<<< Back to philosopher profiles

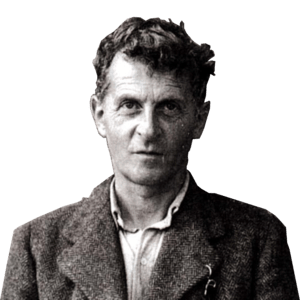

Ludwig Wittgenstein

- Born: April 26, 1889 (Vienna, Austria)

- Died: April 29, 1951 (Cambridge, England)

Biography

Biography

Ludwig Wittgenstein was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1889. His father, Karl Wittgenstein, was one of the richest men in Europe and a demanding figure with high expectations for his children. 3 of Ludwig’s brothers – Hans, Rudolf, and Kurt – died by suicide before age 30.

Wittgenstein initially studied aeronautical engineering at the University of Manchester but, while there, became interested in the philosophy of mathematics, which led him to study under Bertrand Russell at Cambridge University in 1911.

After the outbreak of World War I, Wittgenstein joined the Austro-Hungarian army in August 1914. It was during this time as a soldier that he wrote his first major philosophical work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. After the war, Wittgenstein gave away his inheritance, worked as a teacher in rural Austria, and later returned to Cambridge University in the 1920s to resume his philosophical work.

Wittgenstein’s later years were spent developing ideas that challenged his earlier work, resulting in his second major book, Philosophical Investigations. Despite publishing little during his lifetime, Wittgenstein’s ideas have become foundational in 20th-century philosophy.

Key Ideas

Wittgenstein’s ideas are often divided into his early and later philosophy because the two approaches are radically different and often directly contradictory.

Early Philosophy: Picture Theory of Language

In Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), Wittgenstein developed the “picture theory of language.” He argued that language represents the world by creating “pictures” of facts. A proposition is true if the state of affairs it depicts actually exists in the world; it is false if it does not.

A sentence, according to this view, works like a model or diagram, reflecting the logical structure of the reality it describes. For example, the sentence “The cat is on the mat” represents a specific arrangement of objects (a cat and a mat) in the world. If the cat is indeed on the mat, then “The cat is on the mat” is true. If the cat is not on the mat, the proposition is false. This proposition is meaningful because it depicts how things could be arranged.

For Wittgenstein, a meaningful proposition is one that can be shown to correspond to a possible state of affairs in the world. This idea was central to his belief that philosophy should clarify language and avoid metaphysical speculation.

Limits of Language

Wittgenstein’s early philosophy emphasised the limits of what can be meaningfully said. He famously concluded the Tractatus with the statement: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” This suggests that many philosophical problems arise from trying to discuss matters beyond the boundaries of language. Issues like ethics, aesthetics, and metaphysics – though important – are not things that can be articulated within the framework of logical language, according to Wittgenstein.

Later Philosophy: Meaning as Use

In his later work, Philosophical Investigations (1953, published posthumously), Wittgenstein radically revised his earlier ideas. Whereas the picture theory of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (see above) saw language as a fixed and rigid system of representation, Wittgenstein argued the meaning of words cannot be isolated from context in this way. Instead, he argued, the meaning of a word differs depending on how it is used.

Form of Life

A “form of life” is the shared social and cultural practices, activities, and ways of understanding that provide the context for language use. For Wittgenstein, the meaning of words and symbols cannot be separated from this – to understand language you have to understand the forms of life in which it is embedded.

Wittgenstein argued that the meanings of words and sentences derive from their role within specific forms of life, shaped by shared human behaviours and customs. For example, in the context of a religious form of life, the phrase “God is omnipotent” might express devotion and belief. But for a secular philosopher, however, the same statement might prompt a discussion about metaphysics or the limits of human language to describe divinity. Similarly, the word “checkmate” makes sense only in the form of life associated with playing chess. Outside of that game, it loses its meaning entirely or takes on metaphorical uses, such as describing a situation of inevitable defeat. Through these examples, Wittgenstein highlighted that our understanding of language is inseparable from the social and practical contexts in which it is used.

Philosophy, on this view, is not about constructing theories but about resolving confusions that arise from misusing language. Wittgenstein compared philosophy to therapy, aiming to untangle the knots created by linguistic misunderstandings.

Family Resemblance

Wittgenstein introduces the concept of family resemblance to explain how certain concepts or words do not have a single defining essence but are instead connected through overlapping similarities.

For example, Wittgenstein suggests the way terms like “game” function is akin to how members of a family share certain features: Different members may share the same eye colour, facial expressions, or mannerisms but there is no single feature they all have in common. Similarly, some games involve competition (like football), others involve luck (like roulette), and others involve neither (like playing ring-a-ring-a-roses). Despite this diversity, we still recognise all these activities as “games” due to a network of overlapping characteristics.

For example, Wittgenstein suggests the way terms like “game” function is akin to how members of a family share certain features: Different members may share the same eye colour, facial expressions, or mannerisms but there is no single feature they all have in common. Similarly, some games involve competition (like football), others involve luck (like roulette), and others involve neither (like playing ring-a-ring-a-roses). Despite this diversity, we still recognise all these activities as “games” due to a network of overlapping characteristics.

This idea of family resemblance challenges the traditional pursuit of absolute precision in philosophy. Wittgenstein would reject the notion that we need to provide the necessary and sufficient conditions or the Platonic Form that corresponds to words such as “beauty”, “knowledge”, or “justice” in order to understand what these words mean.

Private Language Argument

Wittgenstein argues that language is inherently public and that a private language would lack the communal context necessary to establish meaning.

To illustrate this, Wittgenstein uses the famous analogy of a beetle in a box. Imagine a society where each person has a box that only they can look into, and everyone calls the content of their box a “beetle.” Wittgenstein points out that, in such a society, it wouldn’t matter what was actually in anyone’s box because the word “beetle” derives its meaning not from the private contents of the boxes but from its use in the language. If everyone had something completely different in their box, or the object inside constantly changed, this wouldn’t change the meaning of the word “beetle” because no one can see in anyone else’s box anyway! And so, the meaning of “beetle” is entirely determined by what is public. The private stuff – what’s actually inside the box – is irrelevant to the meaning of “beetle.”

In this analogy, the box symbolises the mind, and the “beetle” represents a private sensation – mental states like “pain” or “happy”. This challenges traditional conceptions of the mind – in particular Cartesian dualism – which treat mental states as private inner objects only the subject has access to.

Quotes

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

– Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

“Philosophy is not a theory but an activity.”

– Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

“What can be shown cannot be said.”

– Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

“If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.”

– Philosophical Investigations

Influences and Influenced

Influences: Wittgenstein’s early ideas were influenced by the logical positivism of Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell, as well as by the broader traditions of analytic philosophy. His later work reflects a shift toward pragmatism and was shaped by his reflections on ordinary language and human practices.

Influenced: Wittgenstein’s ideas had a profound impact on a wide range of disciplines, including philosophy, linguistics, psychology, and anthropology. Philosophers like J.L. Austin and Gilbert Ryle were influenced by his emphasis on ordinary language, while his critique of private language shaped discussions in philosophy of mind.

Key Works and Further Reading

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921)

- Philosophical Investigations (1953, posthumous)

- On Certainty (1969, posthumous)

- The Blue and Brown Books (1958, posthumous)

- Culture and Value (1980, posthumous)