<<< Back to philosopher profiles

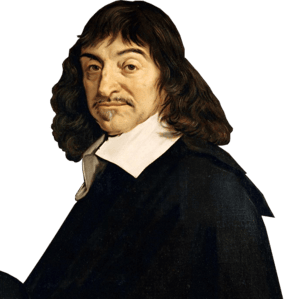

René Descartes

- Born: March 31, 1596 (La Haye en Touraine, France)

- Died: February 11, 1650 (Stockholm, Sweden)

Biography

Biography

René Descartes was born in 1596 in La Haye en Touraine, a small town in France. He studied law at the University of Orléans before joining the army of Maurice of Nassau in the Netherlands. As a young man, he travelled throughout Europe, engaging with the scientific and philosophical ideas of his time.

Often referred to as the father of modern philosophy, Descartes is known for his methodical approach to knowledge and reasoning, which he developed in works like Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) and Discourse on the Method (1637). He is perhaps most famous for his cogito argument: “I think, therefore I am.”

By his later years, Descartes was regarded as one of the top philosophers and scientists in Europe. He spent the later years of his life in Sweden, tutoring Queen Christina of Sweden, and died at the age of 53. Descartes’ approach and ideas revolutionised philosophy – in particular epistemology – by emphasising doubt and scepticism as tools for understanding certainty and knowledge.

Key Ideas

The Cartesian Method

In Discourse on the Method (1637), Descartes introduced his Cartesian method as a new approach to acquiring knowledge by eliminating doubt and building a secure foundation of certainty. He sought a method of inquiry that would reject unreliable beliefs, whether they came from the senses or traditional authorities, and instead follow a rigorous path toward truth.

The Cartesian method involves starts by doubting everything that can possibly be doubted. Descartes considers various reasons why his beliefs could be false – however unlikely they may seem. What you see could be an illusion, you could actually be in bed dreaming, or perhaps there is an extremely powerful evil demon that has been deceiving you your whole life. If there is any reason to doubt a belief, it is treated as false. Once everything that can possibly be doubted has been doubted, the Cartesian method uses reason to rebuild one’s beliefs and guarantee only the most certain and indubitable truths are taken as knowledge.

The method was influenced by his studies in mathematics, where clear rules and logical steps lead to reliable conclusions. Descartes proposed four main rules for guiding one’s thought:

- Accept only what is absolutely certain and clear: Descartes insisted that he would accept nothing as true unless it presented itself to his mind with such clarity and distinctness that he couldn’t doubt it. This rule was about avoiding hasty judgements and only accepting ideas that were absolutely certain.

- Divide complex problems into smaller parts: To understand difficult issues, Descartes recommended breaking them down into as many smaller, manageable parts as possible. This allowed him to resolve each part more effectively and avoid confusion.

- Go from simple to complex: Descartes suggested starting with the simplest and easiest-to-understand ideas and gradually working up to more complex knowledge. This approach aimed to build understanding in a logical and structured way, even when examining subjects without a clear order.

- Review thoroughly to ensure nothing is overlooked: Finally, Descartes emphasised the importance of reviewing and re-checking each step carefully to be certain that nothing had been omitted. This thoroughness ensured completeness and accuracy in his reasoning.

Cogito, Ergo Sum (I Think, Therefore I Am)

Descartes’ famous statement “cogito, ergo sum” comes from Discourse on the Method (1637) but is more closely associated with Meditations on First Philosophy (1641). Descartes’ point is that one’s own existence – “I am” – is a fundamental truth that cannot possibly be doubted.

Employing the Cartesian method described above, Descartes imagines a being with the power of a God who uses this power to deceive him – an evil demon. The possibility of this evil demon gives reason to doubt almost every belief because those same beliefs could be deceptions created by this evil demon and there would be no way to tell the difference. However, says Descartes, even if I am being deceived by this evil demon, I can’t doubt that I exist because there has to be something that exists for the evil demon to deceive in the first place! The very fact that you are able to doubt your own existence like this proves you do exist – thinking proves that you exist.

The thinking mind, according to Descartes, can be known with certainty. This serves as the foundation from which Descartes attempts to rebuild his knowledge.

Mind-Body Dualism

In Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), Descartes argued for mind-body dualism (also known as substance dualism or Cartesian dualism), the idea that the mind (or soul) and body are two distinct substances that can exist separately from one another.

For Descartes, the mind is a non-physical substance that thinks, reasons, and experiences; it is defined by consciousness and is independent of the physical world. The body, on the other hand, is purely physical and operates according to the laws of nature, like a machine. Descartes argued that mental and physical substances have completely different properties: The body is extended in space and subject to movement and mechanical processes, while the mind exists outside of space and has no physical form.

Descartes recognised that the interaction between mind and body required an explanation – if thoughts are non-physical, how can they interact with and move the physical body? In response to this question, Descartes proposed that the connection between them occurs in the pineal gland, a small part of the brain he believed was the “seat of the soul.”

Quotes

“If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things.”

– Principles of Philosophy

“It is not enough to possess a good mind; one must also apply it.”

– Discourse on the Method

“The first precept was never to accept a thing as true until I knew it as such without a single doubt.”

– Discourse on the Method

“I think, therefore I am.”

– Discourse on the Method

“I shall apply myself seriously and freely to the general destruction of all my former opinions… the slightest ground for doubt that I find in any, will suffice for me to reject all of them.”

– Meditations on First Philosophy

“I shall suppose, therefore, that there is, not a true God, who is the sovereign source of truth, but some evil demon, no less cunning and deceiving than powerful, who has used all his artifice to deceive me. I will suppose that the heavens, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds, and all external things that we see, are only illusions and deceptions which he uses to take me in.”

– Meditations on First Philosophy

“I understand that a chief difference between my Mind and Body consists in this, That my Body is of its Nature divisible, but my Mind indivisible… And this alone (if I had known it from no other Argument) is sufficient to inform me, that my mind is really distinct from my Body.”

– Meditations on First Philosophy

Influences and Influenced

Influences: René Descartes was influenced by Aristotle, St. Augustine, and Montaigne. Aristotle’s structured approach to knowledge inspired Descartes to seek clear, logical methods, although Descartes rejected much of Aristotle’s reliance on sense perception. Montaigne’s scepticism also influenced Descartes’ own radical doubt and his development of the Cartesian method. Augustine’s focus on self-awareness influenced Descartes’ cogito argument, as Augustine also argued that inner experience is a reliable foundation for knowledge. Descartes was also influenced by the cultural and intellectual climate of the day – especially the movement referred to as renaissance humanism. This movement emphasised individual reasoning rather than accepted authorities, and this likely inspired Descartes’ own philosophy based on reason and personal discovery.

Influenced: Descartes’ influence means he is often called the ‘father’ of modern philosophy. His ideas and approach to inquiry deeply influenced later philosophers like Spinoza, Leibniz, and Kant. His mind-body dualism influenced later debates in the philosophy of mind and psychology, and his emphasis on doubt and reason paved the way for Enlightenment thinkers like Locke and Hume.

Key Works and Further Reading

- Discourse on the Method (French: Discours de la méthode) (1637)

- Meditations on First Philosophy (Latin: Meditationes de prima philosophia) (1641)

- Principles of Philosophy (Latin: Principia philosophiae) (1644)

- The Passions of the Soul (French: Les passions de l’âme) (1649)