Substance dualism is the view that the mind is a completely different and distinct kind of substance to physical stuff.

In other words, it’s the view that the mind is entirely separate from the physical body and so could float off and exist completely independent of a physical body or a physical brain.

In other words, it’s the view that the mind is entirely separate from the physical body and so could float off and exist completely independent of a physical body or a physical brain.

Substance dualism is often called Cartesian dualism, after René Descartes. Descartes talks about the soul, rather than the mind, but the point of Cartesian or substance dualism is that there are two distinct realms:

- A physical realm (e.g. tables, chairs, your body)

- A non-physical realm (e.g. thoughts, souls, ghosts).

The conceptual interaction problem

However, Descartes’ student, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, raised the following problem for substance dualism in 1643:

“Given that the soul of a human being is only a thinking substance, how can it affect the bodily spirits, in order to bring about voluntary actions? The question arises because it seems that how a thing moves depends solely on (i) how much it is pushed, (ii) the manner in which it is pushed, or (iii) the surface-texture and shape of the thing that pushes it. The first two of those require contact between the two things, and the third requires that the causally active thing be extended. Your notion of the soul entirely excludes extension, and it appears to me that an immaterial thing can’t possibly touch anything else.”

In other words:

- Physical things only move when pushed by other physical things

- (for example, the ball rolls along the ground because your foot touches it with enough force to push it and make it move)

- But if substance dualism is correct, the mind is a non-physical thing and so the mind wouldn’t be able to ‘push’ or otherwise touch the physical body

- (the image I have in mind here would be getting punched in the face by a ghost: it wouldn’t hurt or feel like anything at all because the punch would just go straight through because the ghost isn’t a physical thing)

- And so if substance dualism is correct, the mind cannot move the body

- But the mind can move the body

- (for example, you can decide you want to raise your hand and you can do so using your mind)

- So substance dualism must be false.

Descartes’ initial reply

In Descartes’ reply to this objection, he points out that Princess Elisabeth’s claim that physical things only move when pushed isn’t quite accurate:

“Trying to understand weight, heat and the rest, we have applied to them sometimes notions that we have for knowing body and sometimes ones that we have for knowing the soul, depending on whether we were attributing to them something material or something immaterial. Take for example what happens when we suppose that weight is a ‘real quality’ about which we know nothing except that it has the power to move the body that has it toward the centre of the earth. How do we think that the weight of a rock moves the rock downwards? We don’t think that this happens through a real contact of one surface against another as though the weight was a hand pushing the rock downwards! But we have no difficulty in conceiving how it moves the body, nor how the weight and the rock are connected, because we find from our own inner experience that we already have a notion that provides just such a connection. But I believe we are misusing this notion when we apply it to weight—which, as I hope to show in my Physics, is not a thing distinct from the body that has it. For I believe that this notion was given to us for conceiving how the soul moves the body.”

In other words, Descartes’ rejects the premise of Princess Elisabeth’s argument (as stated above) that physical things only move when pushed: A rock falling through the air moves but it isn’t ‘pushed’ by anything.

However, this is really a minor detail as the general point – that physical things only move if some other physical thing (a push, the force of gravity, whatever) causes them to move – still stands.

We could adjust Princess Elisabeth’s argument and say something like the following:

- Physical things only move if some other physical thing exerts some physical force on it

- (for example, a push or the force of gravity)

- But if substance dualism is true, the mind isn’t a physical thing and so can’t exert such a force

- And so if substance dualism is correct, the mind can’t move the body

- But the mind can move the body

- So substance dualism must be false.

And so the problem re-emerges.

Descartes seems to be anticipate this response, as he continues:

“if I let myself think that what I have written so far will be entirely satisfactory to you I’ll be guilty of egotism.”

The pineal gland as the seat of the soul

Descartes’ later work, Passions of the Soul (dated 1649), was dedicated to the same Princess Elisabeth who raised this conceptual interaction problem.

And in this book Descartes provides a more direct explanation of how the non-physical soul could move the physical body. He says:

“Let us take it, then, that the soul’s principal seat is in the small gland located in the middle of the brain. From there it radiates out through the rest of the body by means of the animal spirits, the nerves, and even the blood, which can take on the impressions of the spirits and carry them through the arteries to all parts of the body. Remember what I said about our body’s machine: The nerve-fibres are distributed through the body in such a way that when the objects of the senses stir up various movements in different parts of the body, the fibres open the brain’s pores in various ways; which brings it about that the animal spirits contained in those cavities enter the muscles in various ways. That is how the spirits can move the parts of the body in all the different ways they can be moved. To this we can now add: The little gland that is the principal seat of the soul is suspended within the cavities containing these spirits, so that it can be moved by them in as many different ways as there are perceptible differences in the objects. But it can also be moved in various different ways by the soul, whose nature is such that it receives as many different impressions—i.e. has as many different perceptions—as there occur different movements in this gland. And, the other way around, the body’s machine is so constructed that just by this gland’s being moved in any way by the soul or by any other cause, it drives the surrounding spirits towards the pores of the brain, which direct them through the nerves to the muscles—which is how the gland makes them move the limbs.”

(By the way, the ‘small gland’ Descartes refers to here is now known as the pineal gland. And the pineal gland has been identified as spiritually significant by many different cultures, often regarded as a gateway to higher consciousness, the ‘third eye,’ or a bridge between the physical and spiritual realms. But that’s a story for another day)

Descartes also says:

“All that the soul actively does is this: it wills to do something x, and that brings it about that the little gland to which it is closely joined moves in the way needed to produce the doing of x.”

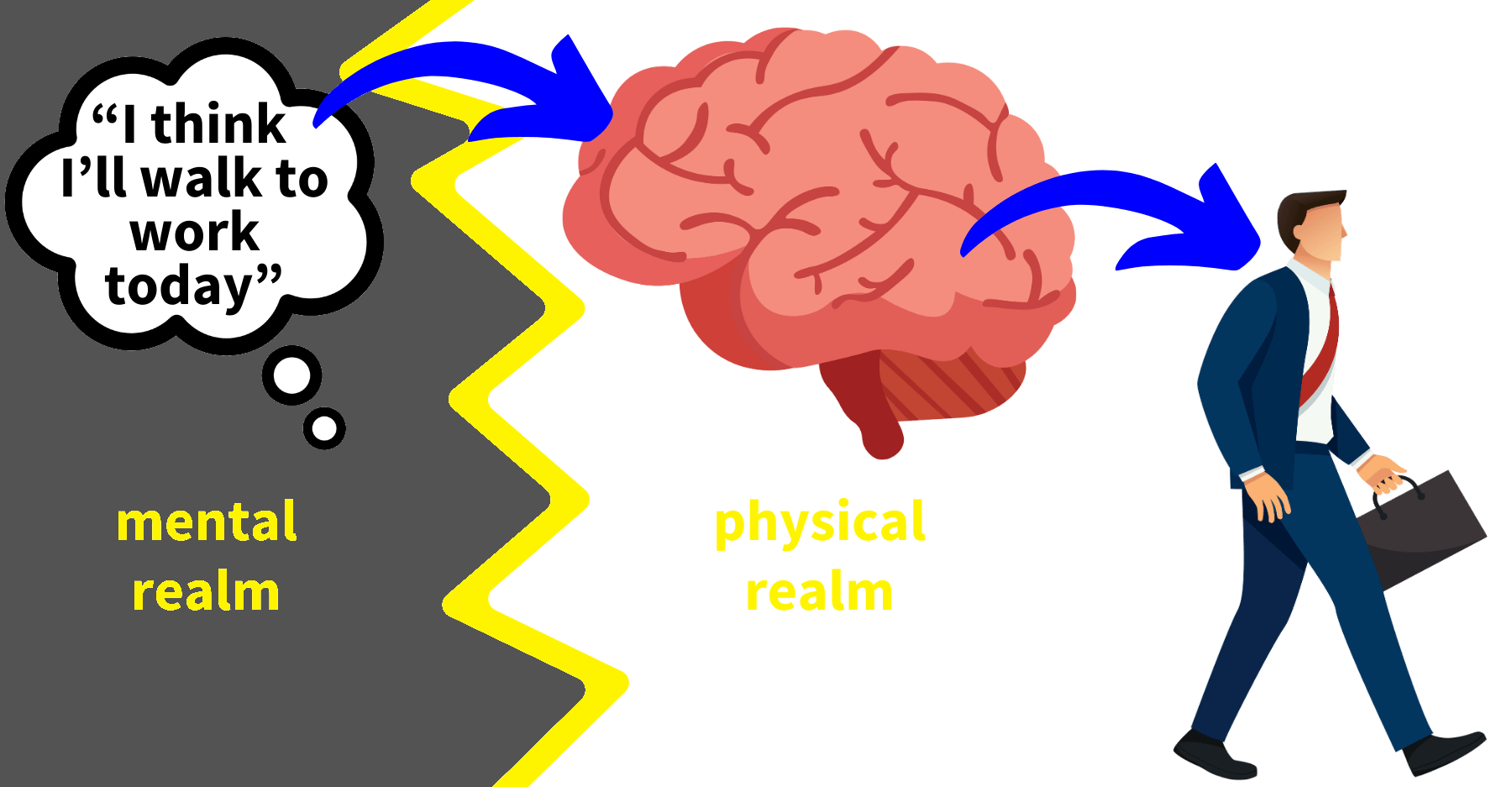

In other words:

- The soul ‘wills’ something

- (for example “I want to raise my hand”)

- This moves the pineal gland in the brain, which is kind of like an interface between the physical and non-physical realm

- And this movement radiates out through the rest of the body, causing movement

- (for example, my hand raises)

Summary

- Substance dualism says:

- The soul/mind is non-physical, and

- The body/brain is physical.

- But the conceptual interaction problem asks: But how could a non-physical soul/mind interact with and move a physical body?

- Descartes’ answer is that the non-physical soul interacts with the physical body via the pineal gland in the brain.

But does Descartes’ answer solve the problem? Or could we still ask how, exactly, the non-physical soul could vibrate, radiate, push, or otherwise interact with or influence the physical pineal gland?

The philosophy textbook written in plain English!

The philosophy textbook written in plain English!