<<< Back to philosopher profiles

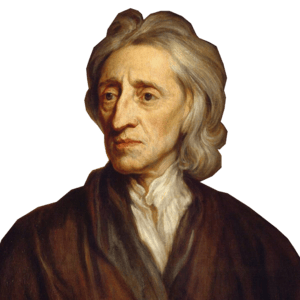

John Locke

- Born: 29 August 1632 (Wrington, Somerset, England)

- Died: 28 October 1704 (Essex, England)

Biography

Biography

John Locke was born in 1632 in Wrington, Somerset, and raised in a Puritan household. He studied at Christ Church, Oxford, where he was drawn to the ideas of modern philosophy and science. He later became a physician, though he never formally practised.

Locke fled to the Netherlands in 1683 due to political tensions, returning to England only after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which aligned with his ideas on constitutional government. Upon his return to England, Locke became a major intellectual force, contributing to debates on politics, epistemology, and education. He engaged with some of the most prominent thinkers of the time, including Isaac Newton. After a lengthy period of poor health, Locke died on 28 October 1704 and was buried in the churchyard of All Saints’ Church in High Laver.

Locke’s major work, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), laid the foundations for modern empiricism, arguing that the human mind at birth is a tabula rasa (blank slate) and that all knowledge comes from experience. His political philosophy, expressed in Two Treatises of Government (1689), strongly influenced liberal thought, advocating for natural rights and government by consent.

Key Ideas

Empiricism and the Mind as Tabula Rasa

Locke rejected the idea of innate knowledge, arguing instead that the human mind is born as a tabula rasa (blank slate), upon which experience writes. In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), he argued that all knowledge originates in experience and can be divided into two sources:

- Sensation: Knowledge gained from external sensory experience (e.g. colours and sounds).

- Reflection: Knowledge gained from internal mental operations (e.g. thinking and remembering).

Locke maintained that even complex ideas—such as justice, God, or morality—are ultimately built from these simple experiences, combined by the mind.

Locke’s empiricism brought him into direct conflict with the rationalist philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who defended the idea of innate knowledge. Locke argued that if ideas were truly innate, they would be universally present in all humans, including children and those unfamiliar with philosophy. Since such universal agreement did not exist, he concluded that all knowledge must come from experience.

Primary and Secondary Qualities

In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), Locke distinguishes between primary and secondary qualities of objects:

- Primary qualities: Inherent properties of an object that exist independently of perception. These are: size, shape, motion, and number.

- Secondary qualities: Properties that arise from the interaction between primary qualities and our senses, meaning they exist only in the mind. These include: colour, taste, smell, and feel.

For example, an apple’s roundness and size are primary qualities – they exist and are constant regardless of whether anyone perceives them. In contrast, the apple’s its redness and sweetness are secondary qualities produced by our perception – they are not inherent properties of the apple.

This distinction has been highly influential in the epistemology of perception. The distinction between mind-independent reality (primary qualities) and our perception of it (secondary qualities) can be seen as a precursor to indirect realism. George Berkeley also built on – and rejected – this distinction in arguing for idealism.

Personal Identity

Locke’s theory of personal identity, outlined in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), was groundbreaking in its emphasis on memory and psychological continuity.

Locke argued that personal identity – who we are – is not based on the persistence of a soul or substance (as earlier thinkers had suggested) but rather on the continuity of consciousness over time. According to Locke, a person remains the same individual as long as they remember their past experiences. This led to his famous thought experiment: If the soul of a prince were transferred into the body of a cobbler but retained the prince’s memories, Locke argued that the person should be considered the prince rather than the cobbler. This psychological criterion of identity raised complex questions about moral responsibility – if someone forgets committing a crime, are they still the same person who committed it? Locke acknowledged these difficulties but maintained that memory is the key to selfhood.

Natural Rights and Political Philosophy

John Locke’s political philosophy, particularly in his Two Treatises of Government (1689), laid the foundations for liberalism and the modern concept of natural rights. Locke argued that all individuals are born with inalienable rights – including life, liberty, and property – which exist independently of any government. He believed these rights were derived from natural law, a rational order established by God and discoverable through reason.

One of Locke’s most influential arguments concerns private property. In his theory, land and resources originally exist in a common state of nature, belonging to no individual. However, property becomes rightfully owned when a person mixes their labour with nature. For example, if someone cultivates a field, gathers fruit, or hunts an animal, their labour transforms the resource into personal property. However, Locke placed limits on this right, arguing that one should not take more than they can use and must leave enough for others.

Locke’s theory of government was based on the social contract, in which individuals voluntarily consent to political authority in exchange for the protection of their natural rights. However, he argued that government exists only as a trust – a conditional agreement between rulers and the people. If a government fails to uphold these rights or becomes tyrannical, the people not only have the right but the duty to overthrow it. This idea directly influenced the American Declaration of Independence and later revolutionary movements, as well as thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Thomas Jefferson.

Quotes

“Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas: How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the MATERIALS of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE.”

– An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

“For should the soul of a prince, carrying with it the consciousness of the prince’s past life, enter and inform the body of a cobbler, as soon as deserted by his own soul, every one sees he would be the same PERSON with the prince, accountable only for the prince’s actions.”

– An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

“Wherever law ends, tyranny begins.”

– Two Treatises of Government

“Being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.”

– Two Treatises of Government

Influences and Influenced

Influences: Locke’s empiricism was influenced by Aristotle’s emphasis on experience, as well as the scientific method developed by Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton. Locke admired Newton’s approach and sought to apply similar empirical reasoning to philosophy. He also responded to Descartes, particularly in his rejection of innate ideas and his insistence that all knowledge derives from experience. In political philosophy, Locke engaged with the ideas of Thomas Hobbes, though he rejected Hobbes’ authoritarianism, arguing instead for a government that exists to protect individual rights.

Influenced: Locke heavily influenced Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who disagreed with Locke on the innate knowledge. Locke’s empiricism also had a profound impact on later philosophers, particularly David Hume, who extended Locke’s ideas in a more radical direction, arguing that causation, the self, and external reality cannot be known with certainty – only inferred through experience. In political philosophy, Locke’s social contract theory heavily influenced the American and French revolutions, particularly Thomas Jefferson, who echoed Locke’s ideas in the Declaration of Independence. His work also shaped later liberal thinkers, such as John Stuart Mill, who developed Locke’s ideas on individual liberty and limited government into a more fully articulated theory of liberal democracy.

Key Works and Further Reading

- An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689)

- Two Treatises of Government (1689)

- A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689)

- Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693)