The definition of knowledge is a big topic in epistemology and philosophy. The classic definition – which goes back to Plato in the 4th Century BC – was that knowledge is justified true belief. But this definition faced several criticisms in the modern era – particularly in the form of Gettier problems. In this post, we’ll look at Robert Nozick’s truth-tracking definition of knowledge, see how it avoids these Gettier problems, and also look at how it raises a new problem: The denial of epistemic closure.

Note: For A-level philosophy students, Nozick’s definition of knowledge is not specifically listed on the syllabus, but you could incorporate it into a 25 mark question on definitions of knowledge.

The truth-tracking definition

Robert Nozick introduced his truth-tracking definition of knowledge in his 1981 book Philosophical Explanations. Nozick’s approach shifts the focus to the relationship between belief and truth, emphasizing the importance of a belief being sensitive to the truth of a proposition – knowledge must “track the truth” across different possible scenarios.

Nozick’s 4 conditions for knowledge are as follows:

- S believes that P.

- P is true.

- If P were false, S would not believe that P (Sensitivity Condition).

- In nearby possible worlds where P is false, S would not believe that P. This ensures that the belief is sensitive to the truth.

- If P were true, S would believe that P (Adherence Condition).

- In nearby possible worlds where P is true, S would still believe that P. This ensures that the belief is adherent to the truth.

Example: The clock on the wall

To illustrate this definition of knowledge with an example: Imagine it is 3pm, you see a correctly working clock on the wall that says it is 3pm, and thus form the belief that “it is 3pm”. Would this belief count as knowledge according to Nozick’s definition?

To illustrate this definition of knowledge with an example: Imagine it is 3pm, you see a correctly working clock on the wall that says it is 3pm, and thus form the belief that “it is 3pm”. Would this belief count as knowledge according to Nozick’s definition?

- S believes that P.

- You do believe “it is 3pm”, so it satisfies this condition.

- P is true.

- The time is indeed 3pm, so your belief satisfies this condition too.

- If P were false, S would not believe that P.

- If it wasn’t 3pm – let’s say the time was 11am instead – then you wouldn’t believe “it is 3pm” because the clock would say 11am.

- This is what we mean by nearby possible worlds: It’s basically the same scenario as the one in which we form the belief, except the time is different. In other words, it is a possible world where the time is 11am instead of 3pm.

- And in this possible world where “it is 3pm” is false, you wouldn’t believe that “it is 3pm”, so the belief satisfies this condition too.

- This is what we mean by nearby possible worlds: It’s basically the same scenario as the one in which we form the belief, except the time is different. In other words, it is a possible world where the time is 11am instead of 3pm.

- If it wasn’t 3pm – let’s say the time was 11am instead – then you wouldn’t believe “it is 3pm” because the clock would say 11am.

- If P were true, S would believe that P.

- This is the scenario you’re in: “it is 3pm” is true, and you believe that “it is 3pm”. So the belief satisfies this condition too.

In this example, your belief that “it is 3pm” would count as knowledge because it satisfies all four conditions: belief, truth, sensitivity, and adherence.

How truth-tracking avoids Gettier problems

Gettier cases are situations where a belief is true and justified, yet still seems to fall short of being knowledge due to luck or coincidence. This suggests that the classic tripartite definition of knowledge – justified true belief – is not sufficient for knowledge.

For example, imagine the clock on the wall ran out of batteries in the night and stopped at 3am. In this scenario, you would still form the belief that “it is 3pm” when you looked at the clock, but this doesn’t seem to be knowledge because it’s just luck that the clock stopped at the right time. Your belief that “it is 3pm” is justified by the clock and also true, but it’s just lucky that the justification gives you the correct belief – if the clock stopped at a different time you would have formed a false belief instead.

For example, imagine the clock on the wall ran out of batteries in the night and stopped at 3am. In this scenario, you would still form the belief that “it is 3pm” when you looked at the clock, but this doesn’t seem to be knowledge because it’s just luck that the clock stopped at the right time. Your belief that “it is 3pm” is justified by the clock and also true, but it’s just lucky that the justification gives you the correct belief – if the clock stopped at a different time you would have formed a false belief instead.

The problem for the tripartite definition is that this belief is not knowledge, but the tripartite definition says it is knowledge (because it meets all 3 conditions).

However, by replacing the ‘justification’ condition of the tripartite definition with the sensitivity and adherence conditions, Nozick’s truth-tracking definition avoids this problem – it correctly says this belief is not knowledge because it fails to meet the sensitivity condition:

- Sensitivity Condition: If P were false, S would not believe that P

- If it were not 3pm (e.g., it was 2pm), you would still form the belief that “it is 3pm” based on this stopped clock.

- In other words, your belief is not sensitive to the truth: If “it is 3pm” were false, you would still form the same belief.

- So, your true belief that “it is 3pm” is not knowledge according to Nozick’s truth tracking definition of knowledge.

- In other words, your belief is not sensitive to the truth: If “it is 3pm” were false, you would still form the same belief.

- If it were not 3pm (e.g., it was 2pm), you would still form the belief that “it is 3pm” based on this stopped clock.

Just to emphasise the point again:

- The justified true belief definition says your belief “it is 3pm” would be knowledge, but this is wrong: It’s just lucky that the justification creates a true belief.

- However, Nozick’s truth-tracking definition says your belief “it is 3pm” does not count as knowledge, and this is correct: though the belief is true, the justification is irrelevant to the truth – it isn’t sensitive to the truth.

By requiring beliefs to track the truth through these additional conditions, Nozick’s theory filters out Gettier cases, ensuring that beliefs that qualify as knowledge are not just true by luck but are instead reliably connected to the truth.

Epistemic closure: A problem for the truth-tracking definition?

Epistemic closure is the principle that if a person knows a particular proposition (P) and also knows that P implies another proposition (Q), then the person also knows Q – that knowledge is “closed” under known implication. For example:

- You know that today is Monday (P).

- And you know that if today is Monday (P), then you have a philosophy lesson today (Q).

- Then, based on 1 and 2, you also know you have a philosophy lesson today (Q).

This inference seems reasonable: If you know 1 and 2, then you also know 3.

However, Nozick’s truth-tracking theory of knowledge denies epistemic closure: If you know 1 and 2, you don’t necessarily know 3, he says. The reason for this can be illustrated with brain in a vat and other philosophical scepticism scenarios:

- I know I have hands (P).

- According to Nozick’s truth-tracking definition, you do know you have hands:

- Belief: You believe you have hands.

- Truth: It is true you have hands.

- Sensitivity: If you didn’t have hands (e.g. you were in an accident and had to have your hands amputated), you wouldn’t believe you have hands.

- Adherence: If you did have hands, you would believe you have hands.

- According to Nozick’s truth-tracking definition, you do know you have hands:

- And if I know I have hands (P), then I also know I’m not a brain in a vat (Q).

- Because a brain in a vat doesn’t have hands – it’s just a brain in a vat.

- So, I know I’m not a brain in a vat (Q).

- This is implied by epistemic closure.

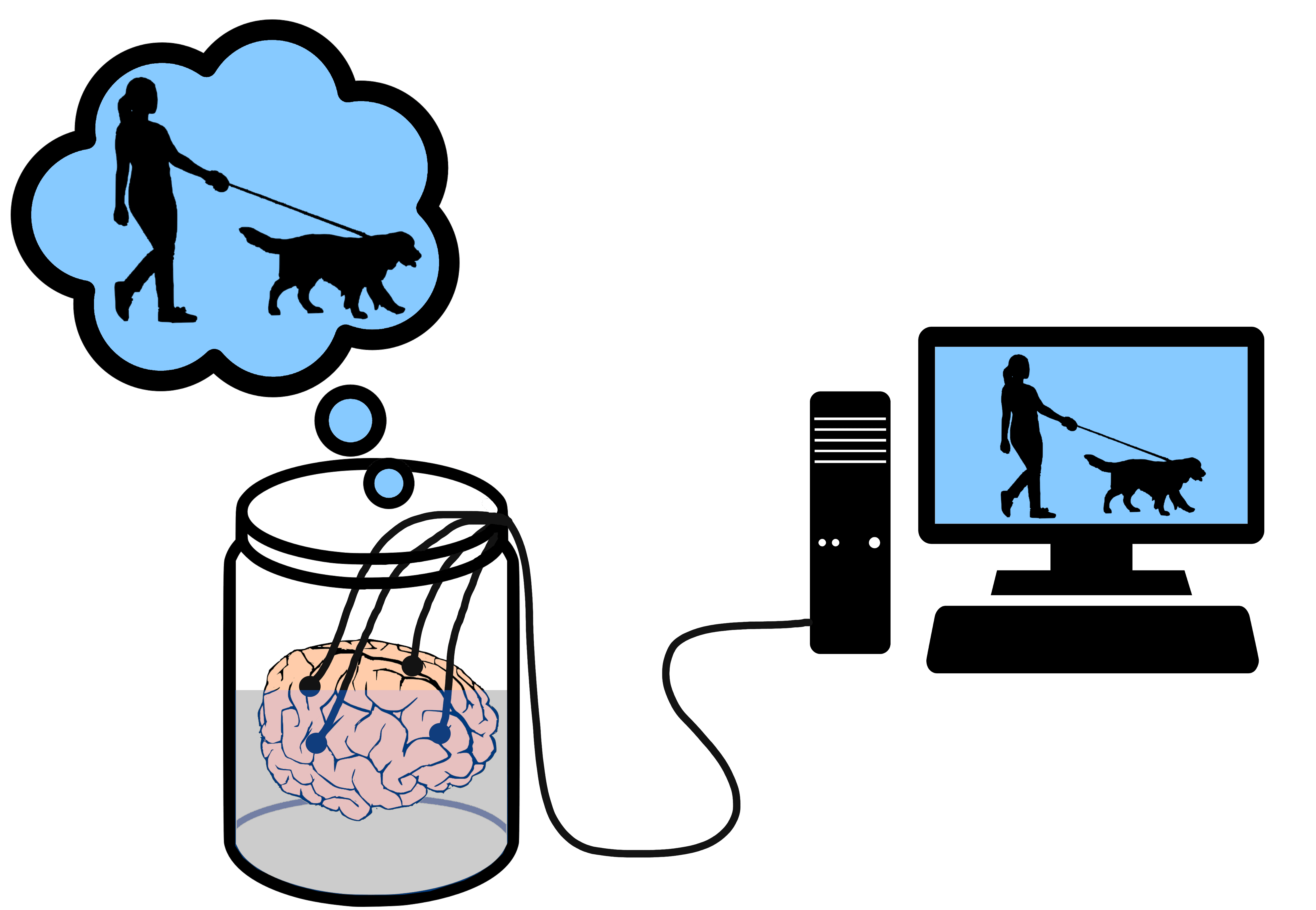

However, although 1 (“I know I have hands”) does count as knowledge according to Nozick’s truth-tracking definition of knowledge, 3 (“I know I’m not a brain in a vat”) would not count as knowledge because it fails to meet the sensitivity condition:

- Sensitivity Condition: If P were false, S would not believe that P

- If you were a brain in a vat and so your belief “I am not a brain in a vat” was false, you would still believe “I am not a brain in a vat” because the computer simulation would make you think this.

- In other words, your belief is not sensitive to the truth: If “I am not a brain in a vat” were false (i.e. you are a brain in a vat), you would still form the same belief that you are not a brain in a vat.

- If you were a brain in a vat and so your belief “I am not a brain in a vat” was false, you would still believe “I am not a brain in a vat” because the computer simulation would make you think this.

This breaks the closure principle as Nozick’s conditions require each belief to independently track the truth rather than relying on the logical implication from another belief.

So, if Nozick’s truth-tracking definition of knowledge is correct, then knowledge is not closed under known implication and so you can’t infer 3 from 1+2 above. This is potentially an issue, though, because many would insist that knowledge is closed. Again, to use an example, it seems highly counter-intuitive to deny that you can derive 3 from 1+2 below:

- I know my computer is not plugged in.

- And I know that if my computer is not plugged in, it won’t turn on.

- So I know that my computer won’t turn on.

Summary:

Robert Nozick’s truth-tracking definition of knowledge emphasises the importance of a belief’s sensitivity and adherence to the truth. This is done by considering nearby possible worlds: If the belief was false instead of true or vice versa, would the subject still form the same belief?

By incorporating these conditions, Nozick’s definition addresses the challenge posed by Gettier cases, ruling out situations where the truth of the belief is just lucky rather than because it was properly justified.

However, a consequence of accepting Nozick’s definition is that we must deny epistemic closure. Since sensitivity and adherence are context-dependent, we cannot rely on epistemic closure to deduce further knowledge from existing knowledge.

The philosophy textbook written with the student in mind!

The philosophy textbook written with the student in mind!