-established harmony, orchestrated by God. Each monad reflects the entire universe from its own unique perspective, much like individual mirrors reflecting the same scene from different angles.

Leibniz’s monads are hierarchical: at the lowest level are the simplest monads, which constitute physical objects; at higher levels are monads capable of perception and consciousness; and at the highest level is God, the supreme monad who ensures the harmony of all others.

Truths of Reason vs. Truths of Fact

Leibniz distinguished between two fundamental kinds of truth:

- Truths of Reason: Necessary truths that are true in all possible worlds. These include mathematical and logical statements, such as “2 + 2 = 4” or “All bachelors are unmarried.” Their negation leads to a contradiction, meaning they cannot be false.

- Truths of Fact: Contingent truths that depend on how the world happens to be. These include historical or empirical statements, such as “Napoleon lost at Waterloo.” Their negation does not involve a contradiction, meaning they could have been otherwise.

For Leibniz, truths of fact ultimately rest on the principle of sufficient reason, which states that everything must have an explanation, even if we do not always know it. This principle plays a crucial role in Leibniz’s cosmological argument for the existence of God.

Innate Knowledge

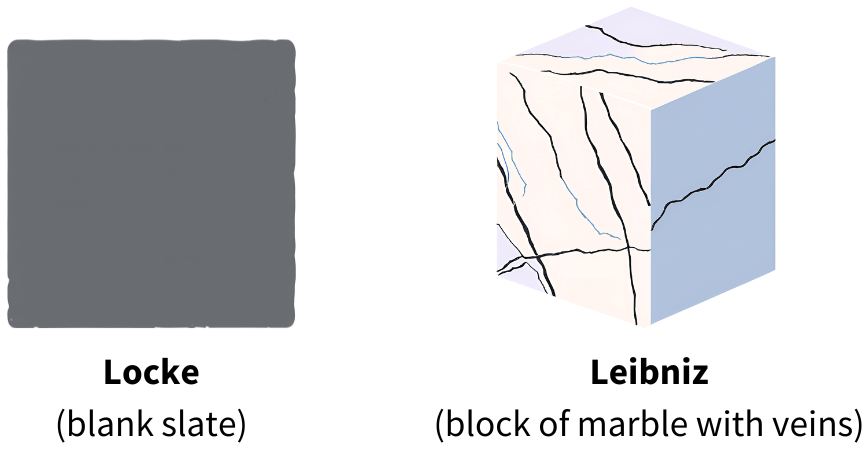

Leibniz was one of the most vocal critics of John Locke’s empiricism, particularly Locke’s rejection of innate ideas. Locke argued that the mind is a tabula rasa – a blank slate at birth, with all knowledge coming from experience. Leibniz strongly disagreed, defending the rationalist position that some knowledge must be innate and present in the mind prior to experience.

Leibniz’s response to Locke came in New Essays on Human Understanding (1704), a book structured as a direct critique of Locke’s work. Where Locke described the mind at birth as a blank slate, Leibniz compared the mind to veined marble – a rock containing shapes that are uncovered by a sculptor.

In other words, while experience helps shape and develop knowledge, the structure of the mind already contains predispositions that guide how we process and form ideas. For Leibniz, certain fundamental truths – such as logic, mathematics, and moral principles – cannot come from experience alone, because experience only provides particular instances, whereas these truths are universal and necessary.

Leibniz’s critique of Locke became one of the defining debates between rationalism and empiricism, shaping later philosophical discussions on epistemology and cognitive science. The dispute anticipated Kant’s later synthesis, where he argued that knowledge arises from the interaction between innate structures of the mind and experience.

Best of All Possible Worlds Theodicy

Leibniz’s theodicy – his response to the problem of evil – is to argue that we live in “the best of all possible worlds”. Leibniz believed that, given God’s omnipotence, omniscience, and omnibenevolence, God would only create a world that balances the greatest amount of good with the least amount of evil.

This does not mean the world is perfect – Leibniz acknowledged the presence of suffering and imperfection – but rather that any other possible world would have been worse in some way. God, in His infinite wisdom, chose the best possible arrangement of reality.

Calculus and the Dispute with Newton

One of Leibniz’s most famous achievements outside philosophy was his independent development of calculus. His notation (e.g., ∫ for integrals and d for differentials) remains the standard in modern mathematics. However, his claim to priority in discovering calculus led to a major dispute with Isaac Newton, whose followers accused Leibniz of plagiarism.

The Leibniz-Newton controversy became one of the most infamous intellectual feuds in history. Newton’s supporters, including the Royal Society, insisted that Newton had discovered calculus first, while Leibniz’s defenders pointed out that his notation and methods were entirely original. Modern historians generally agree that both men developed calculus independently, though Newton’s approach was more geometric and Leibniz’s more symbolic and algebraic.

Quotes

“There are also two kinds of truths: truth of reasoning and truths of fact. Truths of reasoning are necessary and their opposite is impossible; those of fact are contingent and their opposite is possible.”

– Monadology

“no fact can ever be true or existent, no statement correct, unless there is a sufficient reason why things are as they are and not otherwise – even if in most cases we can’t know what the reason is.”

– Monadology

“necessary truths are innate, are proved by what lies within, and can’t be established by experience in the way truths of fact can.”

– New Essays on Human Understanding

“And this design of the best being of such a nature that the good must be enhanced therein, as light is enhanced by shade, by some evil which is incomparably less than this good, God could not have excluded this evil, nor introduced certain goods that were excluded from this plan, without wronging his supreme perfection. So for that reason one must say that he permitted the sins of others, because otherwise he would have himself performed an action worse than all the sin of creatures.”

– Theodicy

“It is true that one may imagine possible worlds without sin and without unhappiness, and one could make some like Utopian or Sevarambian romances: but these same worlds again would be very inferior to ours in goodness.”

– Theodicy

Influences and Influenced

Influences: Leibniz was heavily influenced by Aristotle, Plato, and Scholastic thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus. He also engaged critically with Descartes, Spinoza, and Hobbes, developing his own rationalist system in response.

Influenced: Leibniz’s ideas on metaphysics, logic, and calculus had a profound impact on later thinkers. Immanuel Kant grappled with Leibniz’s rationalism in developing his own philosophy. His work in logic anticipated the formal logic of Frege, Russell, and Gödel, while his vision of a universal symbolic system foreshadowed modern computer science.

Key Works and Further Reading

-

- Discourse on Metaphysics (1686)

- Theodicy (1710)

- Monadology (1714)

- New Essays on Human Understanding (published posthumously in 1765)