<<< Back to philosopher profiles

Plato

- Born: 428/427 or 424/423 BC (Athens, Greece)

- Died: 348 BC (Athens, Greece)

Biography

Biography

Plato was born in around 428 BC in Athens to a prominent and aristocratic family. His birth name was likely Aristocles, but he was given the nickname ‘Plato’, which translates to ‘broad’ or ‘wide.’ In his youth, Plato trained as a wrestler and pankrationist – the ancient equivalent of MMA.

He was initially drawn to politics, but his life changed after he met Socrates, whose dialectical style and philosophical inquiries deeply influenced him. Following Socrates’ execution, Plato left Athens to travel, studying under the Pythagoreans in Italy and engaging with various philosophical traditions. Around 387 BCE, he returned to Athens to establish the Academy, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world, where he taught and wrote until his death in 348 BCE.

Plato’s dialogues and teachings are foundational to Western philosophy and have influenced a wide range of subjects, from metaphysics to ethics to political theory.

Key Ideas

Theory of Forms

Central to Plato’s philosophy is the Theory of Forms, which says that the material world we experience is merely a shadow of a higher, unchanging, and perfect reality composed of abstract ideas or Forms.

For example, when you see a beautiful painting, you see a particular instance of beauty. However, this particular beautiful painting is merely an imperfect and incomplete reflection of a higher reality – the world of the Forms. According to Plato’s theory of Forms, pure beauty exists as a kind of perfect and eternal object and the painting – and all other beautiful things we experience – only reflect this Form in an incomplete way.

According to Plato, all things we experience participate in some Form or another. For example, if you were to draw a circle on a piece of paper, it would participate in the Form of the circle. However, that particular circle – however carefully you draw it – will never be perfectly round. Only the Form of the circle is perfect. There are many Forms, including the Form of the triangle, of justice, of man, of the number 3, and so on.

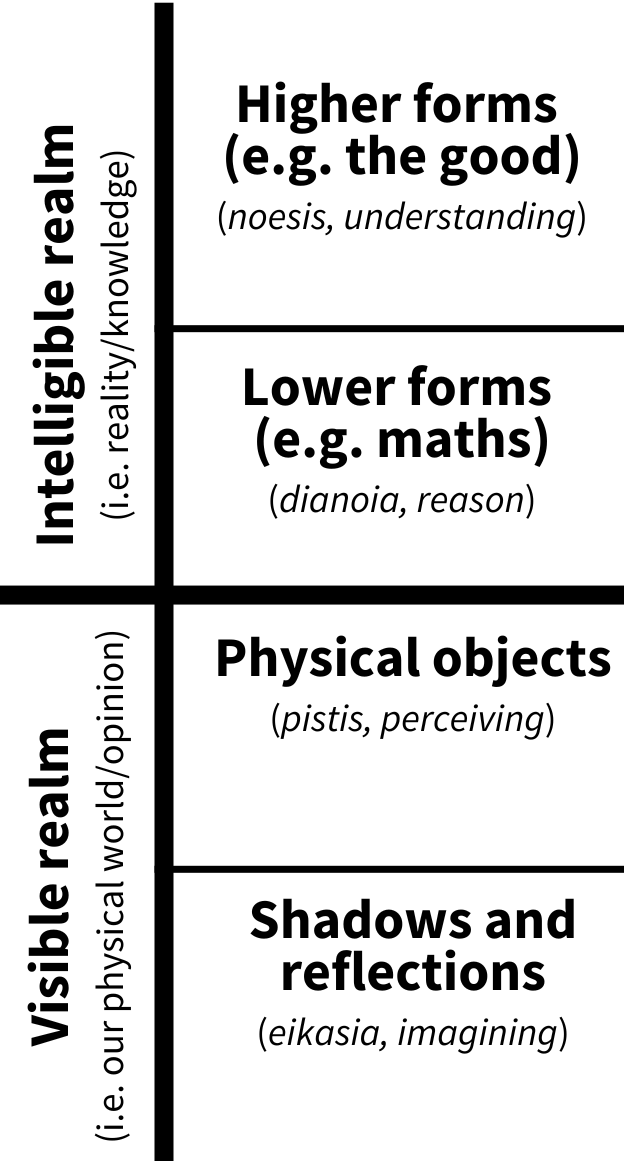

So Plato’s theory of Forms sees reality as divided into two realms: The temporary and imperfect world of appearances that we experience with our senses, and the eternal and perfect world of the Forms.

The Allegory of the Cave

Plato’s epistemology – his theory of knowledge – is related to his theory of Forms (above). Because the Forms cannot be experienced with the senses, and because these Forms are the true nature of reality, the senses can only give rise to opinion, not knowledge. Instead, for Plato, proper knowledge consists in the use of reason to understand the world of the Forms.

In The Republic, Plato presents his famous allegory of the cave to illustrate this difference between knowledge and opinion:

In The Republic, Plato presents his famous allegory of the cave to illustrate this difference between knowledge and opinion:

- Prisoners are chained facing a wall.

- Behind them, objects are paraded in front of a fire, casting shadows on to the wall.

- The prisoners think these shadows are reality because they never experience anything else.

- But one day, a prisoner escapes the cave and goes outside, seeing real objects and the sun that illuminates them.

- When the escaped prisoner returns to the cave and tells the prisoners the true nature of reality, they think he’s gone mad and don’t believe him.

The prisoners represent ordinary people, who take their sense perceptions of shadows on the wall to be knowledge of reality. The escaped prisoner, in contrast, represents the philosopher, who understands the truth and understands the shadows on the wall to be imperfect reflections of the true nature of reality.

The Soul

Just as Plato saw reality consisting of two parts – Forms and appearances – he also saw human beings as consisting of two parts:

- The temporary, changing, physical body,

- and the eternal, unchanging, soul.

Plato believed that the eternal soul originates in the world of the Forms (see above). Here, it possess true and perfect knowledge of reality. However, the soul gets drawn to the physical world by its appetites and desires and is born into a temporary physical body, which acts as a kind of prison for the soul. The body’s senses – such as sight and hearing – limit the soul’s access to true knowledge, offering only opinions based on appearances instead (see the allegory of the cave above). Through reason, however, we can remember truths the soul once knew in the world of the Forms. In the dialogue Meno, Plato intends to prove this by showing how a slave, through guided questioning, can recall geometric truths despite never having been taught them.

Plato’s idea of the soul is tripartite, consisting of reason, spirit, and appetite, each with distinct roles and functions. The soul’s purpose is to pursue truth and wisdom. When a person dies, the soul is freed from its bodily confinement and returns to the world of the Forms, resuming its natural state of eternal knowledge.

Justice and the Ideal State

The Republic outlines Plato’s vision of a just society, governed by philosopher kings who possess wisdom and virtue.

Plato defines justice as the harmonious arrangement of society’s three classes (rulers, warriors, and producers), mirroring the harmony that should exist within the individual’s soul (see above). According to Plato, justice in the individual and the state is achieved through the alignment of reason, spirit, and appetite, with reason guiding the other elements.

Quotes

“I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing.”

– The Republic

“The heaviest penalty for declining to rule is to be ruled by someone inferior to yourself.”

– The Republic

“The object of education is to teach us to love what is beautiful.”

– The Republic

“Have you ever sensed that our soul is immortal and never dies?”

– The Republic

Influences and Influenced

Influences: Plato was profoundly influenced by Socrates, whose dialectical method and ethical inquiries shaped Plato’s philosophical approach. Other significant influences included the teachings of Pythagoras, whose mathematical and metaphysical ideas contributed to Plato’s emphasis on abstract Forms and eternal truths. Plato was also influenced by earlier Greek thinkers like Parmenides and Heraclitus, whose ideas on change and permanence informed his metaphysical theories.

Influenced: Plato’s philosophy laid the groundwork for much of Western thought, directly shaping his student Aristotle, who developed his own approach in response to Plato’s ideas. The Neo-Platonists, including Plotinus, adapted and expanded his theory of Forms, impacting early Christian theology and thinkers like Augustine. During the Renaissance, Plato’s works were revived, inspiring philosophers such as Ficino and later Enlightenment thinkers. In modern philosophy, Plato’s ideas continue to resonate in metaphysics, ethics, and political theory.

Key Works and Further Reading