<<< Back to philosopher profiles

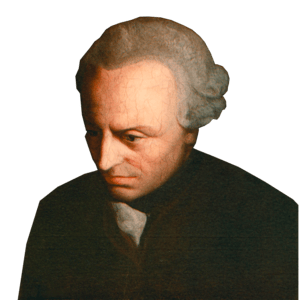

Immanuel Kant

- Born: April 22, 1724 (Königsberg, Prussia, now Kaliningrad, Russia)

- Died: February 12, 1804 (Königsberg, Prussia, now Kaliningrad, Russia)

Biography

Biography

Immanuel Kant was born in 1724 in Königsberg, a small city in Prussia, where he spent his entire life. Raised in a devoutly religious household, Kant was educated at the University of Königsberg, where he studied philosophy, mathematics, and natural sciences.

After many years working as a tutor to the children of wealthy families in the local area, Kant eventually became a professor at the University of Königsberg. He lived a highly disciplined life, keeping such a strict and consistent routine that locals would supposedly set their clocks by his daily walks.

Immanuel Kant published his major works later on in life, notably beginning with the Critique of Pure Reason at age 57. His ideas in epistemology and ethics, developed during an era of heated debate between rationalism and empiricism, have established him as one of the key figures in Western thought.

Key Ideas

Transcendental Idealism

Kant’s theory of Transcendental Idealism is mainly outlined in Critique of Pure Reason (1781). He argued that we don’t experience the world exactly as it is, but instead see a version shaped by our minds. Kant distinguishes between:

- The phenomenal world: The world as it appears to us

- The noumenal world: The world as it exists independently.

Kant’s idea here is that our minds actively shape reality, so what we know is a blend of the external world and our mental framework.

According to Kant, the mind has structures and categories that filter and organise everything we perceive. Ideas such as space and time are not features of the external world itself but are instead ways that the mind organises and interprets experience. Space and time, he argued, are forms of intuition that shape how we perceive things, rather than actual properties of objects in the world. This means that we never experience objects ‘as they are’ independently of us (the noumenal world) but always through these mental structures, resulting in the phenomenal world – the world as it appears to us.

This distinction between noumenal and phenomenal is crucial to Kant’s transcendental idealism: our knowledge is always shaped by these inherent mental structures, so we can never have direct access to things in themselves.

Synthetic A Priori Knowledge

In Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Kant argued for synthetic a priori knowledge – that is, knowledge of propositions that are not merely true by definition (synthetic propositions) that can be arrived at independently of any experience (a priori). This is in contrast to empiricists – in particular David Hume – who argued that synthetic propositions can only be known after experience (a posteriori).

This idea of synthetic a priori knowledge was crucial for Kant’s philosophy. He used it to argue that we can have certain and meaningful knowledge about the world that isn’t just based on observation. For example, Kant argued that mathematical truths like ‘7 + 5 = 12’ are not learned from experience but are universally true; they are also fundamental to how we understand the world. Kant saw this as proof that the mind has built-in structures for understanding, allowing us to have reliable knowledge that still relates to experience.

The Categorical Imperative

Kant’s Categorical Imperative, introduced in Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), is his central idea in ethics. It’s a rule that tells us how to decide if an action is morally right. Kant believed that moral actions must follow universal principles, which he explained through three main versions or ‘formulations’ of the Categorical Imperative:

- The Universal Law Formula: This says we should only act in ways that could apply as universal laws. For example, if everyone lied as a universal law – i.e. all the time – then nobody would believe anything anybody said, so it couldn’t be followed as a universal law. As such, lying is wrong according to the universal law formula. Kant’s point is that if a principle couldn’t work as a universal rule, it can’t be morally acceptable.

- The Humanity Formula: This version tells us to treat people as ends in themselves, not as means to an end. It means respecting each person’s own goals and autonomy. For example, if you steal money from somebody, you are using that person as a means to get money without regard for whether that person wants you to have their money – without regard to their ends. So, stealing is wrong according to the humanity formula. Kant’s point is that each person has moral value and that it is wrong to ignore this by using them selfishly for your own goals.

- The Kingdom of Ends Formula: Kant’s third version imagines an ideal society where everyone acts morally and respects each other. In this ‘kingdom of ends,’ people follow universal principles and treat others with respect. Kant’s idea here is that we should act as if we are contributing to a world where everyone upholds mutual dignity and fairness.

Quotes

“Without the sensuous faculty no object would be given to us, and without the understanding no object would be thought. Thoughts without content are void; intuitions without conceptions, blind.”

– Critique of Pure Reason

“That is to say, it is not limited by, but rather limits, sensibility, by giving the name of noumena to things, not considered as phenomena, but as things in themselves.”

– Critique of Pure Reason

“Being is evidently not a real predicate, that is, a conception of something which is added to the conception of some other thing.”

– Critique of Pure Reason

“Hence there is only one categorical imperative and it is this: Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

– Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals

“Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of another, always at the same time as an end and never simply as a means.”

– Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals

“An action done from duty has its moral worth, not in the purpose that is attained by it, but in the maxim according to which the action is determined.”

– Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals

“Two things fill the mind with ever-increasing wonder and awe: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”

– Critique of Practical Reason

Influences and Influenced

Influences: Immanuel Kant was influenced by Descartes, Leibniz, and, in particular, David Hume. Hume’s empiricism, especially his scepticism about cause and effect, awakened Kant from what he described as a “dogmatic slumber” and inspired Kant to develop his own theories in response. Kant’s transcendental idealism was also influenced by the rationalism of Descartes and Leibniz. Like Kant, Descartes was interested in a priori knowledge. Leibniz’s rationalism also shaped Kant’s thinking, particularly Leibniz’s belief in innate ideas and the principle of sufficient reason.

Influenced: Kant’s ideas shaped later philosophers like Hegel, who built on Kant’s ideas about human understanding but argued that knowledge could be unified rather than split into the two separate realms of noumenon and phenomenon, as Kant had suggested. Kant’s influence even extends to existentialists like Sartre, who drew on Kant’s thinking with regards to autonomy and responsibility.

Key Works and Further Reading

- Critique of Pure Reason (German: Kritik der reinen Vernunft) (1781)

- Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (German: Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten) (1785)

- Critique of Practical Reason (German: Kritik der praktischen Vernunft) (1788)

- The Metaphysics of Morals (German: Die Metaphysik der Sitten) (1797)